On the loose

First Published in Rock Magazine Jul-Dec 1993

Written by Simon Mentz

This article was originally published in Rock Magazine in 1993. The information, route descriptions, and access details reflect the conditions and ethics of that time. Climbing areas and their access arrangements may have changed significantly since then. Please consult up-to-date local sources, land managers, or climbing access organisations before visiting any of the locations mentioned.

Ewbank, HB…and terror on a new Blue Mountains mega-route; Simon Mentz is still babbling

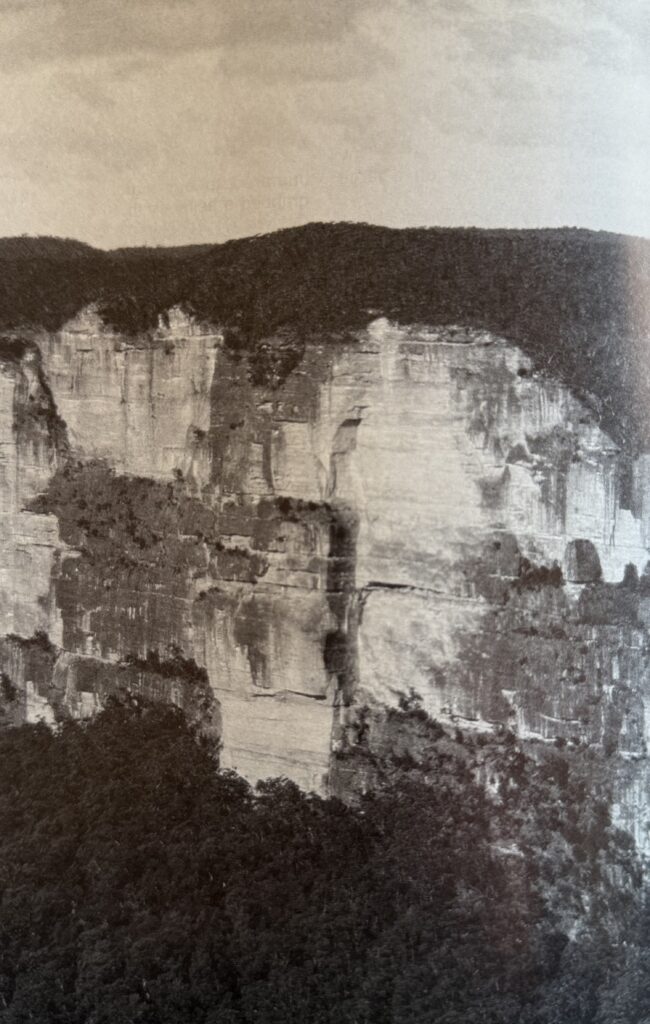

WOW! THAT MUST BE IT, H. What a line!’ ‘Mmmm, Ewbank wasn’t exaggerating when he said it blanked out near the top.’ ‘Yeah, I thought he said the corner ended 40 feet from the top. That’s at least 40 metres.’ ‘Check out how much it overhangs up there.’ ‘Looks like your lead on that one, HB. Congratulations.’

We were standing at Evans Look-out in the Blue Mountains, which overlooks the magnificent Grose valley. Being a popular look-out, the line we were eyeing was no great secret. Any climber who stood there would undoubtedly be drawn to the 180 metre corner across the valley.

In 1968, Australian climbing legend John Ewbank had marked it down on his hit-list as a potential new mega-route. A preoccupation with putting up horrendous routes on Dog Face and then a premature departure from the climbing scene into the music industry meant that he never managed its ascent.

However, 25 years later the line remained unclimbed. Big lines were out of fashion. Except for a few die-hards, the majority of rockaholics were now bolting short and uninspiring ‘sport’ routes. Adventure was out and lots of bolts and big numbers were in.

An invitation to speak at Escalade ’93, a desire to get back into climbing and the discovery that ‘the big corner visible from Evans’ was still unclimbed, prompted Ewbank into action. A meeting with Malcolm Matheson (also known as HB or even just H) and a shared interest in ‘adventure climbing’ resulted in an agreement to meet a few weeks later to bag some big lines.

I tagged along at HB’s request. Whatever might eventuate, I brightly figured that climbing with these characters would have to beat a week of dogging my way up obscure gully routes at Mt Arapiles.

