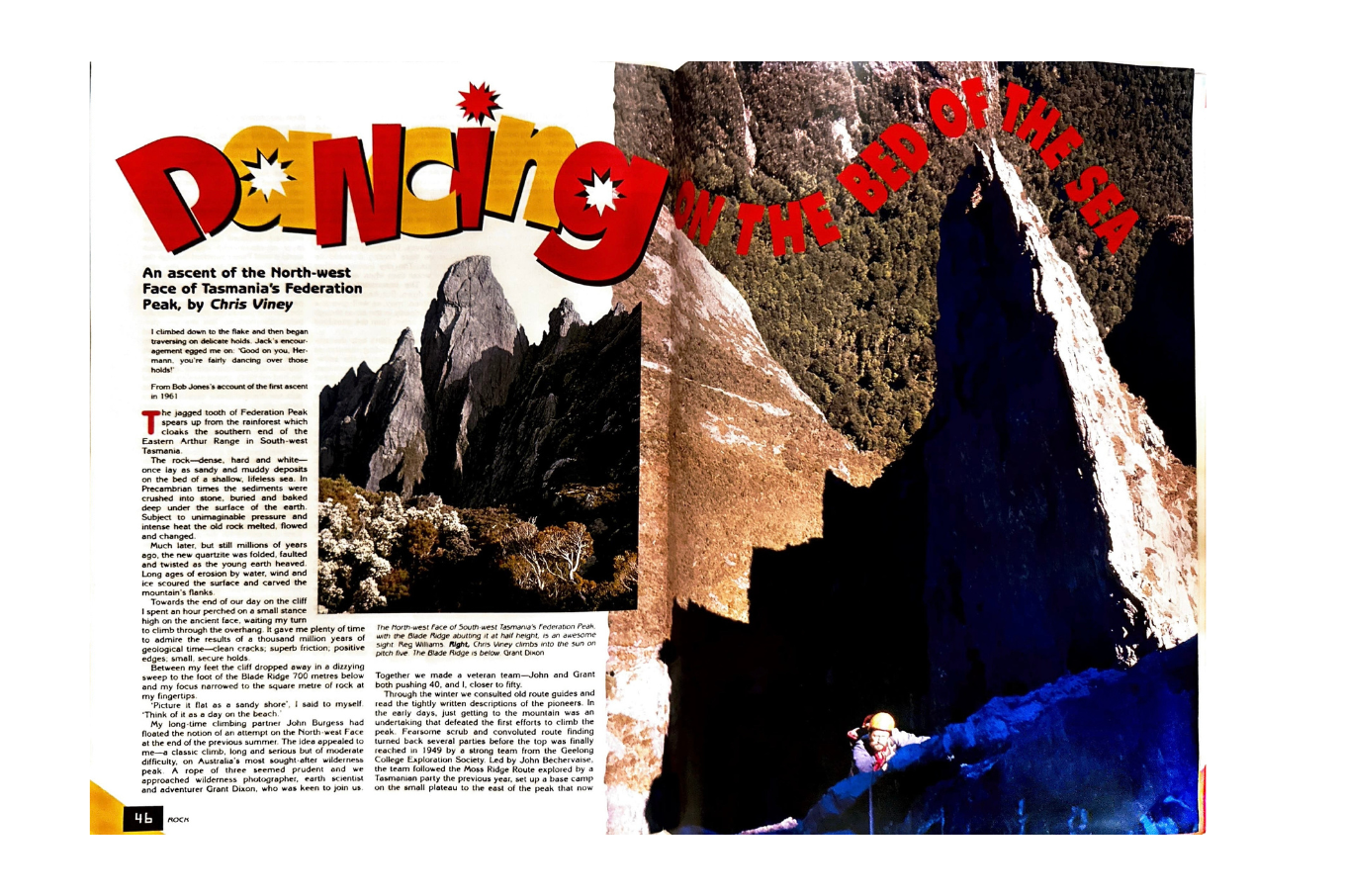

Getting to know rock climber Doug McConnell

Images by: Kamil Sustiak Of Doug On The Valkyrie (8c/33), Hanshelleran Cave, Flatanger, Norway

Doug started climbing in tassie a quarter of a century ago and has dabbled in trad and bouldering, but is now focused on redpointing hard sport routes. Two years ago, he moved to spain with his partner, kerrin, for the glamour of living in a car in the sport climbing centre of the world. He is proudly supported by La Sportiva.

