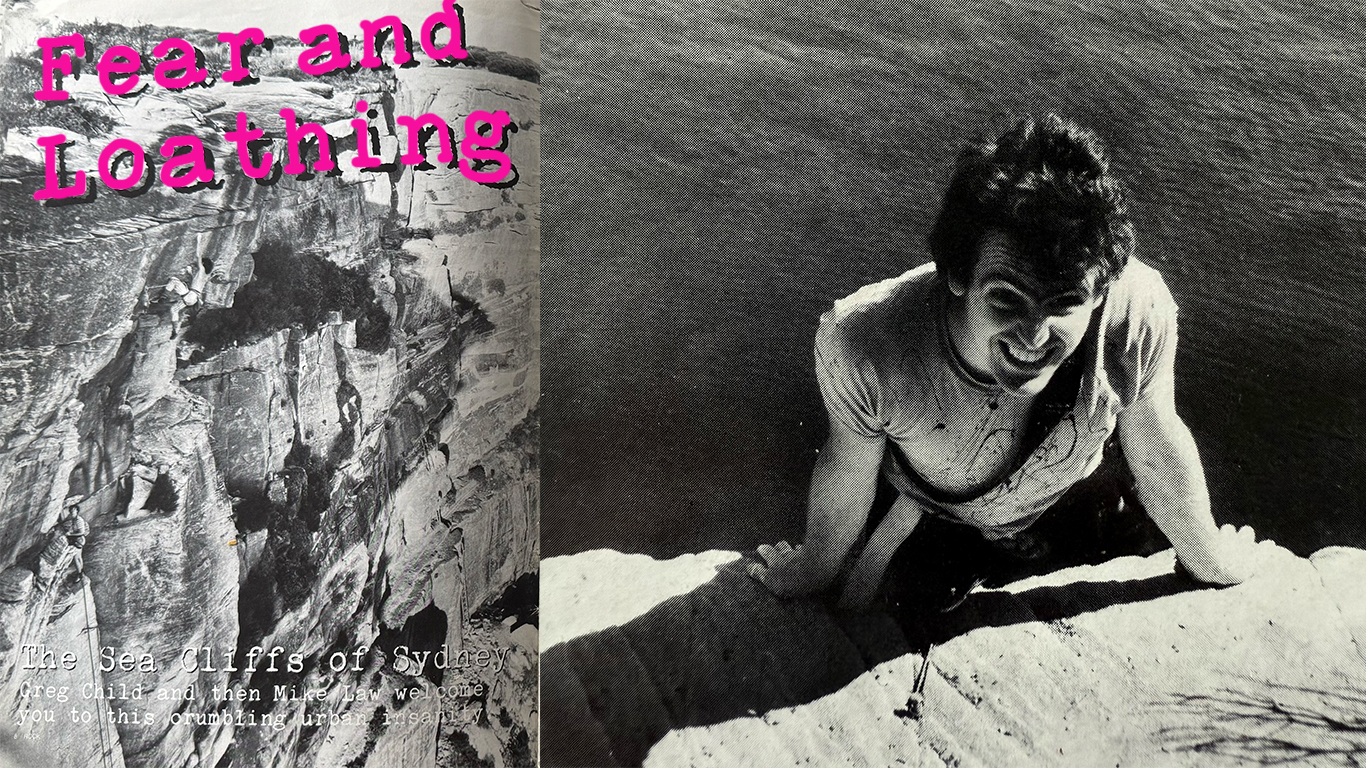

Fear and Loathing - The Sea Cliffs of Sydney

First Published in Rock Magazine 1983

Greg Child and Mike Law welcome you to this crumbling urban insanity.

This article was originally published in Rock Magazine in 1983. The information, route descriptions, and access details reflect the conditions and ethics of that time. Climbing areas and their access arrangements may have changed significantly since then. Please consult up-to-date local sources, land managers, or climbing access organisations before visiting any of the locations mentioned.

A grim, glorious plunge into the sandstone psyche of urban climbing—where the rules are loose, the bolts are rusty, and the ethics are optional.

Out here on the perimeter we have no ethics. It’s such a dog eat dog world we can’t afford the luxury. This peak hour traffic could swallow us up forever and no one would ever know, I think to myself as Claw whips the Ducati 500 between lanes of fuming cars. I see on my left a row of side mirrors each with images of two fools on a motor bike, and wonder if the next one I see will be the last. Like parting snapshots I close my eyes and the idea goes away.

When I reopen them I notice the ocean and realize that we are but 100 metres away from The Gap. Smelling smoke I look down to see a couple of sparks and some black acrid fumes rising from the vicinity of the engine. I nervously tap Claw on the shoulder and point to the problem. He kills the motor and as we coast the last few metres reaches down with one hand and pulls the battery out of its casing. Claw retrieves it, explaining that the bike has seen better days.

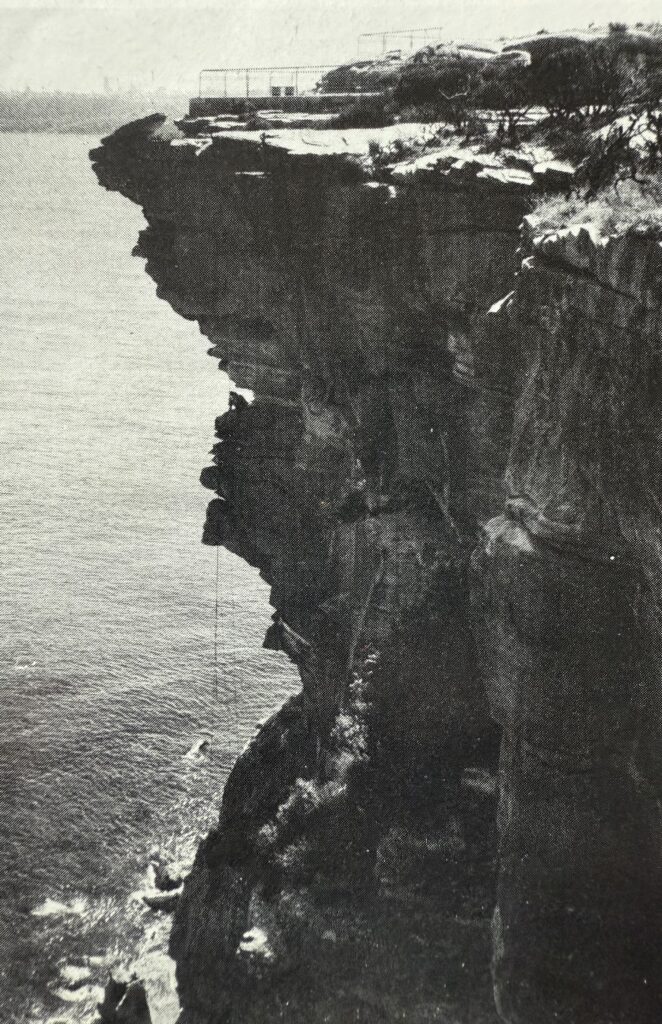

Standing at the bottom of The Gap is like standing inside a big amphitheatre that leans over at you. The angle is ridiculously steep. Its floor is a sprawling wave platform dotted with pools and denizens of the not-so-deep.