Most experienced climbers are well aware of John Ewbank’s contribution to Australian climbing in the early 1960s. For those who aren’t familiar with the vast number of classic climbs he established throughout the Blue Mountains and elsewhere, rest assured that at least you have used the Australian grading system which was his creation.

Ewbank’s whole approach to climbing was probably ten years ahead of his time. Climbing in the 1960s was something you did every second weekend if you were keen. His dedication would have been more suited to the full-time approach taken by the ‘New Wave’ of the late 1970s. One of his lesser known and certainly least desired achievements was to be probably the first Australian climber to wreck his elbows from overtraining—the result of 1000 chin-ups a day in sets but with no rest days in between.

After meeting up with ‘Mr Ewbank’ in the Blueys we soon learnt all about the ‘Big Corner’. The following day HB and I drove out to Evans to have a look. Unfortunately, Ewbank was feeling ill and we weren’t able to make a start. Instead the two of us headed for Dog Face.

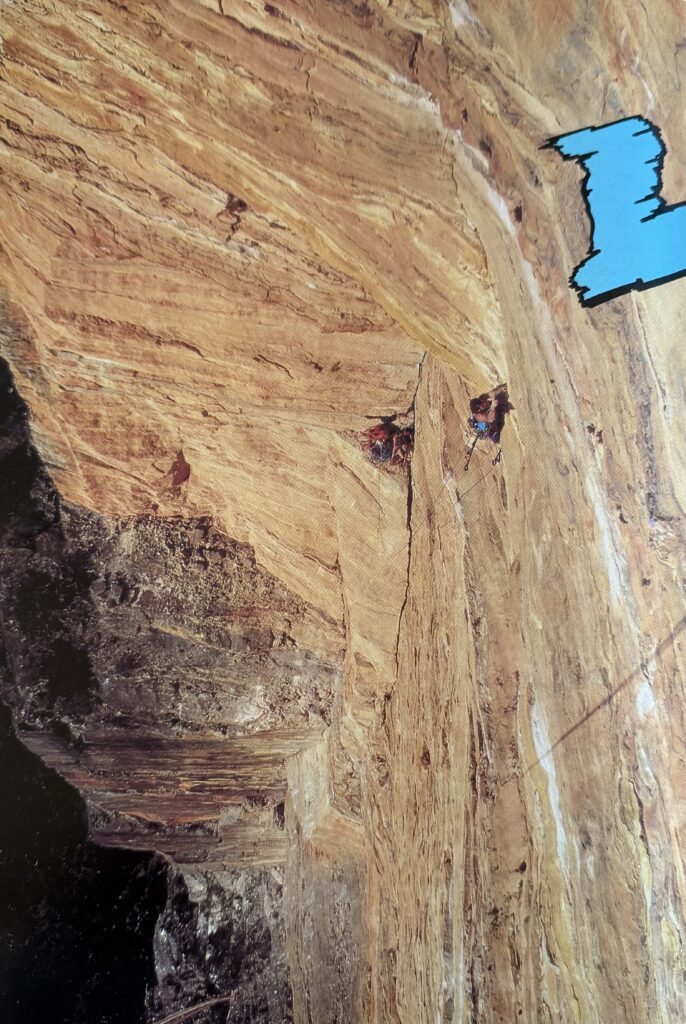

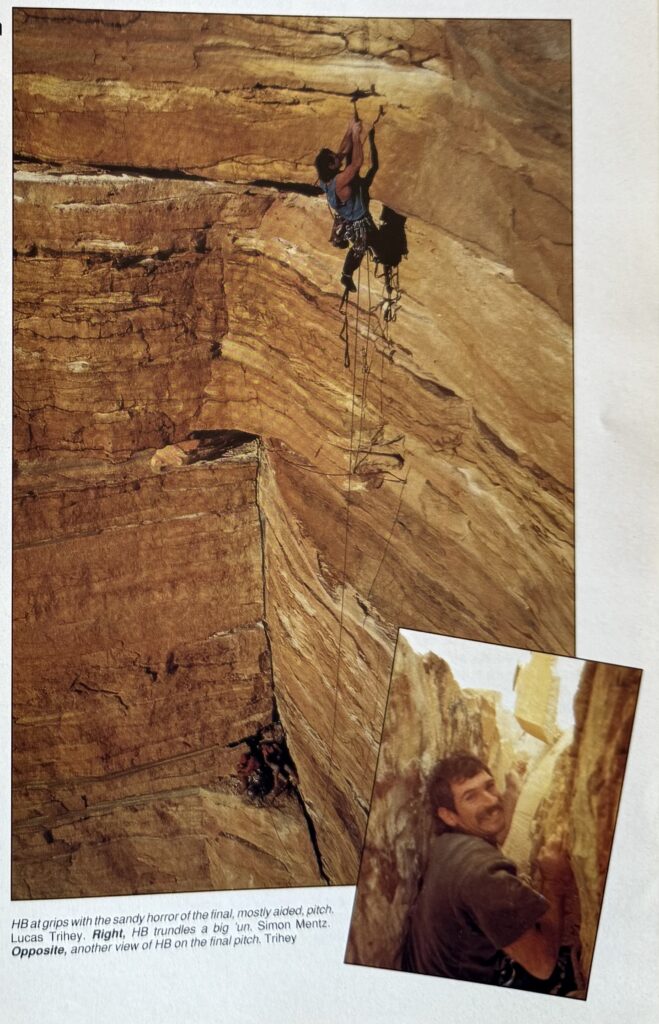

Left: HB at grips with sandy horror of the final, mostly aided, pitch. Lucas Trihey. Right: HB trundles a big ‘un. Simon Mentz Opposite: another view of HB on the final pitch. Lucas Trihey.

On Ewbank’s recommendation we thought we’d try freeing Giant, an old aid-route of his. The first pitch was solid climbing on not so solid rock and it took HB a little while to adapt to the sandy nonsense. After a shaky start he soon got into the swing of things, but we ran out of daylight by the time I had finished leading the second pitch. We came back later and topped out with the route free at grade 24.

It had been a great climb but our attempt on the big corner was to be a venture into the unknown. Despite our suggestions that we rap the route first and maybe place a few bolts for a free climbing attempt, Ewbank was adamant that he wanted to deal with the problems as they arose. Regardless of whether the route was free climbed or aided, the adventure lay in climbing the corner from the ground up.

