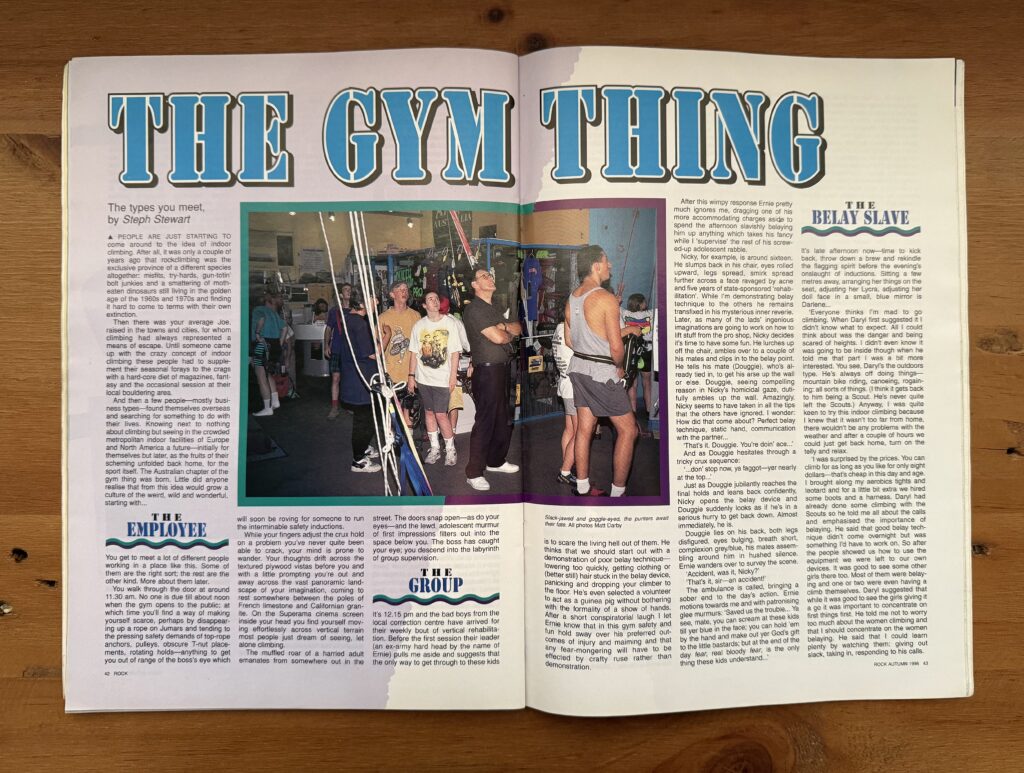

Climbing gyms are everywhere now — you can’t throw a chalk bag in a major city without hitting one. But rewind to 1996 and the whole idea still smelled a bit like a bad gimmick. Wasn’t climbing supposed to be about dirt, danger, and run-outs in the sun? Plastic holds and air-conditioning didn’t exactly scream adventure.

This article drops right into that moment — when indoor walls were just starting to creep across Australia, bewildering the old guard and hooking a whole new breed of climbers. It’s raw, it’s cheeky, and it’s a snapshot of the sport on the cusp of a cultural shake-up.