The Gap was once a household word, well known for its headline suicides. Alarmed police have ordered climbers off the cliffs, screaming orders through megaphones, perhaps presuming they were averting a suicide of elaborate, roped proportions. Can’t you just see the headlines in the Sunday Mirror: ‘Police avert multiple suicides by Sydney bondage cultists?’ But no, it never happened. In fact the place lost its charm as a launching pad. The encroachment of climbers may or may not be to blame for that.

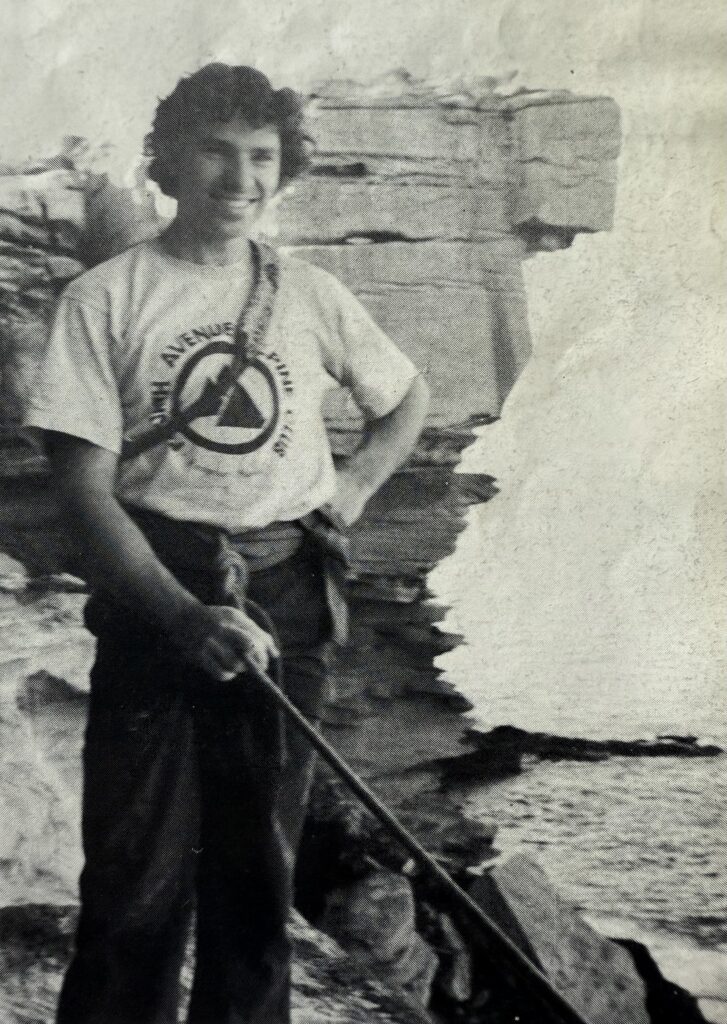

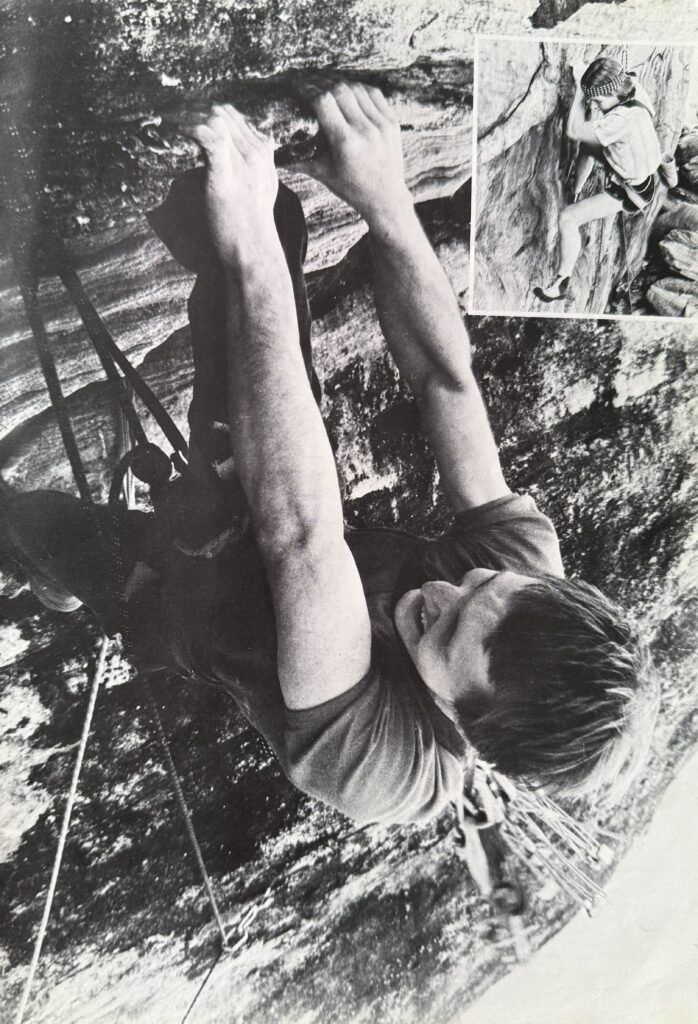

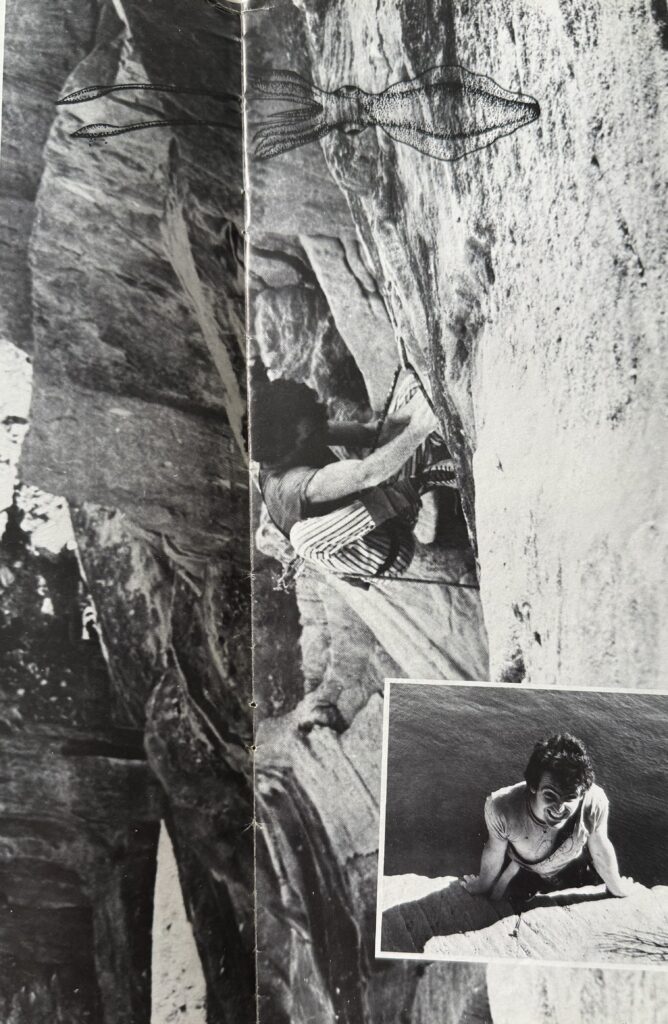

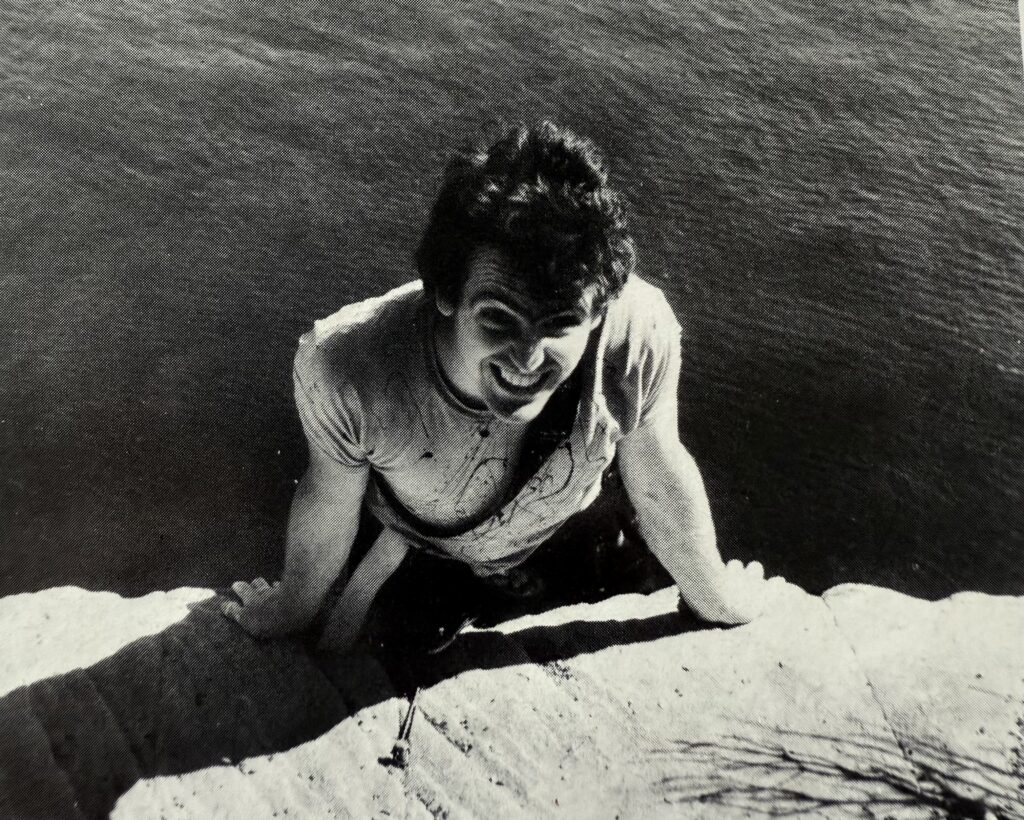

Left: Greg Child, Right: Giles Bradbury on Wrinkle City (20), and inset, Warwick Baid at grips with Surrogate Sickle (21). Glenn Robbins

Waves are rolling in towards The Big Dipper (24), breaking level with the roof, putting it out of the question. This is one of the best routes on the cliff, on the far right hand end. The approach involves running across a barnacle platform, between waves, and jamming up a short corner to a stance, where the belayer inevitably gets swamped. The climb swings through a large ceiling to a disturbingly thin face above, finally exiting to a mantel on broken glass and pre-war barbed wire. Belay on a crumbling gun emplacement.

To the left is Cruise or Bruise (21), drier and more straightforward, a slanting corner on decent rock. And to the left again is our objective for the day, which we’ve flailed on before. Not so much a line but more a series of features connected by cruxes.

Claw repeats the first pitch, a thin face protected by bolts leading to an undercling round a crumbly, phallic flake, to a belay stance. The next pitch follows a ramp to our previous high point, a bolt beneath a one metre roof. After a few tries I find a way through the roof and enter a series of grooves. A wind whips up and my shirt tail begins to flap in the breeze. The angle is absurd and quite terrifying but big buckets seem to appear with relieving regularity, till a hand-crack arrives at the top, with its freshly smashed beer bottle and empty chip bag impaled on a strand of barbed wire, blowing in the wind like a wind-sock.

Peak hour traffic now and we weave across downtown Sydney. I keep an eye out for smoke but the battery behaves itself. At a red light Claw flips his vizor up and turns round.

‘I know what we should call that route’, he says.

‘What?’

‘Snivelling Grooves.“

‘Right, Snivelling Grooves, a triumph of the will.’