On the morning of our first attempt we wasted some hours bashing round aimlessly trying to find our proposed rap route. Three ropes connecting various ledges took us to the bottom of the cliff. We eventually got started on the climb.

Ewbank tied a chalk-bag round his waist for the first time ever, lit a fag, then began leading the first pitch. Despite the deluge of sand and rock that rained down on our helmeted heads, Ewbank reached the belay and told us it was a ‘nice little pitch’!

HB led the next pitch which ended with a lovely, sandy ramble to a long, convenient terrace from which our abseil ropes were accessible.

The third pitch was a sky-rocketing corner. It looked impressive and even solid. It was my turn to lead so I launched on up, glad to be getting the best-looking pitch so far. The pitch was a combination of sustained bridging, jamming and laybacking, but the rock was a far cry from my beloved Mt Arapiles.

At one point a sizeable loose block sat precariously on a small ledge. While I felt nervous bridging delicately round it, Ewbank probably felt twice as nervous watching me. He was directly in the firing-line. Fortunately, I reached the belay without incident, but due to oncoming darkness the others didn’t have time to follow. I rapped off leaving the rope set up as a big top-rope and we got ready to Jumar out.

Jumaring is never much fun at the best of times, but being 23 years since he last clipped into a pair, Ewbank managed to stuff up his sling lengths and turned 130 metres of Jumaring into something that must have felt like 1300 metres. At the top his elbows were trashed and he felt frustrated. HB and I were also depressed. Three pitches in one day was pretty slow progress and we still had all the hard climbing to come. We headed out to Katoomba for a big feed.

On the following day there was rain, which gave Ewbank a chance to rest his elbows. The next day still looked doubtful, but we decided to go for it.