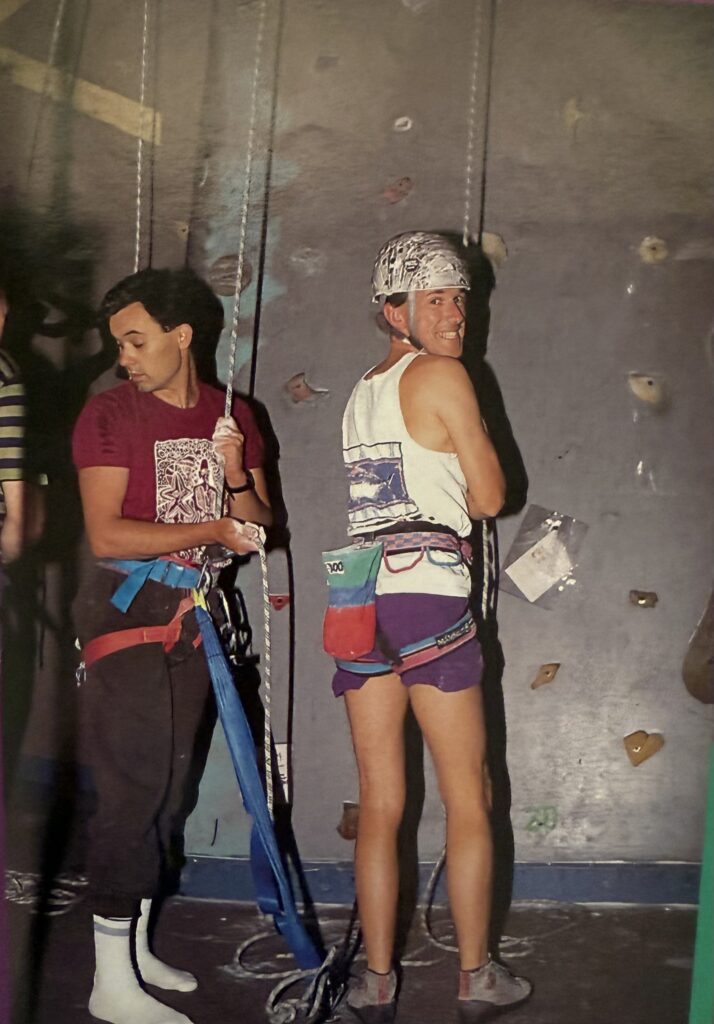

▲ PEOPLE ARE JUST STARTING TO come around to the idea of indoor climbing. After all, it was only a couple of years ago that rockclimbing was the exclusive province of a different species altogether: misfits, try-hards, gun-totin’ bolt junkies and a smattering of moth-eaten dinosaurs still living in the golden age of the 1960s and 1970s and finding hard to come to terms with their own extinction

Then there was your average Joe, raised in the towns and cities, for whom climbing had always represented a means of escape. Until someone came up with the crazy concept of indoor climbing these people had to supplement their seasonal forays to the crags with a hard-core diet of magazines, fantasy and the occasional session at their local bouldering area.

And then a few people—mostly business types—found themselves overseas and searching for something to do with their lives. Knowing next to nothing about climbing but seeing in the crowded metropolitan indoor facilities of Europe and North America a future—initially for themselves but later, as the fruits of their scheming unfolded back home, for the sport itself. The Australian chapter of the gym thing was born. Little did anyone realise that from this idea would grow a culture of the weird, wild and wonderful, starting with…

THE EMPLOYEE

You get to meet a lot of different people working in a place like this. Some of them are the right sort; the rest are the other kind. More about them later.