Before we proceed any further I think it is both timely and opportune to include a word on ethics. Well, there are none really. They are only a hindrance to this sort of climbing. And anyway, if no one can see you what difference does it make, especially since no one is likely to ever repeat the routes? They might fall into the sea next week or decay into totally unrecognizable shapes next year. Sea cliffing is a sub-sport of climbing, a world apart and a law unto itself.

Basically a line here, unless a crack or other such fissure in the earth’s crust, is a series of holds that adhere to the wall long enough to enable someone to get to the top. Since the holds are not guaranteed to be around very long, neither is the protection, which brings us to the sole rule of the sea cliffs. Don’t fall. Which returns us to protection-bolts. The only thing that seems to go in sometimes is a bolt. The harder the climb the bigger the dose.

Of course prior inspection goes without saying. Old buses and winos have to be removed from rappel, and nasty cruxes can be tamed in this fashion. Railway spikes work well in horizontal breaks and nuts are occasionally useful. Nevertheless the nature of the climbing remains poorly protected and insecure. Perhaps in this aspect we see its greatest attraction. The adrenalin fix.

Running on empty in my battered EH Holden, we were headed towards Bondi for an exploratory visit to investigate a rumour about a fabled red wall beneath a golf course, The conversation had shifted from the usual character assassinations to a bad mouthing of the sea cliffs in general. So what was it that made us return time and time again, like lemmings? Was it a search for the wilderness experience? I think not. I think it was the antithesis thereof, but it runs deeper still.

We were entering a phase in our lives that was more than merely satisfying the elusive egoism and excitement found on most climbs. We were unwittingly becoming involved in a social statement that reached beyond the bounds of climbing itself. We were foresaking week-ends in the Blue Mountains for the short drive to the sea cliffs. We were relinquishing the security of good rock for bad rock. We were giving up the peace and quiet of the mountains and replacing it with the clamour of the city. We were… what were we doing? What evil and retrograde spiral were we embarking on? Was it madness? Was it some form of self-inflicted penance we felt we must pay? Was this the de-evolution of climbing?