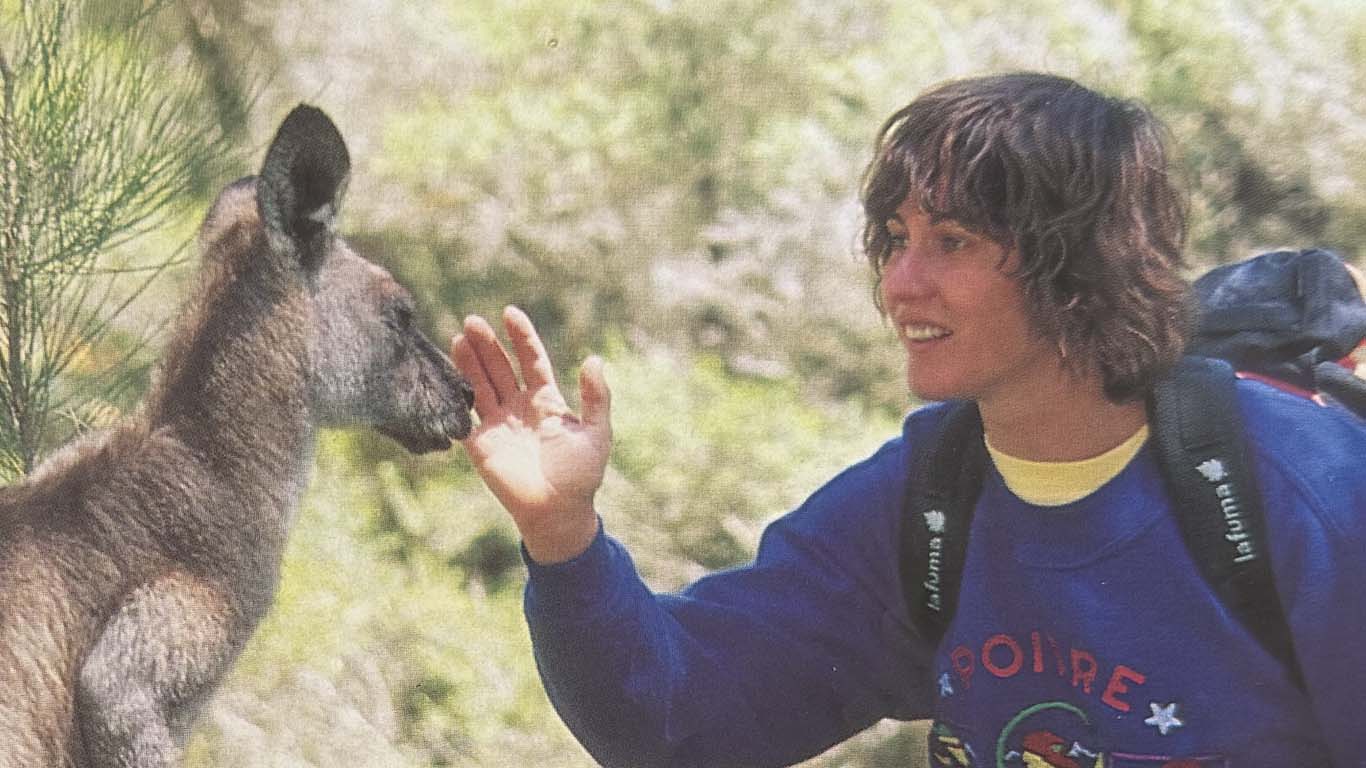

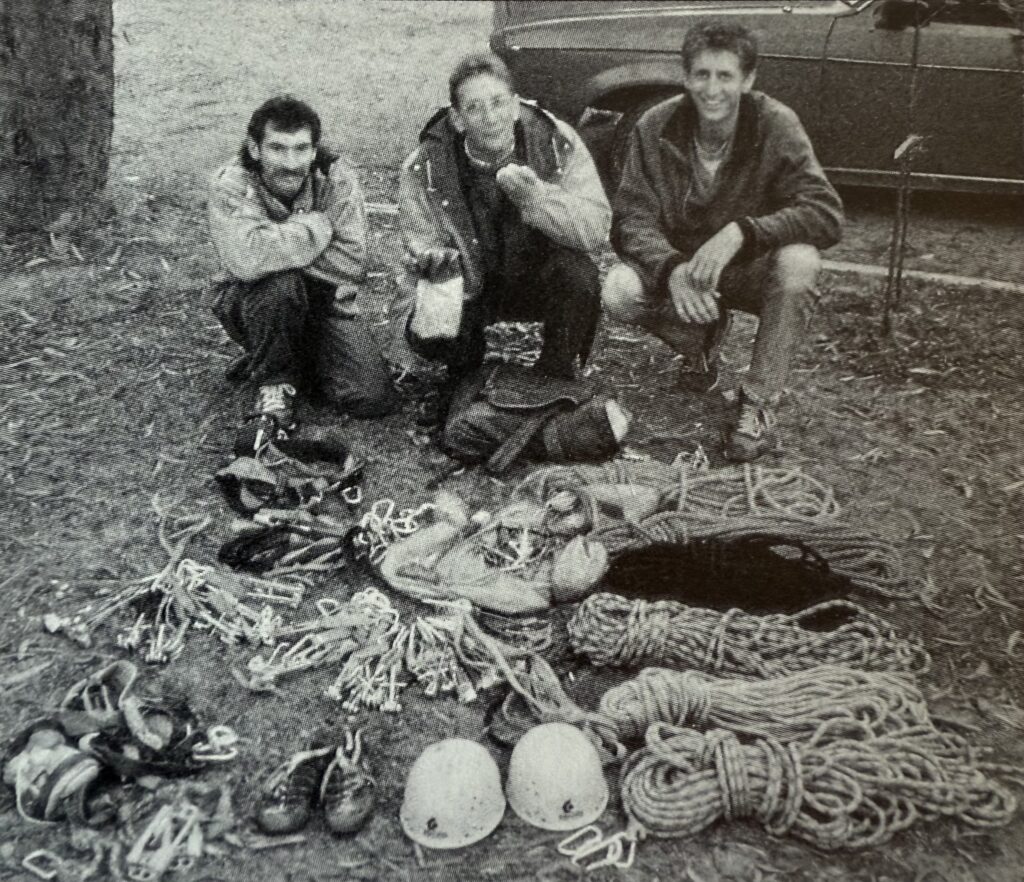

HB (left), Ewbank (getting his first whiff of chalk), and our hero Mentz, with the physical wherewithal for their adventure. Lucas Trihey.

Back down the abseil ropes, then HB and I climbed back to my high point. From there HB led through, up a short but steep and loose crack. The crack was filled with detached blocks that were dubiously wedged in. When jamming the crack the blocks sometimes shifted and you would partially slide back. At one point, HB tried to move out of the disconcerting crack by reaching for a large hold, but the whole thing ripped off the rock-face and plummeted past me. It caused HB to barn-door right away from the cliff but he managed to muscle back into the crack before peeling off.

After that little drama HB traversed delicately on to slightly easier ground and then moved up to belay on a large, ominous block.

The lack of any adequate natural protection meant that HB had to start drilling a bolt belay. Meanwhile I started belaying Ewbank up the corner. Surprisingly, HB finished hand-drilling a double-bolt belay by the time Ewbank had arrived at my ledge. This wasn’t because Ewbank was slow, but rather because the rock was so soft that it took HB only 20 minutes to place both three-and-a-half inch bolts!

After following HB’s short pitch, we sat reunited on the ominous block. The rock was certainly far worse than we had ever imagined and glancing up it didn’t look any better. It wasn’t surprising that the climb had never been done. I was really freaked out. Ewbank, however, was loving it and was very happy to be doing the line at long last. Even HB seemed to be enjoying the whole crazy venture.