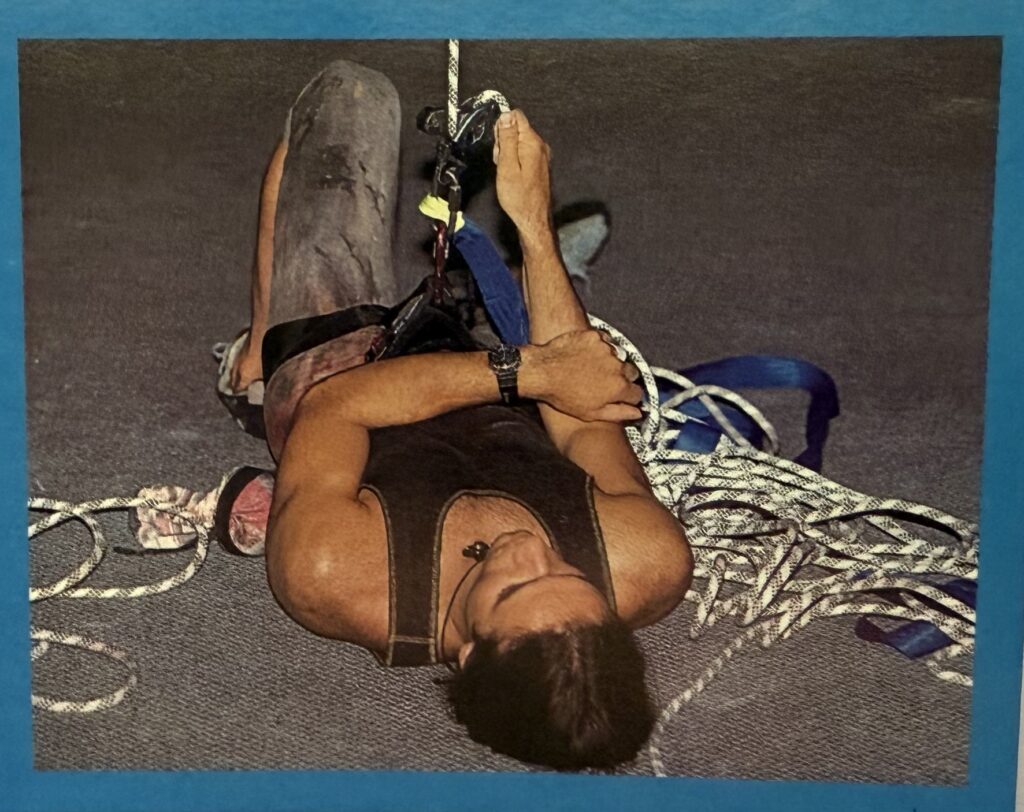

You walk through the door at around 11.30 am. No one is due till about noon when the gym opens to the public; at which time you’ll find a way of making yourself scarce, perhaps by disappearing up a rope on Jumars and tending to the pressing safety demands of top-rope anchors, pulleys, obscure T-nut placements, rotating holds—anything to get you out of range of the boss’s eye which will soon be roving for someone to run the interminable safety inductions.

While your fingers adjust the crux hold on a problem you’ve never quite been able to crack, your mind is prone to wander. Your thoughts drift across the textured plywood vistas before you and with a little prompting you’re out and away across the vast panoramic landscape of your imagination, coming to rest somewhere between the poles of French limestone and Californian granite. On the Superama cinema screen inside your head you find yourself moving effortlessly across vertical terrain most people just dream of seeing, let alone climbing.

The muffled roar of a harried adult emanates from somewhere out in the street. The doors snap open—as do your eyes—and the lewd, adolescent murmur of first impressions filters out into the space below you. The boss has caught your eye; you descend into the labyrinth of group supervision.

THE GROUP

It’s 12.15 pm and the bad boys from the local correction centre have arrived for their weekly bout of vertical rehabilitation. Before the first session their leader (an ex-army hard head by the name of Ernie) pulls me aside and suggests that the only way to get through to these kids is to scare the living hell out of them. He thinks that we should start out with a demonstration of poor belay technique—lowering too quickly, getting clothing or (better still) hair stuck in the belay device, panicking and dropping your climber to the floor. He’s even selected a volunteer to act as a guinea pig without bothering with the formality of a show of hands.

After a short conspiratorial laugh I let Ernie know that in this gym safety and fun hold sway over his preferred outcomes of injury and maiming and that any fear-mongering will have to be effected by crafty ruse rather than demonstration.

After this wimpy response Ernie pretty much ignores me, dragging one of his more accommodating charges aside to spend the afternoon slavishly belaying him up anything which takes his fancy while I ‘supervise’ the rest of his screwed-up adolescent rabble.

Nicky, for example, is around sixteen. He slumps back in his chair, eyes rolled upward, legs spread, smirk spread further across a face ravaged by acne and five years of state-sponsored ‘rehabilitation’. While I’m demonstrating belay technique to the others he remains transfixed in his mysterious inner reverie.