Perhaps, but I sensed more. I began to draw a correlation between the crumbling edifice of society and our preposterous goings on upon these cliffs in which I could see our climbs as artistic statements and messages. But our methods were deliberately irrational and we had negated the laws of beauty and organization that are held to be the ethics and basis of climbing. Were we then the unwitting dada-ists of climbing, the first wave of the new wave?

As I parked the car I felt that I half understood what it was that we were doing. The medium and method had begun to clarify, but the message remained hazy, I looked across the golf course, toward the tall chimney of the treatment works and out to the cloudy ocean, trying to put it all together in my mind. Then, as if he knew what I was thinking, Claw turned to me and said: ‘You could say that the development of the sea cliffs represents a commitment to city life footholds that smeared into oblivion, that is as strange and perverse as it is inexplicable.’

So that was it – to simultaneously embrace the city and condemn it for what we know it to be. To accept the filth, the noise and neurosis, the crowded crime-ridden aberrations of city life, because we are a part of it just as it is a part of us; and then turn it about on itself to create a damning and cynical jibe at this ugly urban existence. What better expression of this, to us as climbers, than to climb on the rubbish surrounding the city?

We headed across the golf course, dodging white streaks that were golf balls when they stood still, and came to the edge of a steep red wall that dropped away to a broad wave platform. This was it. To one side was a remarkable sight; the Black Filth Couloir, as it came to be known, was a gully composed of trash, concrete, old cars and such stuff, piled so high as to form a breach in the cliffs.

Glissading down we came across a fossilized car, rusted fast to the rocks,a barely recognizable blob of steel and oxides. Perfect. This is what the whole city will look like in 1,000 years. And then the wall- a brilliant sun-burst of rock, overhanging continuously, flakes worming their way through tiers of bulges. Claw was running about the base screaming ‘fabulous, fabulous’.

To its left was yet another gargantuan piece of architecture. A rotten wall, pock-marked with honeycombed faces and tottering roofs, resembling an ancient block of flats with the front blasted off. Mal pointed to it and howled his derisive howl. ‘That’s no cliff Mal’, I said, ‘that’s an anti-cliff.” A golf ball arced overhead, bounced once on the platform, then splashed into the drink.

The ensuing siege of the Red Wall was a long and sordid saga that did much to further twist the author’s mind and ethics. Some dozen or more bolts, a railway spike and countless attempts by every man and his dog finally saw Claw fall up the route one calm day in July of 1980. Recollections are scant, but I recall laybacking peeling flakes, footholds that smeared into oblivion, in the manner that one stamps out a cigarette butt, with a delicate twist of the toe, and bolts drilled into mud. History knows the route as Grand Mal (24). Great art, someone once said, should always be disturbing.

North Head, the northern extremity of sea cliffing to date, is an equally strange and surreal place. The fisherman’s descent, via a network of chains and ladders, is a horror in itself, and the graveyard of smashed and tortured cars at the base is a memorial to vandalism. The routes themselves are a never-ending wonder of bizarrette.

Albatrocity (19) takes a system of corners and aretes bisected by a 100 metre ledge sporting a bunker at one end and an old elevator shaft at the other. Scrabble (15-19) begins at a variant fisherman’s descent, the first pitch of which is a ricketty 12 metre ladder. The second pitch fell on to the ladder, removing several rungs. Therefore the first pitch is now regarded as the crux. Drop Bears (19), is reportedly scary, with the only protection piece being the aid point.

The well-known North Head Bolt Route is a trip in its own right and is probably the most frequently ascended sea cliff route to date. Internationally famous climbers have been tricked into doing this one. A mystery surrounds the first ascent of The Bolt Route. The inimitable Claw, at the time a mere schoolboy, attempted it in the dark ages, prepared for a long lieback to glory through the spectacular arching corner. Instead he fell off and hastily retreated. Years later he returned with Lyle Closs and found that during his absence someone had drilled up beside the crack. These were no ordinary bolts, but ones of doorknob dimensions. Undaunted, they pressed on, climbing the route free at about 20, slinging the doorknobs en route.

Nobody has ever admitted responsibility for this work of megabolting, but since there is an army base atop North Head it is reasonable to assume that little green men with blackened faces, under cloak of darkness drilled silently through the night to raid the deserted car-park. But the piece de resistance of the Head lies just round the corner from The Bolt Route, sheltered by two overlapping 13 metre roofs. Claw had discovered it from below and severely inspected it from above. He billed the route as the worst and most horrendous yet, thus leaving no choice in the matter of its ascent.

Claw established a first pitch up a shallow corner groove to a stance to one side of a huge roof and beneath another. The holds were rounded and covered in a ball-bearing-like mixture of salt and sand, lending a great insecurity to the moves. Try as we might, no amount of chalk would amalgamate these substances. At the stance I found a veritable Maestri-load of bolts studded about me.

Our third member, my brother Glenn, who had never touched rock before, came up, utilizing every piece of protection, showing great potential and originality of technique. The next pitch traversed some cheesy stuff. I placed another bolt for a hand-hold with the mutant crag hammer. (Its head had snapped in two during the frenetic bolterama of the siege of Grand Mal and it had been repaired and remodelled, with nuts and lumps of steel for extra weight. A piece of welding rod, fused to the pick gave it the curious appearance of having antennae.) Clutching the steel carrot I completed the traverse and arrived at a solid diving board of rock at the lip of both roofs.

Glenn excelled once more, grinning in the face of complete horror – such is the advantage of total unfamiliarity. But alas, on the last pitch his ability to ascend evaporated and he hung in space like a dismal sack of potatoes till we bodily hauled him over the top. Ascended in the manner of true foxes. My brother and I had even named the route before we reached the top Honour Thy Father, (22 M1). We have our reasons why.

The truth is that the sea cliffs gradually took control of our minds. What began as our naive manipulation of them into a covert little art statement ended in an obsession such that we could rarely leave the city. We were at the beck and call of the sea cliffs. We washed grains of them out of our hair at night in the shower and woke up in the morning to find sand in the sheets. Aha! Sleeping with the sea cliffs again, eh?

