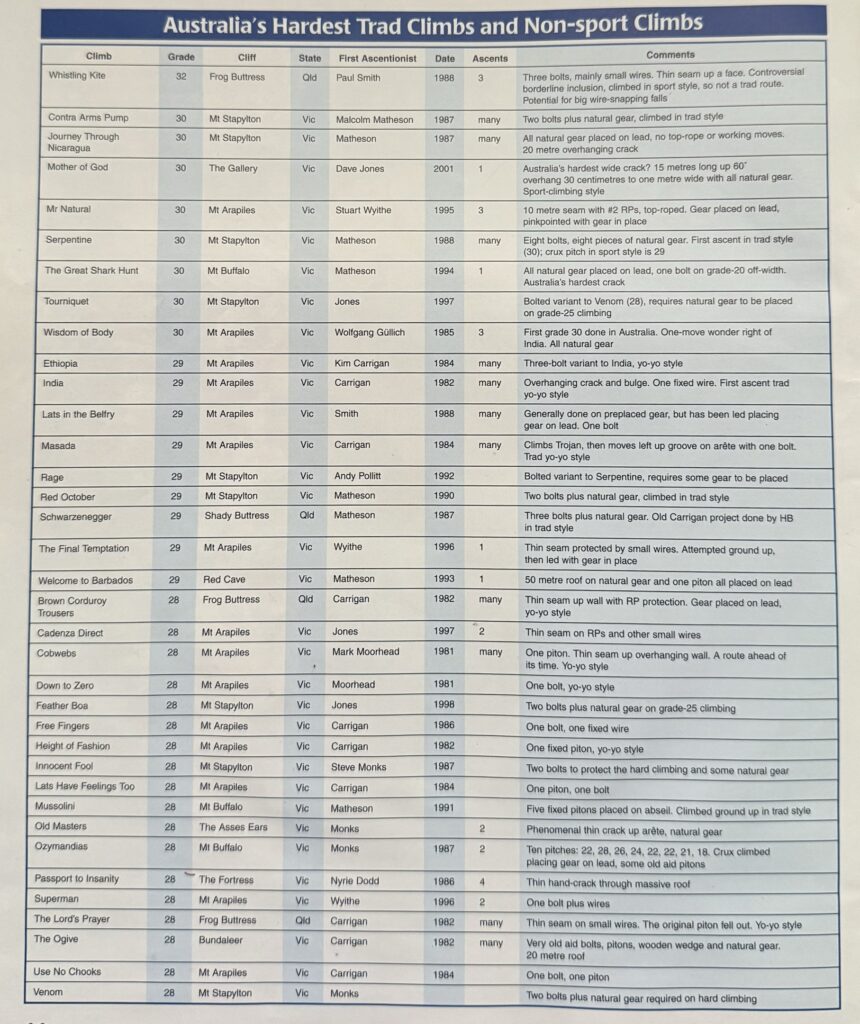

Australia's Hardest Trad Climbs

This article set out to define Australia’s hardest traditional climbs—a task as complex as the routes themselves. Exploring what makes a climb truly “trad,” it captures a moment in time when style, purity, and progression shaped the sharp end of Australian climbing.

Written by Gerry Narkowics

This article was originally published in Rock Magazine in 2002. The information, route descriptions, and access details reflect the conditions and ethics of that time. Climbing areas and their access arrangements may have changed significantly since then. Please consult up-to-date local sources, land managers, or climbing access organisations before visiting any of the locations mentioned.

Defining the hardest trad climbs in Australia is not an easy process. The use of natural gear on a particular climb doesn’t automatically make it traditional. The key issue is style—how the route was climbed. Style is at the very core of climbing; it’s why Reinhold Messner soloed Mt Everest without oxygen. He wanted the ultimate style. It’s why gritstone climbers in the UK risk life and limb. Clarifying style is important because without an absolute standard, we can’t be honest with ourselves about our climbs.

I see a continuum between trad and sport style. The ultimate in trad style is soloing. The next point is onsight climbing without falls and all natural gear should be placed on lead. Traditional style means lowering off immediately when you take a fall, without working the next move or placing the next piece. When you are back at the start of the climb, you should pull the rope from the protection. The Great Shark Hunt (30) by Malcolm Matheson (‘HB’) is the hardest route that has been climbed in this style in Australia. It is an overhanging, flared, diagonal crack with poor jams, single-digit finger-locks and technical footwork.