Later, as many of the lads’ ingenious imaginations are going to work on how to lift stuff from the pro shop, Nicky decides it’s time to have some fun. He lurches up off the chair, ambles over to a couple of his mates and clips in to the belay point. He tells his mate (Douggie), who’s already tied in, to get his arse up the wall or else. Douggie, seeing compelling reason in Nicky’s homicidal gaze, dutifully ambles up the wall. Amazingly, Nicky seems to have taken in all the tips that the others have ignored.

I wonder: How did that come about? Perfect belay technique, static hand, communication with the partner…

‘That’s it, Douggie. You’re doin’ ace…’

And as Douggie hesitates through a tricky crux sequence:

‘…don’ stop now, ya faggot—yer nearly at the top…’

Just as Douggie jubilantly reaches the final holds and leans back confidently, Nicky opens the belay device and Douggie suddenly looks as if he’s in a serious hurry to get back down. Almost immediately, he is.

Douggie lies on his back, both legs disfigured, eyes bulging, breath short, complexion grey/blue, his mates assembling around him in hushed silence. Ernie wanders over to survey the scene.

‘Accident, was it, Nicky?’

‘That’s it, sir—an accident!’

The ambulance is called, bringing a sober end to the day’s action. Ernie motions towards me and with patronising glee murmurs:

‘Saved us the trouble… Ya see, mate, you can scream at these kids till yer blue in the face; you can hold ‘em by the hand and make out yer God’s gift to the little bastards; but at the end of the day fear, real bloody fear, is the only thing these kids understand…’

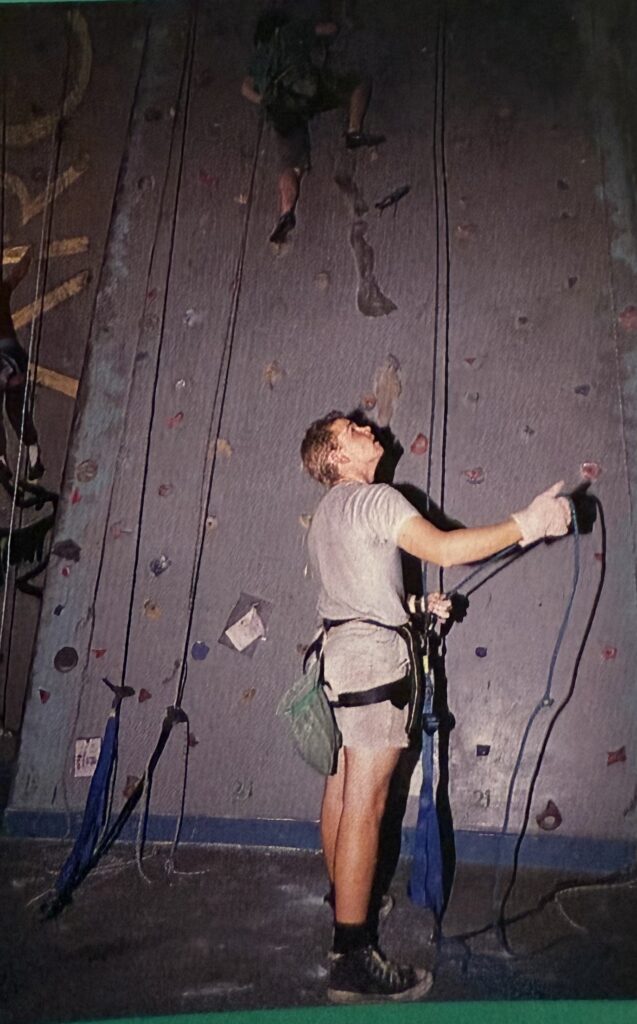

THE BELAY SLAVE

It’s late afternoon now—time to kick back, throw down a brew and rekindle the flagging spirit before the evening’s onslaught of inductions. Sitting a few metres away, arranging her things on the seat, adjusting her Lycra, adjusting her doll face in a small, blue mirror is Darlene…

‘Everyone thinks I’m mad to go climbing. When Daryl first suggested it I didn’t know what to expect. All I could think about was the danger and being scared of heights. I didn’t even know it was going to be inside though when he told me that part I was a bit more interested. You see, Daryl’s the outdoors

type. He’s always off doing things – mountain bike riding, canoeing, rogaining: all sorts of things. (I think it gets back to him being a Scout. He’s never quite left the Scouts.) Anyway, I was quite keen to try this indoor climbing because knew that it wasn’t too far from home, there wouldn’t be any problems with the

weather and after a couple of hours we could just get back home, turn on the telly and relax.