You’ve been living in Europe for two years now—what do they have that we don’t in Australia?!

It’s hard to sum up succinctly how different it is here. Spain is the undisputed sport climbing capital of the world. There are more hard routes in Spain than in France and Italy combined. Both the rock and the climate lend itself to hard climbing, and this brings the best climbers. The culture is amazing—I love that I can go to crags like Santa Linyaor Rodellar and climb, shoulder to shoulder, with some of the best in the world.

The sharing of knowledge, ideas and psych really makes the environment conducive to hard climbing. Grades somehow have a different gravitas when you see someone flashing your project – suddenly it seems a little more attainable!

What I believe happens is that because there are so many great climbers, there is always someone better than you—even if you climb 9b+[38 in Australian grades]—so people are usually very humble and encouraging towards each other. It’s as though there’s a common goal of working together to push the limits. I love this environment. It’s what I imagine it would be like for a marathon runner to go to the Rift Valley and run with the Kenyans.

And what about the rock itself?

Aside from the culture, the rock is really different to Australia. I especially love the big limestone caves. In the last two years I’ve climbed mostly in these, seeking out the biggest steepest most audacious looking routes I can climb on. I enjoy the whole body physicality of these routes—I’ve spent up to 45 minutes redpointing a single pitch! Suffice to say this is quite a different experience to crimping in Centennial Glen (Blue Mountains).

I find that in Australia, for the most part the climbing is reduced to the strength of what’s below your elbows. Obviously, this plays a role in the caves, but the steeper and more featured it gets, the more you get to use your whole body.

The result is I can climb more, because I’m less limited by skin damage to the last joint of my fingers and I’m often getting a training stimulus from just climbing on rock. Being more 3D climbing, there are lots of tricks to these routes, which means that there are often lots of different ways to do sections and lots of routes that don’t just depend on your ability to do one specific move.

Another thing that’s great about being here is that there are lots of others doing what I am—living in a car and going climbing as much as possible. There are not many places in the world where the climate and the amount of rock allows this lifestyle year-round.

I love this environment. It’s what I imagine it would be like for a marathon runner to go to the rift valley and run with the kenyans.

What do you miss about climbing in Australia?

I miss being able to go to the crag with friends. The banter is never the same across the language barrier—especially if the other’s language is American or British.

I miss those crisp winter (or summer!) days in Blackheath when the snow clouds are just out of reach and westerly winds turn the rock to velcro. I miss good coffee, my training room, exploring and developing the Bluies and expensive beer (wait, not that one).

And how did you get into climbing in the first place?

Dad used to take us bushwalking as kids. I found it boring but always wanted to go up things – trees, rocks, etc. Then as a teenager I saw some sort of extreme sport compilation at an IMAX cinema…I can still picture an image of some cheesy dude in fluro and sunnies cruising an American sandstone splitter. I thought that was somehow the coolest thing I’d ever seen.

A few years later I moved to Tassie to play cricket and started dabbling with climbing. Within months I gave away cricket. I never fully got into fluro.

What made you want to focus on sport climbing?

Part of the culture in Tassie when I started climbing was to look down on sport climbing—the real hard men of climbing were completely dismissive of it. I spent a lot of time doing chossy and scary trad, and talking shit about lame sport climbing scaredy cats. But I always wanted to be better. It took me years to realise that the climbers that were better were not just gifted that ability, they had actually worked for it—and the obvious continuation was the realisation that I too could do something to change my ability.

I was slow to catch on, but a year mostly sport climbing in Europe in 2009/10 had me hooked. Since then, I’ve still dabbled with bits and pieces of trad, and even the odd boulder, but the focus now is sport climbing…before I’m too old to improve.