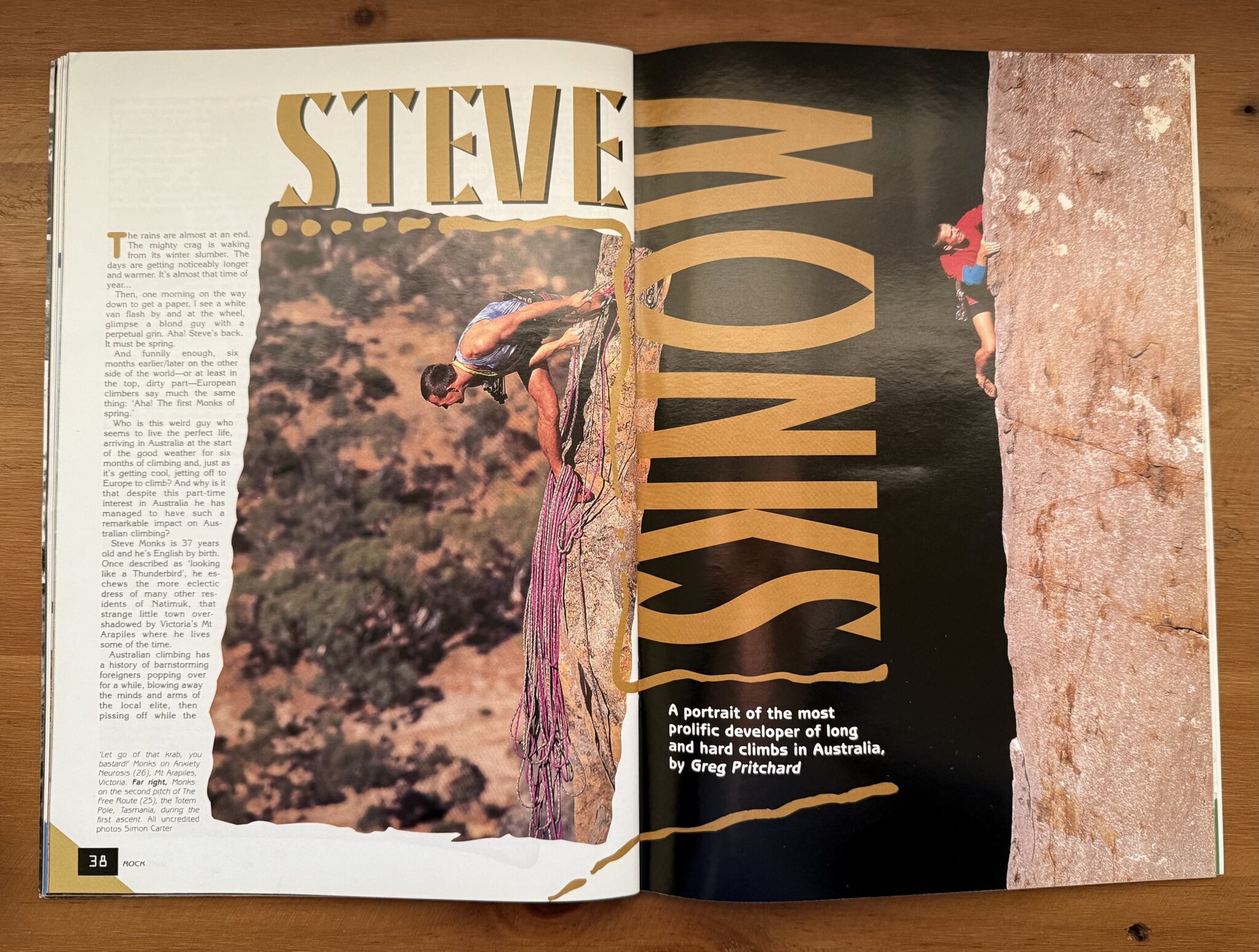

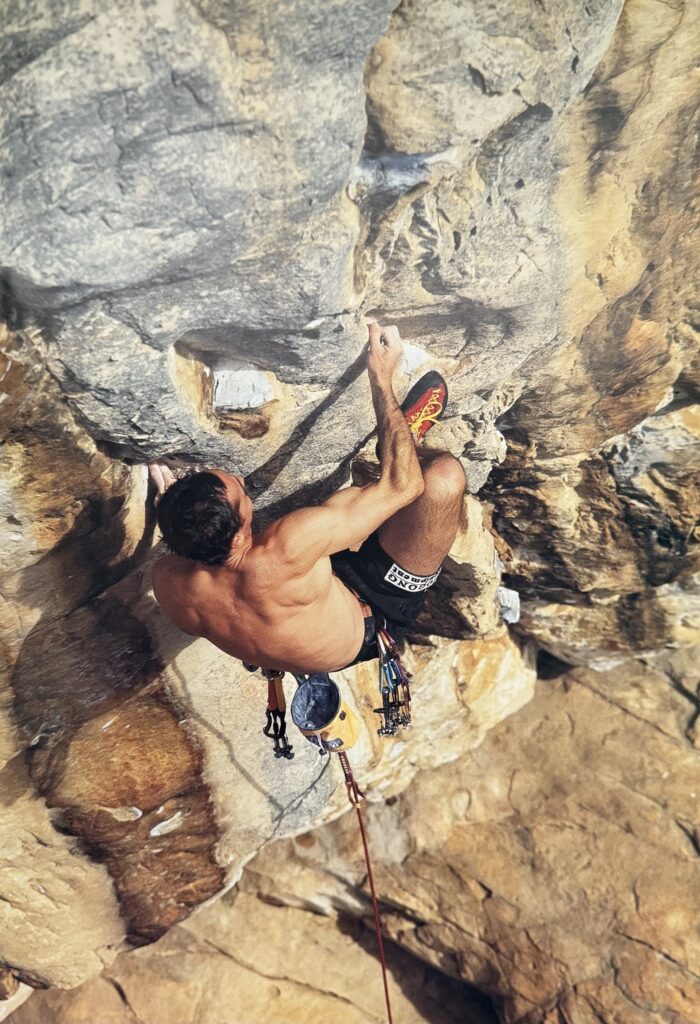

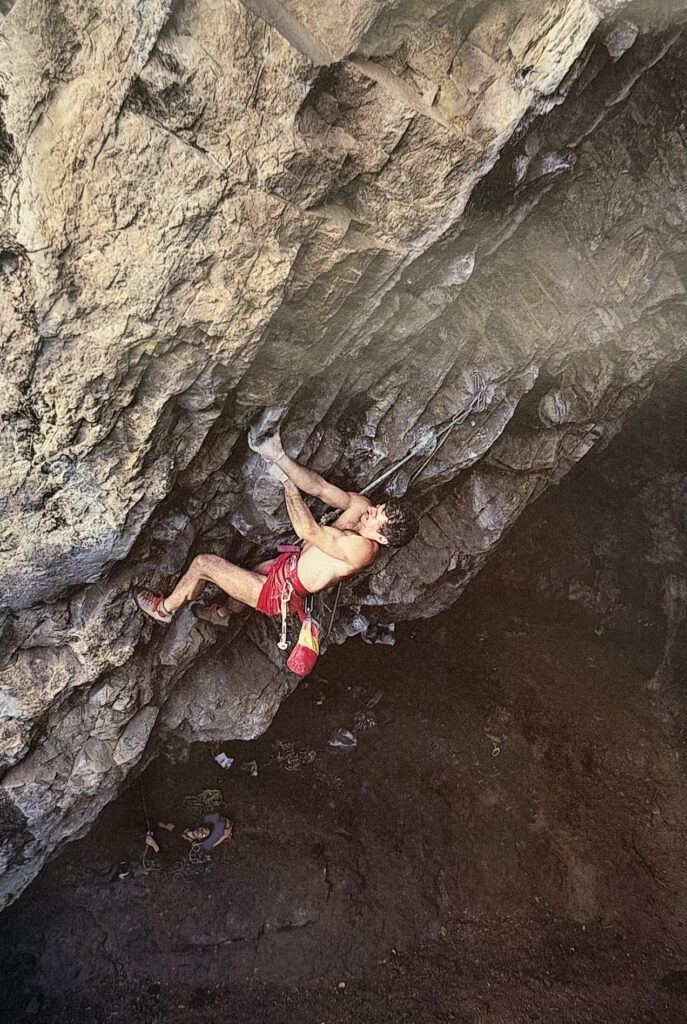

Left: Malcolm Matheson CHB belayed by Jon Muir on his most famous offering, the exquisite and highly sought-after Serpentine (30), Mt Stapylton. Image by Glenn Robbins Right: Kim Carrigan on the historic first ascent of India (29), Mt Arapiles, Victoria, in 1982. Image by Chris Baxter.

