Look out below! Rogue waves and sea cliffs.

Words: Mat Young

Climbing safety is everyone’s responsibility, and it’s something our editorial team are incredibly passionate about. Our Tale of Whoa column is our continued commitment to creating a culture of safety within our community. This edition we welcome guest contributor Mat Young, who was swamped by a series of freak waves as he climbed on Bruny Island’s sea cliffs.

Giant walls of water engulfed us again and again. They hit so violently that I could taste the brine as it was forced into my mouth and up my nose. In the swirling chaos I caught flashes of blue and white and darkness, as I bounced against the rock face, tangled in the rope.

Amid the maelstrom, I experienced a moment of stillness and clarity as I thought to myself,

“If any part of this system breaks, we’re dead.”

Stories about climbing epics are usually fairly similar, they go something like this: We went here, we bit off more than we could chew, then we got hurt or lost.

Well, this story isn’t like that. On a weekend climbing trip to Tasmania’s Bruny Island, the Southern Ocean taught my friend and I a valuable lesson. We were climbing on the sea cliffs at a crag called World’s End when a series of rogue waves hit us hard. Our exposed position meant it almost ended in disaster. The irony of this is not lost on me.

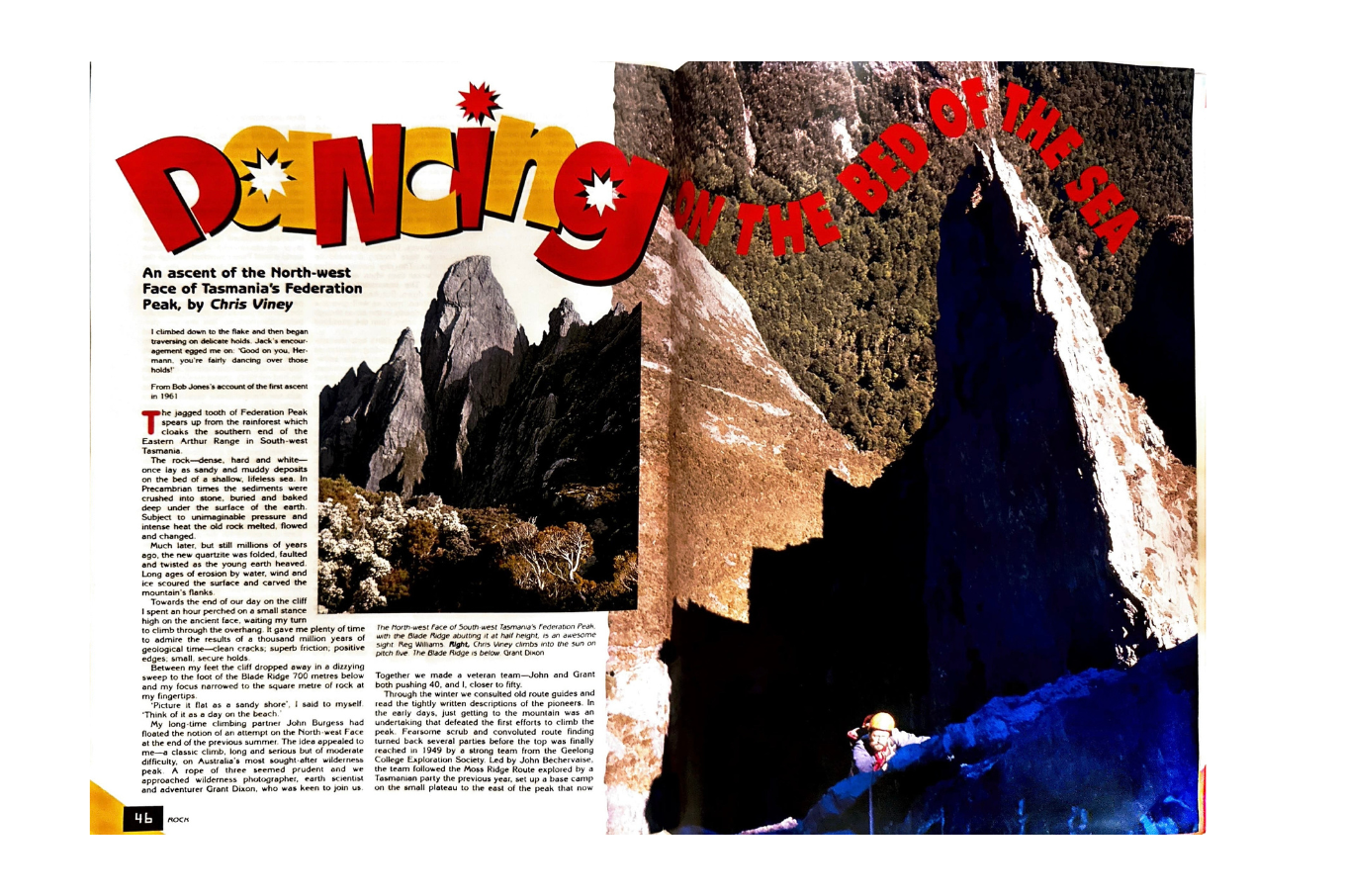

The southern end of Bruny Island holds a series of highly featured dolerite cliffs that have been shaped by the constant beating of huge Southern Ocean swells. These cliffs, which have been developed by local climbers, contain a high concentration of quality sport climbing. This was what my buddy Rick and I had come to sample. On this trip, the weather was grey and windy, and the cacophonous crashing of waves gave the climbing an intensity that I have never experienced before.

World’s End was where we chose to climb our first pitches of the trip. Located on a narrow spit of land with routes about 20m high and a convenient slab at the bottom. When we arrived, everything was dry and clean. While we set up our rappel, and during our first few climbs, we kept a wary eye on the sea below us—the turbulent, foaming mass had a threatening presence and I knew from experience the Southern Ocean can be dangerous. Despite that, not even a splash reached us during the first 90 minutes or so that we spent climbing. Confident that the water was benign, we shifted our focus solely to the rock.

It was late morning, and having each led a couple of routes to warm up, we moved on to some of the harder climbing on the left-hand side of the cliff. Balanced between the third and fourth bolts with delicate, thoughtful climbing, I was in the zone. My focus was narrow, nothing else mattered.