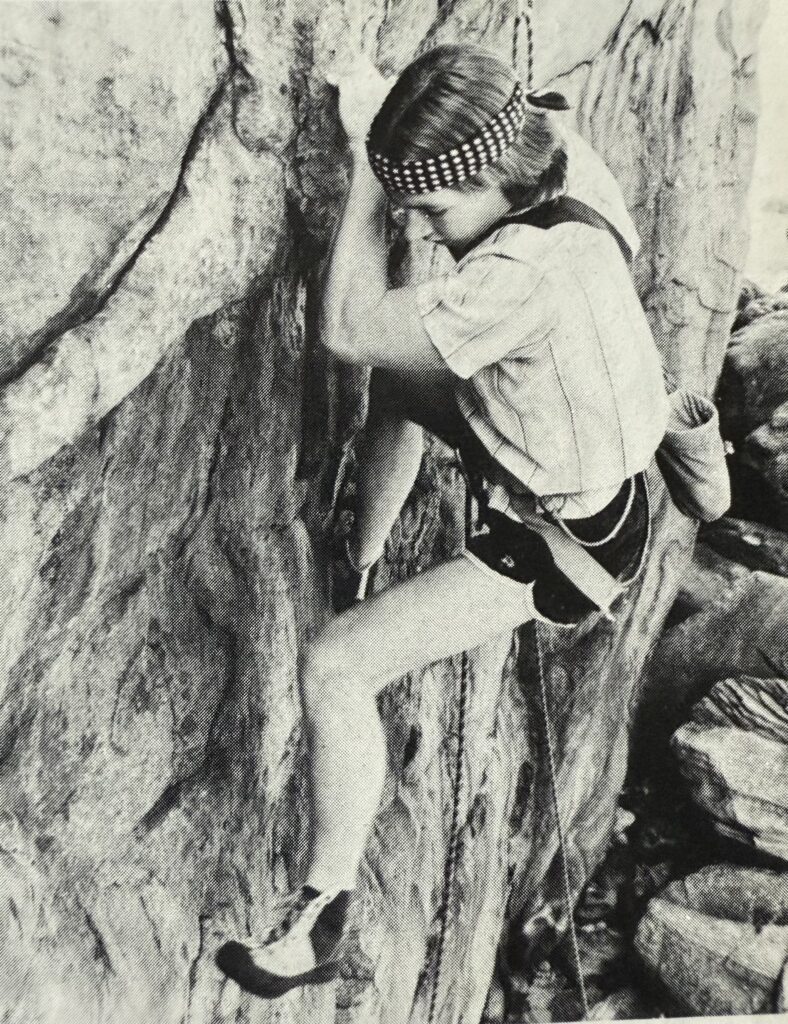

Left: Rock Editor Chris Baxter shakes his way up The Bolt Ladder (20) with this astounding megavolts. Right: Warwick Baird at grips with Surrogate Sickle (21) Glenn Robbins

Exploring again, on the legendary Ducati, we passed oil refineries and the archaic silhouette of the Bunnerong Power Station. The old sand dunes that once drifted free and aimlessly have been immobilized under a bright green coating of spray-on tar. They shall rove no more on the sacred autobahn.

We parked in front of some deserted dark brick shoe box and descended to the sea. What’s this? A bolt? Sure enough, in the middle of a featureless face was a bolt. Beside it another, and above it yet another. In fact every metre on every conceivable section of rock grew a little flower of steel. As we gazed in awe at this amazing sight I stubbed my toe on…egad! another bolt no less, at my very feet. The whole bay is abristle with bolts, rivets and nails. Who could be responsible for such a mad act? Who can we blame? Names, give us names. And then we realize where we are. Of course, Christo’s wrapping of Little Bay!

A few years ago a fellow by the name of Christo, who fancied himself as a bit of an avante garde artist, decided to sell the sea cliffs as art on a grand scale. He literally wrapped Little Bay up in thousands of metres of plastic sheeting, rivetting it to the cliffs and wave platform, creating a ghostly billowing work. No doubt Christo and his cronies viewed their creation from a distance, sitting in a boat toasting the thing with champagne. ‘Here’s to strangeness’, they may have said as they raised their glasses on the pitching deck.

It only lasted a few days till it was ripped to shreds by a storm, but nevertheless Christo made his mark on the sea cliffs in a big way, and beat us at our own game. But what is art? Or more to our point, is climbing art? Is this thing that we do some graceful ballet, or is it just an oafish lunge, a sort of physical doodle on rock? And what about each different route? No two are alike, each has its own colour and texture, demands a certain pattern of moves and may even evoke its own special emotional or psychological state. While some routes may be a casual stroll that appeal to the lighter mood of the artist, others are an intense personal struggle painted with sweat, fear, even blood. Others appear as an outrage that no one comprehends at all.

Each is sculpted uniquely; fine grained, rough hewn, detailed or polished smooth, man sized or monolithic. And each feature – what does it mean, if anything at all? What meaning has this loud, wide slash in the canvas, this shiny blank slab? What do we see behind this delicate finger-traverse or this all-conclusive impassable roof? Then there is the question of the climb’s name. Is this not also part of the work, the embodiment of some artist’s mind? Or are these names simply labels for supermarket convenience? Moreover would it be possible for climber’s collection of ascents and see something of that individual’s personality mirrored in them? Long strokes between protection or dashes into unconventional territory could show something of the workings of a mind. And the physical presence; an overhanging crack may tell of a strong hand, while a thin face may imply a more nimble touch.

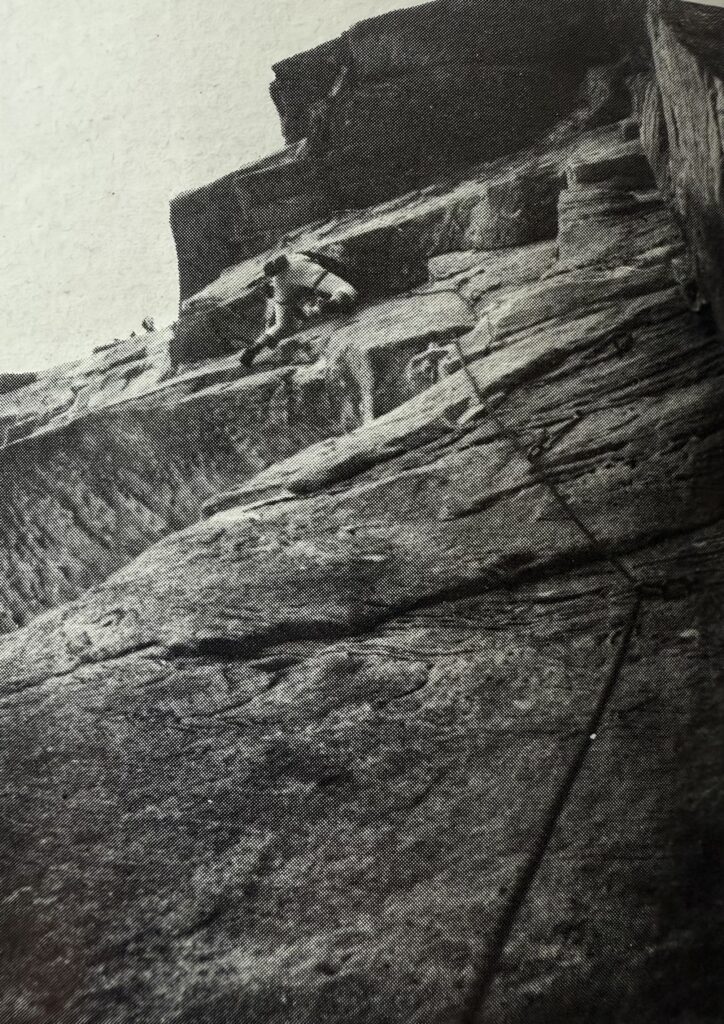

Left: Two views of The Fear (17). Mike Law emerging from the roofs on to the final wall. Right: The top pitch more or less follows the arete above the belayer.

