Seven years on Hump Of Trouble

Words: Tom O’Halloran

Images: Brecon Littleford, Kamil Sustiak

When professional climber and australian olympian tom o’halloran bolted a 10-metre sport climb in a dark cave he didn’t realise it would become a years-long obsession. He takes us through the journey—physical and emotional—that led him to send what may be australia’s hardest route.

In 2008 I wrote a message to a friend, who had just completed a mega long-term climbing project. I said how inspired I was and that one day I wanted to find my own mega project that could beat me up, throw me around and I could really sink my teeth into.

Sitting there writing the message on the school library computer, I pictured this beautiful flow to the struggle: pushing through the tough stuff with purpose and grit and a smile. However, a decade later, swinging around on the end of a rope four meters above the ground, in a dark, cold cave, screaming f-bombs at the top of my lungs, up to my neck in the reality of pushing my limits, I wasn’t so sure.

Like many challenges in life, at least in my experience, I didn’t really know what I was signing up for with this project. When I bolted it in 2015, it looked hard, sure, but everything I bolted always did. Most projects I’d then spend a few days or a season on and they’d be done. Why would this be any different?

Walking into the crag for the first day of my third season in 2019–let’s call it about day 41–I realised that the “Hump of Trouble Project” may be a little different to the ones before.

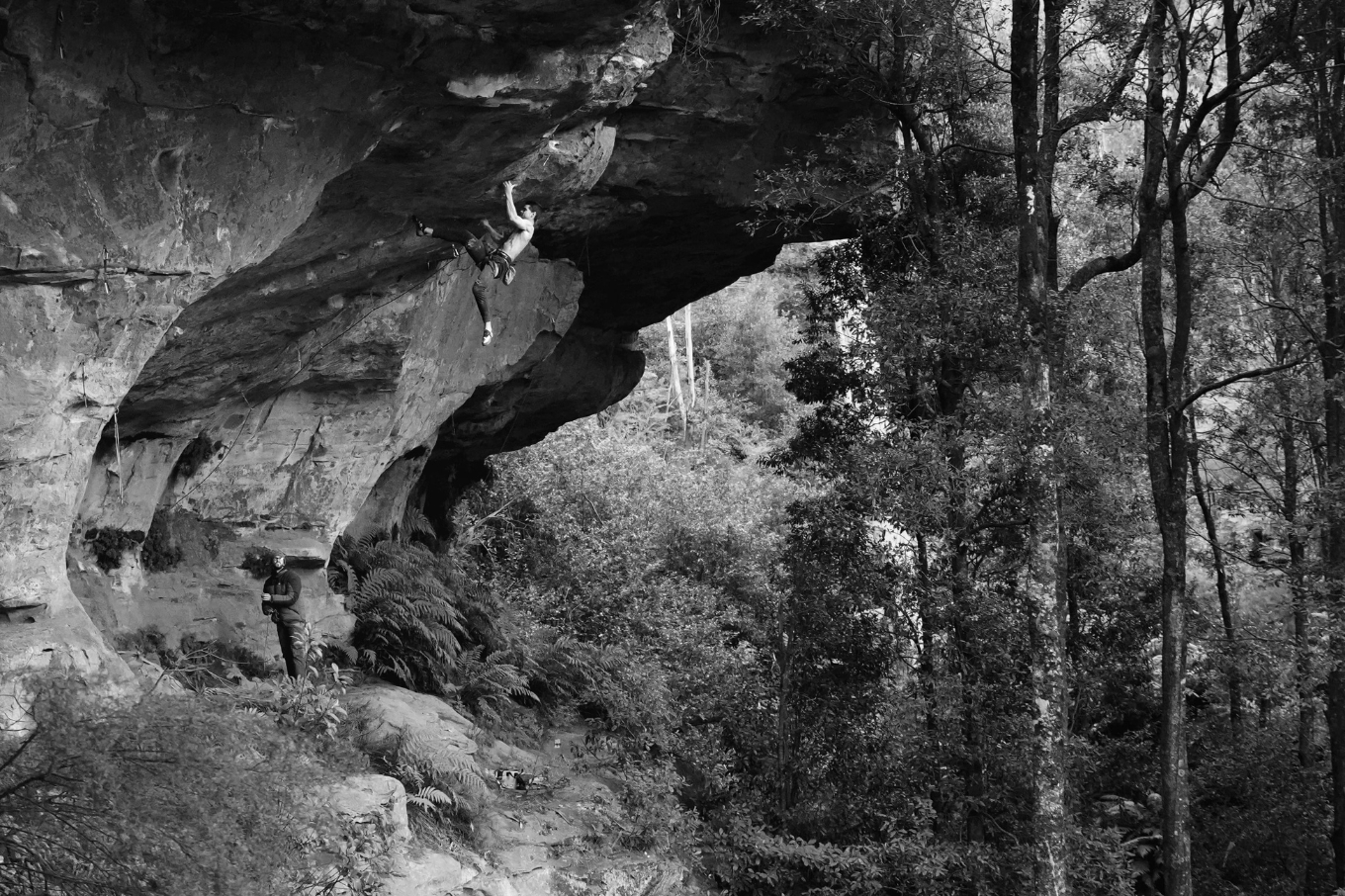

It’s a very “un-Blue Mountainsy” climb. Not a glorious line on a slightly overhung orange face, dappled in sunset light. It’s a very short little zigzag line through very steep, grey rock, in the middle of a dark cave. It held a different beauty.