Somehow I got the next lead. Against my better judgement I started up another long and spectacular corner. This time the climbing was quite easy, but the rock was doing the impossible and deteriorating even further. After ten metres I moaned about my situation to the others. After 20 metres height I was weeping.

Ewbank yelled up encouragement but I began to think that he and HB were both crazy. I wanted out, but there were no good runners to lower off. I brushed my hand against the wall. Great hunks of flaky, sandy shit fell off. I looked up. I figured it might get better and made another move.

There are lines and there are lines…’ The Big Loose Corner.

During my lead, HB and Ewbank amused themselves on the ledge below. In between dodging the debris I sent down, HB gave himself the task of levelling out their small ledge. While trundling off hundreds of kilos of loose rock and shale, he managed at one point accidentally to shift the whole block on which they sat. If the multi-tonne block had fallen away they would have both been dangling off their belay!

After 40 minutes of very slow climbing I reached the belay, a sloping shale ledge. It was obvious that we weren’t going to finish the climb that night. I brought HB up and he quickly drilled another double-bolt belay from which we rapped back down.

Each night we headed out to enjoy the comforts of eating and sleeping in civilization but this had its drawbacks. The mind-set adopted during the day to deal with the fear suddenly wasn’t needed. However, sitting in Tom’s Eats and recalling the horror would have my stomach churning. The thought of leaving this comfort and having to go through it all again the next day made for a very restless night’s sleep.