Could these rocks touched by human hands reflect a consciousness, a period, an opinion, as evidenced by a language of movement and shape and style akin to the language that we gauge the statements made by art today? Or is it we who are governed by the rock, told where to go – we as the medium of the rock and not the rock as our medium. Or is it that we just can’t draw? Whatever the case, it’s a strange dance we do out here on the perimeter; a strange dance indeed.

Just beneath the rambling neglect of the Waverly cemetery, another shore-front field of flotsam and lost dreams, of a different kind, lies the last cliff to be mentioned in this handbook. Small and solid, an exception to the rule of pure rubbish, its wave platform is littered with the smashed marble headstones turfed off by ghouls and grave robbers. At the base of the classic Bondi Mail Sorter lies a fragment of tombstone that reads ‘Loving Mother’. The Mail Sorter (22), is a flared crack through a sizeable roof, reminiscent of an Arapiles classic, Kama Sutra, though slightly softer. To its right, marked by a headless Madonna, lies a short but excellent face problem named Poste Haste (20), a gritsone-like route ascended on solution pockets.

Claw and I are cruising about in the mid-winter sun, mopping up a few last problems before I leave for Amerika, a long lead-out that is another story altogether. In some ways it seems the only escape from this senseless life of sea cliffing. We are sitting on a cornerstone that marks the north-east boundary of the cemetery, atop the grey Poste Haste. Behind us sprawl acres of tombstones, tilted every which way, dormant under a thick blanket of grass and the occasional dandelion. And on every stone a little verse so similar to the one next to it that there is scarcely any difference between them. A field of faceless stones all saying the same thing, as if we were all as alike in life as in death. It isn’t as simple as that. I look at the owl-like eyes beneath Claw’s shock of red hair and decide that, no, we are not all alike. It is the differences between us that make any association worthwhile.

‘Well Claw, would you care for me to compose your epitaph for you today?’

‘Why certainly do go on.’

‘Let’s see… how about… “Mike Law; The Inventor of the Sydney Sea Cliffs”…or maybe… “Mike Law; so sensitive was he to the dimensions of nonsense, he got inside this concept and was looking out.”’

‘Hmm… very nice.’

It was one of those incredibly clear and windless winter days where the sea laps tamely at the cliffs and the sun seeps into your body. We just sat there, facing the Pacific, too lazy to even coil the rope at our feet.

‘You know Java, we should write something about these sea cliffs some day.’

‘Ah… it would have no commercial value whatsoever.’ I reply.

‘Precisely. Let’s do it anyway.’

The sea was calm, almost like a mill-pond..

So what is there? Not all that many climbs or big numbers in the grades, but climbing there seems to involve a far greater concentration of all the emotions that commonly make up climbing. Each cliff, whilst recognizably sea cliffing, is quite distinct in its climbs, chaos and rock. From the short intense problems and good rock of Bronte and Rosa Gully to the big ones of The Gap and the horror of North Head, they only share the same sea. The most southerly cliff is Bronte, idyllically nestled below Waverly cemetery! A small crag of excellent rock, sprinkled with random pockets.

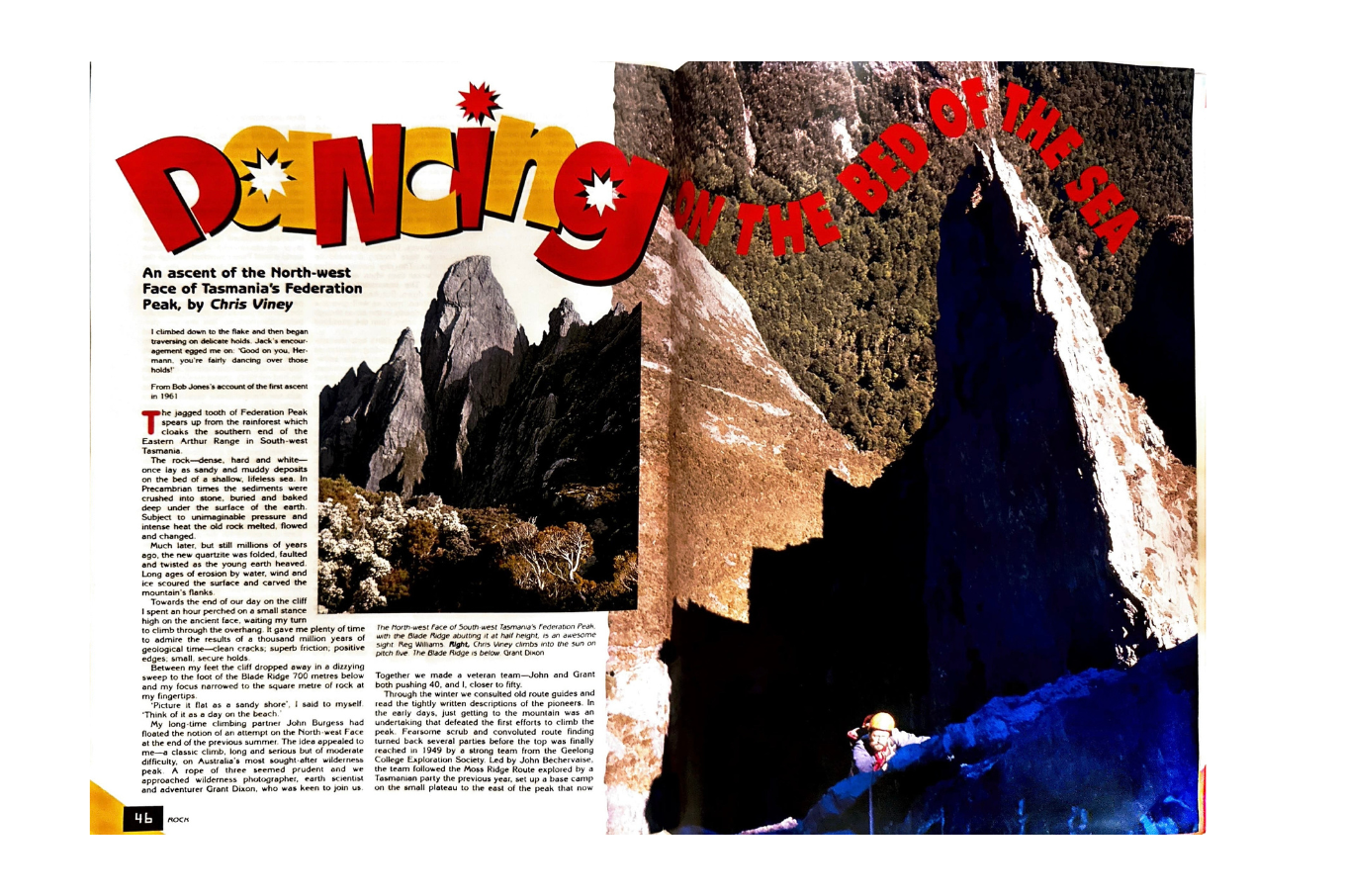

Approach is from the south. The Mail Sorter (22) is the only real line on the cliff, a six metre roof with a finger-crack splitting it; v des unless you’re a locks/layback whiz. Left of the Mail Sorter a two metre root runs along the cliff for six metres; Flexitime (22) gains the lip and then hand-traverses along on big rounds to a hard exit – most pumpy. Thirty metres right of The Mail Sorter is a black undercut arete that Greg Child and I played on until it became a climb, Poste Haste (21). A very pleasant little unit. Just left exists Wrinkle City, a trick 20.