‘I was surprised by the prices. You can climb for as long as you like for only eight dollars-that’s cheap in this day and age. I brought along my aerobics tights and leotard and for a little bit extra we hired some boots and a harness. Daryl had already done some climbing with the Scouts so he told me all about the calls and emphasised the importance of belaying. He said that good belay technique didn’t come overnight but was something I’d have to work on. So after the people showed us how to use the equipment we were left to our own devices.

It was good to see some other girls there too. Most of them were belaying and one or two were even having a climb themselves. Daryl suggested that while it was good to see the girls giving it a go it was important to concentrate on first things first. He told me not to worry too much about the women climbing and that I should concentrate on the women belaying. He said that I could learn plenty by watching them: giving out slack, taking in, responding to his calls.

‘I picked up lots of good belay tips; things like being quiet, listening for your partner’s calls, lowering smoothly. Daryl said that I was already showing a lot of potential. My lowering in particular was very smooth for a beginner. Though I did come away from our first session with a sore neck Daryl was sure that this would become less of a problem over time, particularly if I practised some neck exercises he’d shown me. Daryl was only joking when he said ‘no pain, no gain’ but in a way he’s right. How can I expect to improve my belaying unless I’m prepared to work at it?

‘Since that first time, climbing at the gym has become a regular thing. Tuesdays and Sundays. My friends still think I’m crazy but I’ve never been scared to try something new and having Daryl teach me makes all the difference. He says that in a few months’ time we’ll look at me having a climb as well. While the thought is exciting, for the moment belaying provides more than enough challenges and its own special satisfactions. Daryl even thinks that it’s helped to improve his own climbing-knowing that he’s always safe and can trust me in the same way that I know I’ll always be able to trust him.’

THE DINOSAUR

Warming up at the base of the gym’s only hand-crack is one of the grand fathers of the sport. Threadbare, woollen shirt and trousers, heavily bearded, balding, thickening about the midriff and

conspicuously chalkless…’I can’t say I’m happy about these places. I’m only here to make my stand. To let people know that this isn’t ‘real’ climbing. It seems to me that these places are just another fad. Fibreglass walls, plastic holds, all these young people wearing Lycra…

‘It wasn’t so long ago that climbing was an experience. Hiking in with a loaded pack, setting up camp, finding water; getting yourself established in the bush before embarking on the climb itself. It was a real battle in those days. Just you, a few yards of hemp rope, some knotted slings and the hunger for adventure. That’s what it was all about. I can remember spending nights alone on small, vegetated ledges, hundreds of metres off the ground, without water and with only a few crumbs of food, no bivvy bag, shivering in subzero temperatures. No question of help or even of rescue. No, it was just you battling it out against the elements. And with a bit of guts and determination, obstacles were overcome rand routes were conquered. Today it’s all chalk and talk.

‘When I come to a place like this it saddens me to reflect on what’s become of climbing. A short drive, an entrance fee, a couple of minutes spent reviewing safety. In my day you weren’t allowed within a bull’s roar of a crag without a thorough grounding in safety and first aid procedure. And all these skimpy Lycra

outfits. How anyone’s supposed to concentrate with those kinds of distractions going on around them is beyond me. Army-surplus pants, a sturdy jumper, perhaps a skivvy if it’s cold. When things warm up you’ve always got shorts and a T-shirt. But here you have a place that’s coming apart at the moral seams all in the name of fashion. We’ve got to ask ourselves: what kind of example are we setting for the next generation? Anyway, I’d love to stay and talk but my partner’s getting a bit restless and we’ve only got a couple of hours.”