The next point on the continuum is a mixed-protection route on which natural gear is used in combination with minimal fixed gear such as bolts, pitons and fixed wires. Strictly speaking, fixed gear disqualifies the route from the true definition of traditional style, but mixed-gear routes can still be climbed in trad style. Serpentine (30) has eight bolts and eight pieces of natural gear. HB did the first ascent in traditional style and graded it 31. There have been very few repeats of the scary grade-24 first pitch. Most would-be ascentionists preplace gear on the second pitch and redpoint it as a grade-29 clip-up, but to climb the whole route in traditional style is much harder.

In the 1980s many routes were climbed in yo-yo style; climbers would be lowered off after a fall but would leave the rope clipped to the high point to climb with a top-rope for the next attempt. This is a more challenging style than a preworked redpoint because the next moves and runner placements after the high point remain unknown.

The next point along the continuum is a route on which all natural gear or mixed protection is used in sport style. This means top-roping the climb, preplacing the natural gear, working any difficult moves between runners and then leading the climb, clipping preplaced draws. The only traditional thing about the ascent is the natural gear, not the style. Dave Jones’s first ascent of his phenomenal route Mother of God (30) is an example of this style. A candidate for one of the hardest off-widths in the world, it is a 15 metre crack between 30 centimetres and one metre wide on a 60° overhang.

Jones attempted to climb it from the ground up and worked the moves to the top, placing gear as he went. The gear was in place for the redpoint. Strict trad style would have dictated that he lower off after each fall and place the gear on the lead attempt. The dangerous UK gritstone routes fall into this category. They are not sport routes because of the diabolical gear placements required, but gear is generally preplaced and the lead (head point) is usually attempted after extensive top-rope rehearsal. The styles closer to the pure trad end of the continuum are more difficult and challenging.

Several climbers have emerged as the major players in hard, traditional climbing. In the late 1970s and early 1980s Mark Moorhead was at the cutting edge, putting up Cobwebs (28), which was then one of the world’s hardest routes. Kim Carrigan pushed the boundaries of trad climbing to the limit during that era. His hardest all-natural-gear route was Brown Corduroy Trousers (28) at Frog Buttress, Queensland. India (29) and Masada (29), both at Mt Arapiles, Victoria, are not sport routes because of the natural protection used to climb them, but both were put up in sport style. Carrigan preplaced a #3 RP on India, and worked the crux from that piece. Freeing old aid routes was one of Carrigan’s missions, the hardest being The Ogive (28), a 20 metre roof at Bundaleer, in the Grampians, Victoria, with some natural gear, as well as manky aid bolts, pitons and a wooden wedge. In the late 1980s and early 1990s HB and Steve Monks took up the mantle of hard trad climbing.

One of Monks’s finest efforts was a free ascent of Ozymandias (28, formerly M5) at Mt Buffalo, Victoria; he led the crux pitch almost entirely on RPs. HB is the greatest exponent of traditional climbing Australia

has ever had. Journey Through Nicaragua (30) at Mt Stapylton, Victoria, is a 20 metre overhanging crack with protection well below your feet on the gnarly, finger-locking crux. Matheson climbed Nicaragua from the ground up placing all natural gear on lead, lowering and pulling the ropes after every fall, without working moves or higher runner placements. Welcome to Barbados (29), a 50 metre roof at Red Cave in the Grampians, was also done in impressive style. Matheson climbed from the ground up and onsight, placing natural gear and working the moves. He removed the gear and tried to lead it the next day but failed. He returned six weeks later with the gear racked in order, and led it successfully on his first attempt.

In the mid 1990s Stuart Wyithe put up some desperate new trad routes in good style such as Mr Natural (30) and The Final Temptation (29), both at Mt Arapiles and both examples of climbs on thin seams protected entirely by small wires. From the late 1990s to the present day, Dave Jones and Chris Jones have been exploring the limits of hard trad climbing. Both have repeated many of the climbs on the list, added their own test-pieces and climbed UK gritstone horrors up to E8 (31/32).