Hop on a bike (motorcycles are a necessary accoutrement to climbing here for fast retreats and to whip one into the appropriate adrenalin-sodden state) and lash a victim on with the climbing gear. Three kilometres north past Bondi Beach and a few fine cake shops, continue on foot across the golf course, a small and sociological extension of modern physics (“We then subjeckted der two human units to 28 GeV of golf balls and high frequency technobabble, serious degeneration was noted…).

Still reeling after the white bombardment fall unawares down the Black Filth Couloir. On the south side of the gully, at the base, is a short chimney with a thin crack on the right wall. Arapiles (18) does a few moves up the chimney and then blasts up the crack; quite a classic. Thirty metres left is an impressive wall of steep orange rock, looking solid and quite modern in its possibilities. Indecision about including Grand Mal as a good route, and ambivalence about repeating it, force me to consider it as significant at least. Imagine Arapiles rock that bursts under body weight as though from trauma, from which its bolts (about 13) flex and ooze wearily and runners explode from their gem-like settings.

The rock forces upon you two swinging hand-traverses. One rises at 45° and is six metres long. Greg and I used it as a stepping-off point from parties and hangovers, tried it a few times before we finally got up it, 22, 23, 24?

Two kilometres north is Rosa Gully (seen on most road maps as Diamond Bay). It is actually two gullies, the north being worthwhile. An easy scramble down past the usual rubbish. Rising from the detritus is a very steep south wall that at present has only two horrible and mediocre routes best forgotten. Opposite is a thin line that may have been aided once in days of iron; it is now Surrogate Sycle (21), another excellent toy. Thin laybacking and face climbing leading to a crack. Just left of SS is a minor test piece, Chance and Necessity (23), most tenuous, two bolt runners. (Be warned, it’s at least 20° steeper than it looks.) On the right of SS is Trick City (24), possibly the hardest route around Sydney, a well protected one-move problem. It has been called the first Post Modern climb (by whom?).

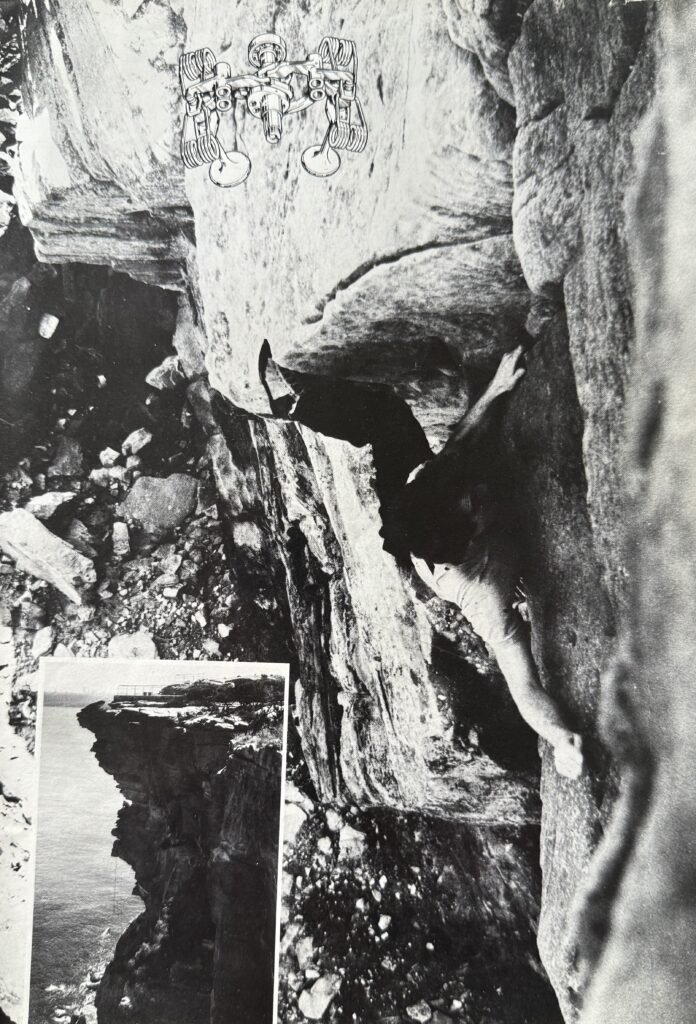

Left: Law again wrestling with Plunging Necklines (22), on the first ascent. Right: Law posing for his fans on the exit from The Fear (17). Gairns & Baxter

Walking north 30 metres round the arete brings Posturing (21) to hand, a big undercut arete starting 12 metres up. A jump and brisk hand-traverse out over space to the first bolt, clipped with a quickdraw and bated breath. The belay at the base of the next pitch needs another bolt. Pitch two is excellent; wide, exposed bridging. This route takes in some of the best positions known to Sydneysiders (supine excepted). Another 13 metres round the arete gets us to the start of the second pitch of Obscurity (19), a big, thin, rotting flake forming most of the third pitch; laybacking up vertiginous nonsense. This will incite very little interest in the hard lads who have just arrived; they’re here to do A Certain Flair (23). Obscurity’s direct start and a pumpy thin crack that overhangs a bit.

Further north of all this stuff (about 50 metres) is a single vague break through a bulge that guards most of this section. Karen (15) is the easiest route by the sea. A hard start and a long traverse make it a bit much for most beginners. A few miles to trendy old Watson’s Bay and parking at The Gap, a devastating 20 metre walk brings us to the cliff itself. From the look-out the north wall of The Gap faces us, looking quiet and maybe vertical. Unfortunately it overhangs some ten metres in its 40 metres height. In the middle of the wall a rightwards leaning corner, Cruise or Bruise (20), is an excellent introduction to the world of nonsense. A somewhat intense start past a bolt is followed by a long laybacking and bridging corner, perfect for the ageing (19 plus) sea cliff trendy. A traverse off right is preferable to the second pitch. Twenty-five metres right of this, round the arete, lurks an innocuous white corner capped by a big roof. Big Dipper (24) is an area test piece, especially as any hesitation or slip from the crux involves wetting oneself, if only in the ocean. (In fact doctors in the area, notably Mal Johnson, document a pre-dipper hysteria.)