THE MUM

In the far corner a couple of kids are throwing themselves up one of the steeper walls and making a hell of a racket. Meanwhile a middle-aged woman sits bolt upright on an adjacent bank of seats, with a faraway look in her eyes…

‘This is the last place I wanted to bring them. You hear all those stories about kids falling off the cliffs ropes breaking, accidents, injuries: it’s more than any mother can bear. So you can understand that I only brought them down here as the last resort. The television has gone in for repairs, the youth club was closed by government cut-backs and it’s been too wet down in the park for the kids to play at anything except world championship mud wrestling (and you know how popular a sport that is among mothers

the world over). Anyway, one of the boys had seen some climbing on the telly (before it was broken), remembered the name of the place, phoned them and virtually had us booked in before I’d even had a chance to express my disapproval.

‘At first I wasn’t going to have a bar of it but after two solid weeks of nagging I caved in and told Edward he could go; he’s always been a responsible boy and I knew that I could rely on him to look after himself. Within minutes of my decision he and his brother Daniel were at me again, this time to let Daniel go along as well. They told me that you needed two people-one to hold the rope, the other to climb. They said it

I was for safety. Those boys, they know me too well. I told them I’d have to think about it and talk things over with their father. They said he’d already agreed. With the pressure mounting | succumbed and told them they could go, I’d even give them the money as long as they were careful. I took Edward aside and let him know that I was holding him personally responsible for his brother’s welfare. He told me that would cost an extra fiver-perhaps he’s become a touch too sensible lately.

‘I consoled myself with the fact that at least the boys’d be out of my hair and off the streets. It was then they came back to me with the king-hit. Not only was I going to have to worry myself sick about them; I was actually going to be there. Apparently some insurance thing meant that the kids had to have a guardian present. Roger was flat out at work and so it was left up to me. I’d given my word. There was no turning back. ‘So here I am, gripping the plastic bench seat with both buttocks and both hands, my knuckles whitening under the pressure, staring fixedly out of the one window in the place. I can’t see the boys; I don’t want to see them. But I can’t block out the sound-the shrill, adolescent screams shifting between panic and exhilaration. They made me sign some- thing; the ink is a blur! I close my eyes,

clamp them shut, take some long, deep breaths and visualise the dirty washing. My kingdom for a basket of dirty washing…