Tell us about a route you felt you grew as a climber on?

Last year I climbed Coma Sant Pere in Margalef. This probably ranks as my most frustrating redpoint experience, but also the one that I’ve learnt the most from.

It’s a 50ish-metre pitch up the imposing, 45-degree-overhung, Visera wall. This one was a saga and, at times, I was completely sure that I wouldn’t do the route and that I would walk away having climbed very high, very often. This was the route I’ve spent the most time on in the last two years. It took me to some dark places mentally.

On my eighth day of climbing on it, I fell above the last bolt (of 17). I proceeded to fall there, on relatively easy climbing, for the next 11 climbing days. It doesn’t sound that bad in retrospect, but this took over a month of effort. I was climbing mostly day on, day off and only climbing on that one route.

Because of the size of the route, I would only have one good go in me per day, which compounded the mental pressure to make each go count. In the end we even left Margalef (I left the ‘draws on) and went to Santa Linya for a change of scenery, because always falling in the same place, after 30 odd minutes on route, was breaking my brain.

Finally, on day 20, after mentally throwing in the towel, but still having to go to the top to get the ‘draws off, I eked out those last few moves. After confirming with Kerrin (on belay) that I hadn’t weighted the rope, the overriding feelings were of confusion and relief.

Any tips for projecting routes?

So many. But one thing I think trumps any more specific tactic is to be conscious of what you’re actually doing, so that you’re ready for when it gets hard mentally. Simply put, I think the key to projecting is acknowledging the risk vs reward ratio and accepting that the more risk, the greater the reward. But also the greater the risk of coming away empty handed.

The best projects are those that force us to change. A project should keep you awake at night, it should make you nervous thinking about it, and it should certainly not have a known outcome.

Embracing discomfort: Projecting should not feel comfortable. Its confronting and challenging and really quite uncomfortable for most of, if not the whole, process.

Impossible to possible: I think the sweet spot for a project is when you don’t know if you can do it. If something is possible but not probable, then any and all progress is rewarding. The cliché of taking something that’s impossible, to being possible, is a cliché because it’s real. And it’s a beautiful thing when it works.

Getting it wrong is getting it right: Once you’ve been through a few projects, you know that something that feels impossible on the first day (or even the first five days) can quickly change into feeling close to completion. So, finding a project that’s at the right level—one that really makes you question your choice, but that ultimately becomes an engrossing challenge—is not easy. You will (and should) climb on projects that you don’t do…or not without stepping away and coming back better anyway.

No, that other sort of fun: The best projects are those that force us to change. A project should keep you awake at night, it should make you nervous thinking about it, and it should certainly not have a known outcome. I think if you can sign up to this concept from the outset, you will be more able to deal with the tough times when they (inevitably) arrive.

What are your next goals?

I actually don’t like talking openly about goals or what I’m going to do because it’s been shown to reduce the likelihood of actually doing it. That said, I’m really motivated to keep pushing my level in sport climbing at least for the next couple of years.

For this year there are two routes in particular that I’m keen to put time into. I’ve climbed on both of them previously and doing either of them would represent a new level for my climbing.

Anything final words of wisdom?

I’ve been conscious lately that my relationship with climbing has changed a lot over the years. I remember my first climb on the Organ Pipes above Hobart and how mind blowing just being up high was. Now it’s all about difficulty for me—something my younger self would have scoffed at.

My climbing practice has been really disjointed, I’ve had large periods off due to study, injury, work, cricket, but I’ve been consistent. Every year for the last 24 I’ve done some amount of climbing, and often with a curious mind towards how I might improve.

I mention this because I think it’s worth pointing out that (unless you’re at a world class level already) you don’t need to follow a strict training regime every day of every year to keep getting better, even into your 40s. And much like any other aspect of life, small improvements built on years of foundation can be quite rewarding.

The incredible Rose Weller sending iconic Nowra line, White Ladder (33). Image by Michael Blowers.