In the beginning I’d taken about 20 days to whittle the route down to 15 moves that felt like a sniff at a redpoint-able sequence. Fifteen of the most intense and consistent moves I’d ever tried on rock. I loved it.

The 2017 and 2018 seasons, the first two, I really enjoyed. It may sound absurd, but dangling about, trying to unlock the puzzle to climb those 15 moves without falling off never felt like a chore. I had mini goals for each day and was always psyched to show up and just keep chipping away. I’d find a win in the smallest thing, and it’d fuel the hunger to return. Every little bit was one step closer.

In 2019, however, the whole thing started to unravel. I’d been sharing small parts of the process on social media and enjoyed showing people what it was all about. But as the days I’d spent on this started to add up, talk started to happen around how hard this route could be.

Could it be the hardest route in the country? Could it be the next grade jump in Australia? What would that mean? What could it mean globally? Would it be something that could tempt Adam Ondra down? Would he be able to onsight it? Would that mean, after all this effort, that I’m weak?

With all this crap floating around in my head I was completely paralysed while climbing. This sucked even more because I’d put in some solid training coming into the season and really felt like this could be the year. Now, feeling the best I ever had physically, my head was kicking hard against me—not something I had ever previously experienced. I desperately tried to find a way through the noise, but would always leave the crag more confused and frustrated. All I could think to do was to keep showing up, day after day.

By now I was falling off the second last move. A jump to a left hand slot, where you’d then cut loose, swing the right foot back on and jump for the victory jug. I was falling there twice a day for days and days. It could go any day now! But it didn’t.

Could it be the hardest route in the country? could it be the next grade jump in australia? what would that mean?

The pressure of that, piled on top of all the other head noise, drove me even more insane. Each time I fell from the jump, or any lower, I’d scream and swear and throw a tantrum. I was so frustrated and angry and lost as to what I needed, to finally just climb. I struggled to tap into the Tom I knew was there, who could just pull on and enjoy moving across rock, finding the balance between intention and flow and hunger and peace.

Anyone who’s been here knows it’s not as simple as just relaxing. “Just breathe through it and chill” was not something I could do here. I was desperate to climb it and to have all the glory I thought lay on the other side. Somehow, one day, I found a moment on the wall where the noise cleared, and I just climbed. I felt floaty and free. Moving up the wall without conscious effort. It was just happening.

Then I was jumping for the left-hand slot, where I’d fallen 10 plus times already, and I stuck it. Suddenly all the floodgates of head noise were back open, and my mind exploded: “This is it Tom, you are finally going to climb this thing. The hardest route in Australia. You’ve never fallen on this move, ever. This whole journey is over. Let’s take it to the top!”

This, of course, made me completely rush the move and I threw myself totally out from the wall. I got my hand wrapped around the finish hold, but the momentum I had heading in the opposite direction meant I just couldn’t hold on. Now I’m swinging around on the end of the rope, screaming myself hoarse, knowing I’d totally choked. That wasn’t how it was meant to go.

I went back for a few more days, but they weren’t productive. Now with the pressure of really knowing it could happen, I was even more stuck. I just couldn’t find the flow again, stuck in the cycle of noise and nonsense. It had been about 60 days and the grind of showing up over and over was taking its toll on me. I was turning myself inside and out, looking for the solution. This is what it’s like to be in the dark abyss of redpointing.

This is what it feels like to be pushing your limits, completely consumed by one silly piece of climbing that means everything. This is not what I had in mind in the library when I sent that message. This is way more uncomfortable.

Having said that, I never doubted I would eventually do it. For whatever reason, I knew from day one, I was going to climb this thing. The impatience of when it was going to happen was my undoing. I felt like I’d done everything I’d been asked and it still wasn’t happening. This was what was driving me crazy. “What more do you need me to do?”

Soon enough the season shut down and that was it. The bitterness and hunger of the fall, still in my mouth. I knew I could do it and would be back for 2020.

That next season I injured myself a few times before I could even make a start on the route. It really hurt to sit at home, knowing the route was there waiting and I just couldn’t pull on. But I’d make it happen in 2021.

That didn’t happen though, as I ended up qualifying for the Olympics.

A side project I had been working on alongside my outdoor climbing goals. It was a total dream come true to walk out onto the Olympic stage, wearing the Green and Gold, showcasing Sport Climbing to the Olympic world for the first time.

Coming home from Tokyo, I was burnt out and needed a rest. Despite being in the best shape of my life and the season still being on, the thought of trying hard and going through the redpoint whirlpool made me want to curl into a ball and cry. I was spent. Next year would be the one.

Again, that wasn’t to be. Twenty twenty-two did nothing but rain. Totally saturating the cliff and making it more like a water park than a climbing crag. By now I’d spent as much time trying the route as I had off it. A bit of a strange feeling really. The more time went on, the more I built the route up in my head. The story I told myself and the pressure I felt after falling from the last move, grew. I was building a monster nightmare in my head.

Eventually pulling back on in 2023, was nothing like I expected. It felt incredible. Incredible to be back down there, playing in my own little world again, remembering the subtleties and quirks and feeling of the moves and holds. I’d worried and stressed that maybe the time had passed and I’d never be back here, never climb past the jump, never be able to lay this one to rest. But even walking back into the cliff, looking up at the line, I knew it was going to happen.

This is what it’s like to be in the dark abyss of redpointing. this is what it feels like to be pushing your lim- its, completely consumed by one silly piece of climbing that means everything.

It took nine days to get back into the full groove of the route again. The first few days were only dabble days while climbing other lines at the crag. I’ve always liked the “soft opening” to a hard project season. If I have a big project at a cliff, I’ll find a second-tier project to knock over early and hit the big one with momentum. There’s just something nice about knowing you’ve been to the top of the cliff on redpoint already. You know how the party works.

On day nine, I was feeling incredible. I’d had a warmup at home and headed down to the cliff feeling light in my heart and head. I’d found a space where I was just feeling really happy to be out climbing, and to be able to put my energy into something special and meaningful.

My bolt to bolt warm up felt crazy. Like someone had made the holds twice as big and turned gravity down by half. I felt like I had all the time in the world on the holds and could play with it how I wanted. This was cool!

Redpoint tie in one for the day felt just as good and suddenly I was jumping for the slot move again. A move I hadn’t got to from the ground for four years. I fumbled the hold and landed on the end of the rope. But instead of the usual dummy spit of years gone by, I was psyched. I was back here, feeling good and was totally happy to just stay the course.

Tie in number two went the same. I jumped for the slot, fumbled, and landed on the end of the rope. Again, smiling. This was awesome. This was me.

This was the place I needed to be in to get the best out of myself. A feeling of peace and contentment, sprinkled with a healthy does of frothing hunger to send. The place I had been searching for for all those previous years. A true acceptance that all I needed to do was keep putting in the work, keep showing up and keep giving it everything I had. To relax and enjoy the ride.

Tie in number three, I had decided to commit to bloodshed. The right hand hold you use to jump for the slot move is sharp, and had taken a health tax on my finger’s skin many times before. I had a few options available to get through this attempt. Taping the finger (resulting in less good friction on the crucial hold), using a different grip position (suboptimal pulling power), or go all out, use the strongest two fingers and gamble completely tearing open my finger, giving myself a wound that could take weeks to recover, but giving myself the best possible chance of sending. But if I didn’t send, were the consequences going to be worth it?

I was here to do it though, not avoid it. Let’s give it everything.

My bolt to bolt warm up felt crazy. like someone had made the holds twice as big and turned gravity down by half.

As I lined up for the jump, I felt the skin on my finger tear. But suddenly my left-hand fingers were sunk into the little slot and I was still on the wall. My feet swung out and as I planted them back on the wall. I concentrated hard. Consciously taking a moment to pause and set myself up to do the move properly. I wasn’t going to stuff this one up again.

I threw and hit the final hold, letting out a huge scream. It was over! Well, kind of over. The hard bit at least. I clipped the last draw and only had two body lengths of grade 15 climbing to the anchor. As I pulled up through the dinner plate jugs, my stress levels went through the roof at the thought of one of these holds breaking off. I’d had nightmares about this for years and now I was face to face with them. Imagine after seven years, if I finally stick that move, only to have a hold break on me. I wouldn’t know what to do.

Thankfully, the rock gods were smiling on me, and I clipped the anchors, sank into the rope, and felt it all. It was finally done. A piece of climbing that had beaten me up, thrown me around and taught me a whole lot. I think we really only get one experience like this in our climbing lives, if we are open to it. One journey through the rough and bumps and hope we make it out the other side. This is a special one for me, but also an experience I won’t be signing up for again too soon. Haha.

Thank you rock climbing. Thank you, Hump of Trouble. You’re the best.

The incredible Rose Weller sending iconic Nowra line, White Ladder (33). Image by Michael Blowers.