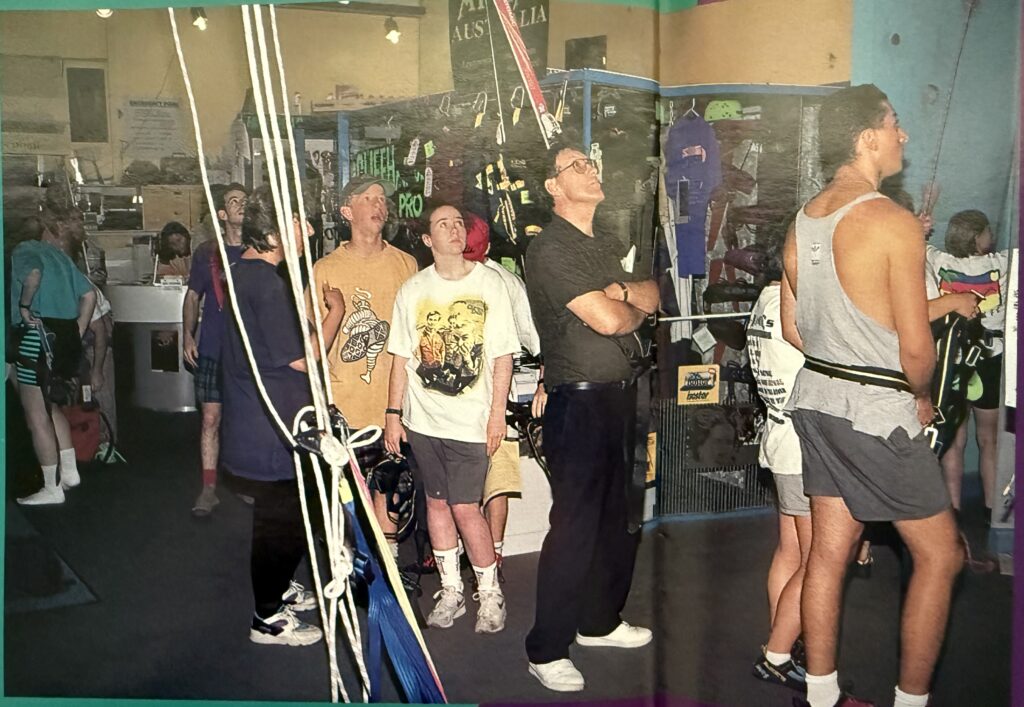

THE ROUTE SETTERS

At an ungodly hour every Monday morning we route setters congregate in the bowels of this crazy establishment for our weekly rituals. Coloured plastic holds strewn across the carpet, Jumars, krabs,

étriers and a vast, plywood canvas laid out before us. We mill around, anticipating the creation of our latest masterpieces. Talk, talk! You haven’t heard this much talk since days gone by, huddled together in someone else’s lounge room reliving former glories or, failing that, inventing them.

Hands in pockets, the latest ‘goss’- who’s done what to whom, and why. A long, hard look at the vacant walls and the vacant faces of the others trying to Snap themselves out of a post-sleep stupor, or in some cases a post-birth stupor. You slip into your harness and wait for the arrival of the ‘expert’ route setter the management has hired; then she walks through the door. You’ve seen her somewhere before. You can’t quite make out where and you’re not even sure that you want to. With a shake of the hand and a tousle of the hair she makes her acquaintance with the regulars. Her weird drawl sounds like something from the west coast of the USA with the occasional lapse back into the local tongue for effect.

A consummate professional, it doesn’t take long before she’s dragged the focus away from herself and on to the task at hand. Apparently we’re about to get some hot tips on how to set real routes. Do this! Do that! Don’t be tempted to try anything along these lines and whenever you can, avoid doing the opposite! Get the idea? I guess this is the management’s concept of training. Not that anyone’s taking anything in.

Hell, no! Subconsciously we’ve all created our own little edifices, our egos balanced precariously on top of them while others simultaneously excavate the foundations in an attempt to bring the whole, brittle thing tumbling down. She’d have more luck trying to change the weather. Within moments we’re halfway up the walls-hungry for the next classic having dutifully forgotten everything she’s told us.

Hours later and you describe your handiwork:

‘Oh it’s a latter-day classic, mate. Committing traverse into hard laybacking up a steep arete; rock left on to the headwall; mantel into a sequential crux and stick three successive dynos for the tick. They’re not going to want to pull this one down in a hurry, fellas. The grade? How can you give a route like that a

grade? What did they give a Da Vinci… a B+? But don’t take my word for it, get on the thing. It’s National Trust material, National bloody Trust…’ But ten minutes later the critics say:

‘Sorry, Simey, it’s still reachy…’

‘Stick with the off-widths…’

‘That’s the work of a seriously diseased imagination…

‘It’s a sensation, mate-until you leave the ground.’

‘I’ve climbed better routes on a felled tree!’

So that’s a taste of the gym thing. Bull and wank cosmically leavened by the occasional worthwhile route. Too much heaving skin, too many aspirations. Numbers, bumblies, numbered bumblies fattening the till, greying your hair, wrinkling your face, turning you off and turning you on. It’s not quite Arapiles but then Arapiles isn’t 15 minutes away…

About the Author: (1996) Steph Stewart is a climber who has spent five years studying film, drama, literature and outdoors education at Melbourne University. He is partly responsible for the construction of both a well-frequented inner-Melbourne bouldering wall and the Cliffhanger Climbing Gym. He has climbed extensively in Australia as well as in the USA and Thailand.

More Articles: