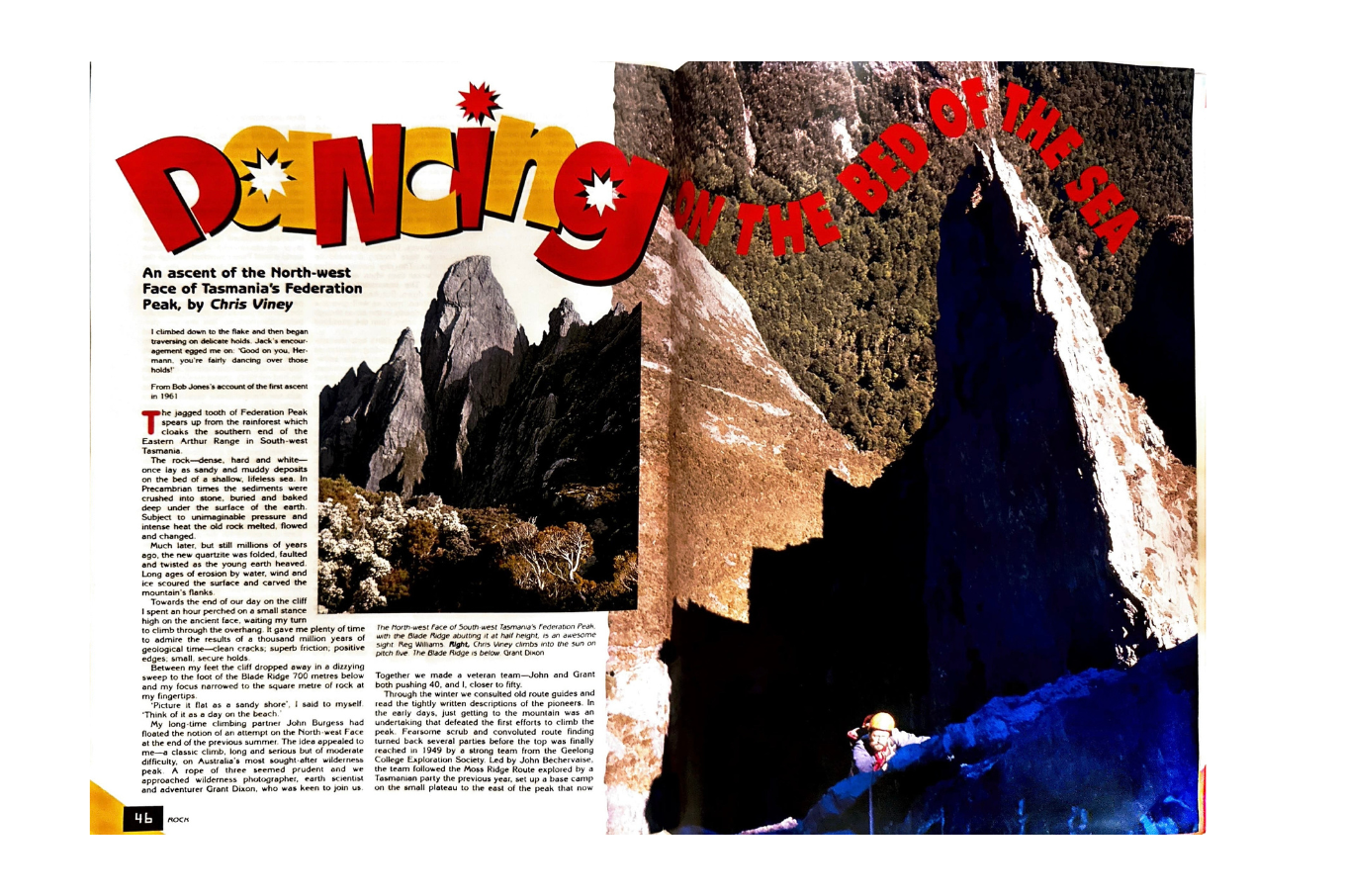

How Jared Anderson got his shot on "Storm from the East"

Words: Jared Anderson

Have you ever chundered on your hero? No? Well nor has Jared. But he’s gotten a lot closer than most. The Bluies-based photographer is generally pretty confident about setting up shoots—navigating loose rock, long approaches and reading routes in reverse as he raps down with a sackful of photography gear. But the day after a big night, abseiling in from above to photograph Tim Macartney-Snape, he found himself afraid of dislodging more than loose rock.

On behalf of all climbing photographers around the world, I’d like to tell you: a photo from a multi-pitch route is often much more involved to capture than it looks. Not crazy difficult, just harder than you would expect from just seeing the end result.

That’s certainly not a complaint, quite the opposite. Climbing 10 grades under your limit becomes boring quickly, just like photographing routes that provide no challenge also lose their appeal.

For most of my shoots in the Blue Mountains there are medium to long approaches, heavy loads of static rope and gear to carry, tricky abseils and long jumars back up. Most climbers who know the area would expect this level of effort when they see the photos.

What’s often not visible is the loose rappels with dirt, scree, shrubs and large rocks interfering with my descent. The conditions in the Blue Mountains means that when I’m a few metres right or left of the climbing line, I become the first human to have touched that rock. And there are plenty of rocks that don’t like to be touched; they protest by breaking off and plummeting to the ground, far below.

For every loose rock, I have to consider the safety of anyone beneath me, as well as my own safety once I get lower. For every sharp edge, I have to consider whether to protect with a rope-pro, a cam, a less than ideal nearby shrub, or to not protect at all. It’s not overly difficult, but it’s not easy either.

I must consider the changing lighting conditions and my camera settings, the climbers’ progress through the pitches, the angle, and artistic vision I want to capture. I also have to tuck my body so my rope bag, shoes or straps are not accidentally getting in the shot.

Again, it’s not that difficult, but it’s not easy either.

For most popular routes there is clear guidance both in the guidebook and online about exactly what gear to pack and what to expect on the route…but only if you’re climbing it.

If you’re photographing it, descending from above, you’re doing it in reverse. You need to repurpose the guidance as best you can by using the climbing beta and make your best guesses for all the remaining information gaps.

Popular sport crags can sometimes be more straightforward, but on longer or more remote routes there are often plenty of questions that can only be answered once you’re out there on the rock. I’d much rather have a heavy pack and a longer jumar ahead knowing I’m in exactly the right position, than a light pack but unsure if I should rap right or left of an arete—the wrong answer could ruin the whole shoot.

The process is technically not difficult, but it can still be stressful at times. So when I lined up a photoshoot with Tim Macartney-Snape in an area I knew reasonably well with good information, I didn’t think it would be especially difficult. While I didn’t expect a total walk in the park, I just thought that things wouldn’t get too complicated.

I’d been wanting to photograph Tim for about 12 months. We were both keen but we could never get our schedules to align. Tim is my mountaineering hero, so to say I was excited when we finally locked in a date and route, would be an understatement.

The weekend plans were: simple photoshoot with friends at Shipley (a Blue Mountains sport crag) on Saturday, a birthday party with campfire, drinks and camping that evening, followed by the “Storm from the East” photoshoot on Sunday with Tim. So how difficult could that be…?

Let’s just say “near death” or “like a bag full of arseholes” are both fine ways to describe how I felt waking up that fateful Sunday morning. The beers I had enjoyed the night before were having their revenge.

Tim and I did the meet and greet, located the rap in point and I bounced down the rappel, swinging side-to-side with my two ropes, randomly half-twisting back and forth like a washing machine as I tried to get my desired mid-air position; all whilst trying to keep my stomach contents still inside my stomach.

Did I mention that Tim was directly below me at this stage? Have you ever met one of your heros and had a serious think about whether you might actually spew on them?

Not just spew in their presence, not just a splash on their shoes, but a large quantity of spew landing on them from 30 feet above, like raining spew, ON A LIVING LEGEND.

I’ve dealt with plenty of photoshoot challenges before, but I’d never expected this kind of problem. Tim and his climbing partner, the poor buggers, were lashed to a hanging belay so they couldn’t even resort to the 5 D’s of dodgeball to escape –dodge, duck, dip, dive or dodge..

It’s good etiquette to yell “ROCK” if you dislodge something from above, but do you actually yell “VOM” if it becomes a risk? What the hell is the protocol for this situation? If you were in their climbing shoes at this moment, would you appreciate the heads-up, only to wish you hadn’t actually turned your head up? Or would you prefer it to be a confusing, yet slightly warm surprise?

After my belly stopped churning, I was beyond thrilled to see the route was so overhung that there was no chance my personal “Yak Banquet”* would reach them. As a bonus, I didn’t even have to chunder into my camera bag.

Climbers often admit that epics and ordeals make the best campfire stories. After this adventure, I can tell you it is probably also true for photographers.

*“Yak Banquet” is also the name of a grade 22 multi-pitch in the Blue Mountains. Unlike what Jared was afraid of unleashing, the climb has a three star rating.