There are 12 all-natural-gear routes of grades 28 and above in Australia; only four of them are true cracks (The Great Shark Hunt, Journey Through Nicaragua, Mother of God and Passport to Insanity).

Apart from two roof climbs, the majority are thin seams and face-climbs protected by wires and minimal fixed gear. Mt Arapiles and the Grampians have contributed the bulk of hard traditional routes and a few are at Mt Buffalo and Frog Buttress. These crags lend themselves to hard natural-gear routes more than

almost any others in Australia. They are steep and the rock accepts good nut placements. The key players were also based in Victoria. Some of the borderline inclusions are Whistling Kite, Ethiopia and Rage but they each have enough natural gear to fall inside the ‘trad’ category. Other borderline contenders include Height of Fashion, Free Fingers and Use No Chooks which are essentially boulder problems beside a piton or bolt.

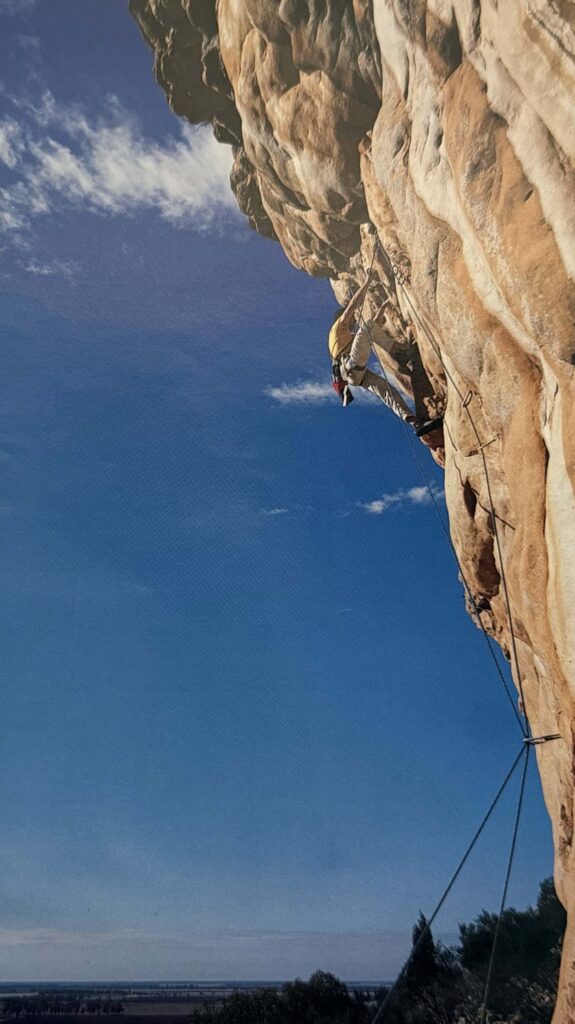

Left: This classic photo of Athol Whimp gives a good idea of why Contra Arms Pump (30), Mt Stapylton, the Grampians, Victoria, is one of our hardest trad routes. Image by Matt Darby Right: No contest: the legendary HB again, this time grappling with Schwarzenegger (29), Shady Buttress, Queensland, for the first ascent. Image by Glenn Robbins

In conclusion, people can climb hard routes in whichever style they choose. Do it trad style, sport style or in-between style. Tick a red point, pink point or a head point; you can yo-yo it, top-rope it or even aid it, as long as you’re happy with that style. The option to improve is always there.

Thanks to Malcolm Matheson, Dave Jones, Kim Carrigan, Mike Law, Simon Mentz and Greg Pritchard, without whose help this article could not have been written.

Gerry Narkowicz

has been climbing for more than 20 years, mainly in the Launceston area of northern Tasmania. He has taken part in the first ascent of more than 600 routes.

Two decades on, the landscape of Australian trad climbing has evolved—but the question remains: what defines the hardest climbs today? If this list were rewritten in 2025, which routes would make the cut? Join the conversation on our socials and let us know which lines you believe deserve a place among Australia’s modern trad test pieces.

Other articles: ARAPILES’ HARDEST CLIMBS