Suddenly, I was torn from this flow state by Rick screaming, “OH F***!”

I looked down in time to see him engulfed by a wall of whitewater which continued to rise and rise. All I could think was “Hold on!” as I desperately tried to cling to the wall. But it was no use. The churning water rose until it ripped me off the cliff.

When the sea receded, Rick and I looked at each other. “Holy shit!” we chuckled, adrenalin pumping.

“Better lower me off mate,” I said.

But the receding water had taken the other end of the rope, tangling it in kelp. We were stuck. That’s when I noticed that the swell was building again.

Something I’ve noticed before is that I’m always strangely detached in these kinds of situations. I don’t panic, I don’t even really get scared. Instead, I get focussed.

While tumbling around completely out of control in the washing machine created by tons of water, the thought occurred to me in real time: “Man, if any part of this system breaks, we’re dead.” I gripped the rope a little tighter.

We were smashed into the cliff by three more giant waves before the final wave was sucked back out into the ocean. Rick and I knew straight away that we needed to move, and move fast.

“Get me off the wall NOW, man!” I urged Rick.

The rope was still stuck and I was still hanging, helpless, five metres up the wall. Eventually, we worked the rope loose and freed ourselves from the system, taking care to remain anchored to the wall at all times in case another set came through.

Dissecting this incident in order to learn from it I have concluded that Rick and I didn’t do anything wrong this day, except for maybe not showing the ocean enough respect. Rogue waves like this are responsible for 13 deaths per year among fishermen, and we climbers are just as vulnerable in situations like this.

Water hazards are not something climbers would generally be aware of, or even think about for that matter, but they are potentially deadly. Checking the swell height on a website like Willy Weather may have given us some clue as to the likelihood of a rogue wave being high enough to reach us. But we never even considered that—big swells are common in the area, but I’d never heard of anything that caused issues for climbers.

So how else could we mitigate against this risk? One way would be to keep an end of your rope tethered like a handrail to the cliff, which will allow you to move about while secured to it. This small action will reduce the likelihood of someone being swept away in a similar incident.

Rick and I are both experienced and safe climbers, yet, on this occasion we were caught off guard by the unpredictability of Mother Nature. We survived because of luck and chance. It’s a lesson for us all and hopefully we don’t have to rely on luck in the future. Safe climbing!