The following day dawned bright and beautiful. Too nice a day to die, I reflected as I checked and rechecked the rope, the anchors, my harness, my screw-gate and anything else that was essential to my well-being.

After rapping back down, HB and Jumared to our high point. Ewbank grabbed a belay so that he could follow the pitch I had led the previous day. Afterwards he congratulated me on having one of the loosest pitches in the Blue Mountains to my credit. That meant a lot to me coming from someone with plenty of experience in such matters!

Ewbank demonstrated his ability on loose rock by his efficient lead of the next pitch. A short traverse, on rock so manky that it was green, led to a corner crack. The final few metres widened to the point where Ewbank had pushed the number four Camalot as far as it could go and then ran it out to the ledge, bridging off some pretty doubtful stuff. It would have been a trying lead and showed that Ewbank hadn’t lost his touch.

All that separated us from the top now was the big last pitch. It was HB’s lead and Ewbank and I knew that there was no one better for it. But even with the ‘H factor’, this was going to be a time-consuming lead and so Ewbank and I made ourselves comfortable by redecorating the ledge and trundling off some blocks.

HB led off, free-climbing the corner before it blanked out. He then traversed to the right and up into steeper country. The rock was still incredibly soft and HB switched to aid-bolting, hooking, pegging, placing the odd Friend, or whatever else made upward progress.

Ewbank and I had it easy. Our ledge was soon out of the line of rockfall so we basked in the sun, chatted, told jokes, sang and every now and then payed out another metre of rope.

A little later we looked up and saw a rope lower over the edge. Lucas Trihey and camera soon followed. Lucas had been aware of our progress and figured that the last pitch might be quite photogenic. He was in an outrageous position and watching him casually twirl round more than 150 metres above the deck compelled Ewbank to call out more than once, ‘Be careful, Luke’.

Meanwhile HB’s progress was momentarily halted when he took a five metre fall. Unfazed, he quickly regained his high point and moved on past. Due to the limited number of bolts, HB came up with a revolutionary new bolting technique.

While we were already using carrot bolts, where you have to place your own hangers (an idea that most visiting overseas climbers find bizarre), HB took this one step further and removed the bolt! He was basically employing the same technique as hooking off drilled holes, but this allowed better security due to the softness of the rock. Every now and then HB would leave a bolt, as secure as possible, as a runner.

Towards the end of the day we began to fear that the rope might not reach the top. The thought of a hanging belay on poor, soft rock on an overhanging wall seemed an unjustifiable risk. As Lucas Jumared out, HB called for him to leave a fixed rope near the cliff edge in case we didn’t make it.

With about ten metres to go, the sun set and HB pulled out the head-torch. For the next hour and a half all we could see was a little bobbing light and hear the thwack, thwack, thwack of his hammer. We knew he was close to the elusive top when he asked for all the, precious little, rope that was left.

A yell echoed in the darkness. Communication was difficult, but we figured he had pulled over the top okay. As we learnt later, HB had quite an exciting exit. From his last bolt he had made three consecutive hook moves. Rope drag was horrendous, so after pulling up all the available slack he stepped out of his etriers and tried to mantle on the shale ledge. Just as he was precariously rocking over, the rope pulled tight, threatening to drag him off. Knowing Lucas’s rope was off to the side, he snatched for it and flopped like a beached whale on to the ledge.

Being a shale ledge, a decent bolt belay just wasn’t possible and despite the three bolts HB placed, it still had to be backed up by the fixed rope.

It took quite a while before Ewbank and I eventually reached the ‘summit’; the Jumaring was quite an epic. We had to hand it to HB, it had been a real ‘Warren Harding’ effort on a pitch that did little to encourage you.

The Big Loose Corner, as we decided to call it, certainly hadn’t been the classic we might have imagined, but the three days spent on it were summed up by Ewbank when he said: ’Doing this climb with you guys means more to me than doing 50 sport routes.”

Looking back on it, I think both HB and I would agree.

UPDATE: In August 2025, the entire pillar of Carne wall collapsed due to a landslide.

The climb mentioned in this story was called The Big Loose Corner (21 M5) 220m (8 pitches), first ascent by John Ewbank, Malcolm Matherson & Simon Mentz, completed over 3 days. There was no logged second ascent.

Another historical piece that may interest you: Fear and Loathing – The Sea Cliffs of Sydney