The wall left of Cruise or Bruise becomes steeper, the holds smaller and the cracks scarcer. The first line is Snivelling Grooves (22). The first pitch is just a bit of technobabble past a bolt or two leading to an undercling that is quite wild. From the belay the second pitch looks quite peaceful, an easy-looking ramp followed by a small roof above a slab. Well, everything is 20° steeper than appearances: there is difficulty in just staying on the ramp, let alone oozing up it. The slab beneath the roof is frictionless and vertical and the two bolt runners seem only marginally stronger than the double ropes. Technology and security seem no longer compatible. Fortunately Greg led this pitch the first time. Above the roof the climbing is a long committing wall; good rests and runners every five metres. Tops.

Just left of SG a slight corner roofs itself in at six metres. Oblique Stress (23) starts up here. Solo up to two bolts, insecure face climbing out below the roof and a tenuous layback round the lip gets a large spike between your hands. The crack above is steep and hard to exit from. From the belay (four bolts, semi-hanging) a short traverse right gains a very steep crack, big holds beside it lead up a 45° overhung arete and by the time the angle eased back to vertical I was already irredeemably pumped. Found a rest that only served to worsen the situation, till I was forced to climb on or/and fall. Through one more bulge, past a bolt (placed on the second ascent) and a mantel shelf on to an easy slab (phew). The last pitch is horrendous but secure, a steep hand-crack that lurches out into space, traditionally led by Giles Bradbury.

On the south side of The Gap the cliffs tend to have few continuous or longer routes. They mainly finish on a half-way ledge or abseil in to start. Swing Time (21), a classic on huge buckets, starts by leaping off a boulder in the small cove some 80 metres south of Cruise or Bruise. Ten metres right, just left of the arete, is a thin crack starting round a roof. Jen’s Climb is really hard for one move just off the ground and past a bolt; probably 23, very nice. The other two routes that are excellent and fashionable around here are one pitch affairs that start half-way up the crag. Poet’s Corner (20) is a pure corner of orange rock, almost vertical, almost holdless, with a Stopper seam running up it. All very pleasant and safe with one absurd move half-way up. To get to it, walk about 60 metres south of the main look-out and look for a thin corner about two metres from the fence. A 20 metre abseil gets you there. Take a few brackets.

Ah me salty boy-o’s, this brings us to Lost in Space (17), arr matey, keel haul the parrot. Yes indeed, my boys, this one separates the land-lubbers from the chicken suckers. About ten metres south of the abseil point for Poet’s Corner is a little descent. Wander down for ten metres then abseil down a short corner and traverse right under the roof to a bolt belay. The route makes its way, the four metre roof above, via a devious heel-hook move. The roof is similar to Kachoong at Mt Arapiles, but the flake slopes drastically and inspires much darkness in the hearts of belayers.

After dicing with death and heart conditions the heel-hook and the jug are both attained. Strange stuff gets you to the next bolt and a rest, finish up the right arete, 17 eh.

North Head; ‘worthless nonsense’ was Greg Child’s diagnosis, but after climbing on it for some time this opinion was modified and I for one now firmly believe it to be nonsense laid down horizontally and hardened till it was firm enough to form roofs. At this point the whole mass was made vertical and erosion let in.

Most of it is less than good, low angle rubbish, but under the look-out are some classics: Honour Thy Father (22), Destroy All Monsters (20) (pitch one is an excellent direct start to The Fear). The Fear (17), The Bolt Route (20) All steep and horrendous in varying degrees, the latter three are even protected, very modern and spacious’. Right of this area of relative stability lurk a few esoteric ones, like Scrabble, fairly bland apart from poor protection. Around the point the cliff faces NZ and possibly in deference to our eastern companions there are even a few easy, pleasant climbs, almost (On the sea cliffs ‘easy’ generally implies low angle horror.) There is a small artillery emplacement half-way up and WW3 (15) meanders up to it and walks about six metres left before hand-traversing into a crack to finish. Albatrocity (18) follows a short finger-crack right of WW3 before rambling on to the gun emplacement. After repelling a few inscrutable little men, hop left a metre and trick a short corner. Climb diagonally right up aretes and walls to a bolt, head diagonally right to an exposed conclusion with an undercling flake; all very nice.

The traditional and hysterical reluctance of climbers to be pushed out into the very maw of disaster was only broken, in more recent months, by an arduous psychological campaign and threats of physical mishap. Mal Johnson’s closely consecutive ascents of The Bolt Route forced a few ferrety heads to turn and they advanced on the base of the route like mice stalking an edible time-bomb. Certain horrendous episodes still occurred, but they could be attributed to more ‘normal’ disasters such as 30 metre waves or entire cliffs crashing into the sea than the nameless and well-known fear. Suddenly every route was repeated thrice and the empire struck back.

By Cute Energy and Swing Time there exists a stepped overhung buttress split by a finger-crack Named, for no obvious reason, Life Jacket Chimney (ha ha 24), it was guarded by a sea at the base that dampened the spirits of many young jamBers. The second barrier was a two metre roof that is, I think, still unrepeated. Warwick Baird made the route the black edifice it is.

Giles Bradbury and I emerged on top of an area of cliff that looked as though it had just lost a genetic war, babbling about 20 metre run-outs and grade 24 cranks, to bag the aptly named Housemaid’s Knee. What prompted this foray into space, sand and madness was our recent success on the nearby cliff-splitter known as Quentin’s Climb (referred to as ‘Trendies Corner’ by the bitter and twisted). Six pitches and 110 metres long, it is the ideal one-day route. The first ascent was a pump with some 21 bolts being placed from various compromising positions, but it should achieve classic status by its thirteenth ascent. Oh yes, grade 20/21 (revised standard sea cliff grading).

On North Head I battled with my soul for three days before I could commit myself to cut loose on the lip of Plunging Necklines, a fine position with, as yet, no coronaries recorded. Three pitches of 22, the last a little more exposed than most. While any subjective dangers were played down by the sea cliff glitterati, the Camp Cove discoveries let loose a major moral danger upon the muscled youngsters. Walking past the more mundane tits and bums and rounding the point we reach simultaneously a small cliff and a large gay erogenous zone. Routes such as Gayline (22) and Strange Bedfellows (23 M1) are minor classics and routes often end belayed to a raincoated and bug-eyed pedarist or worse. The latent desires of the new wave have made this cliff a must.

Of course the best routes still await ascension, bolting into submission, chalking into some definition or merely climbing into the hearts of millions. Some contend that the sea cliffs are OK because they’re so close to the city (like a wine that is fine at 50 cents a flagon, but undrinkable at 60). These cliffs are no substitute or training ground. In comparison it is the established classics and popular climbs on ‘real’ cliffs that look a little pale. The sea cliffs pander to the need to be terrified or strong. Everything may look grim but if you take a bunch of laughs and a handful of brackets they can be a real giggle..