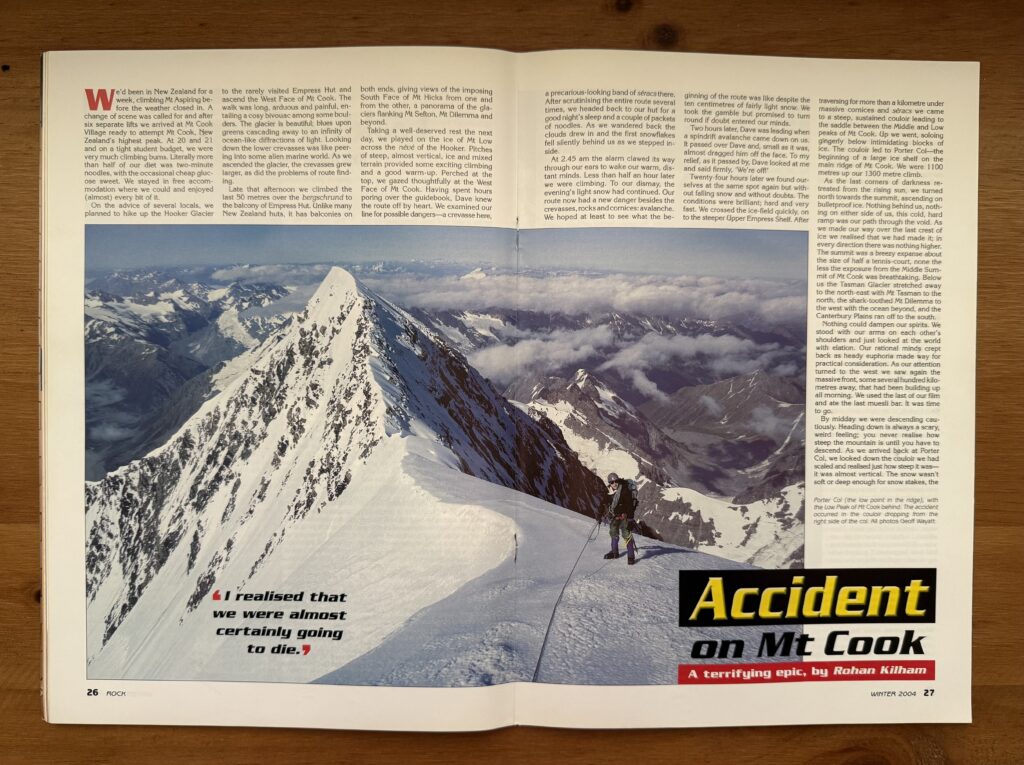

Accident on Mt Cook

Originally published in 2004, Accident at Mt Cook recounts a harrowing climb on New Zealand’s highest peak. Rohan Kilham’s first-hand account captures the thrills, dangers, and near-tragic misadventures of a young climbing duo navigating glaciers, icefalls, and avalanches. More than a decade later, the story still resonates as a testament to endurance, skill, and sheer luck on the mountains.

A harrowing near-death experience on New Zealand’s highest peak. Rohan Kilham recounts the terrifying fall, injuries, and dramatic rescue on Mt Cook, capturing the beauty, danger, and sheer unpredictability of alpine climbing.

We’d been in New Zealand for a week, climbing Mt Aspiring before the weather closed in. A change of scene was called for and after six separate lifts we arrived at Mt Cook Village ready to attempt Mt Cook, New Zealand’s highest peak. At 20 and 21 and on a tight student budget, we were very much climbing bums. Literally more than half of our diet was two-minute noodles, with the occasional cheap glucose sweet. We stayed in free accommodation where we could and enjoyed (almost) every bit of it.

On the advice of several locals, we planned to hike up the Hooker Glacier to the rarely visited Empress Hut and ascend the West Face of Mt Cook. The walk was long, arduous and painful, entailing a cosy bivouac among some boulders. The glacier is beautiful; blues upon greens cascading away to an infinity of ocean-like diffractions of light. Looking down the lower crevasses was like peering into some alien marine world. As we ascended the glacier, the crevasses grew larger, as did the problems of route finding.

Late that afternoon we climbed the last 50 metres over the bergschrund to the balcony of Empress Hut. Unlike many New Zealand huts, it has balconies on both ends, giving views of the imposing South Face of Mt Hicks from one and from the other, a panorama of the glaciers flanking Mt Sefton, Mt Dilemma and beyond.

Taking a well-deserved rest the next day, we played on the ice of Mt Low across the névé of the Hooker. Pitches of steep, almost vertical, ice and mixed terrain provided some exciting climbing and a good warm-up. Perched at the top, we gazed thoughtfully at the West Face of Mt Cook. Having spent hours poring over the guidebook, Dave knew the route off by heart. We examined our line for possible dangers—a crevasse here, a precarious-looking band of séracs there. After scrutinising the entire route several times, we headed back to our hut for a good night’s sleep and a couple of packets of noodles. As we wandered back the clouds drew in and the first snowflakes fell silently behind us as we stepped inside.

At 2.45 am the alarm clawed its way through our ears to wake our warm, distant minds. Less than half an hour later we were climbing. To our dismay, the evening’s light snow had continued. Our route now had a new danger besides the crevasses, rocks and cornices: avalanche. We hoped at least to see what the beginning of the route was like despite the ten centimetres of fairly light snow. We took the gamble but promised to turn round if doubt entered our minds.

Two hours later, Dave was leading when a spindrift avalanche came down on us. It passed over Dave and, small as it was, almost dragged him off the face. To my relief, as it passed by, Dave looked at me and said firmly, ‘We’re off!’

Twenty-four hours later we found ourselves at the same spot again but without falling snow and without doubts. The conditions were brilliant; hard and very fast. We crossed the ice-field quickly, on to the steeper Upper Empress Shelf. After traversing for more than a kilometre under massive cornices and séracs we came to a steep, sustained couloir leading to the saddle between the Middle and Low peaks of Mt Cook. Up we went, soloing gingerly below intimidating blocks of ice. The couloir led to Porter Col—the beginning of a large ice shelf on the main ridge of Mt Cook. We were 1100 metres up our 1300 metre climb.

As the last corners of darkness retreated from the rising sun, we turned north towards the summit, ascending on bulletproof ice. Nothing behind us, nothing on either side of us, this cold, hard ramp was our path through the void. As we made our way over the last crest of ice we realised that we had made it; in every direction there was nothing higher. The summit was a breezy expanse about the size of half a tennis-court, none the less the exposure from the Middle Summit of Mt Cook was breathtaking. Below us the Tasman Glacier stretched away to the north-east with Mt Tasman to the north, the shark-toothed Mt Dilemma to the west with the ocean beyond, and the Canterbury Plains ran off to the south.

Nothing could dampen our spirits. We stood with our arms on each other’s shoulders and just looked at the world with elation. Our rational minds crept back as heady euphoria made way for practical consideration. As our attention turned to the west we saw again the massive front, some several hundred kilometres away, that had been building up all morning. We used the last of our film and ate the last muesli bar. It was time to go.

By midday we were descending cautiously. Heading down is always a scary, weird feeling; you never realise how steep the mountain is until you have to descend. As we arrived back at Porter Col, we looked down the couloir we had scaled and realised just how steep it was—it was almost vertical. The snow wasn’t soft or deep enough for snow stakes, the ice not strong enough for screws and a hard, wind-blown layer of ice covered almost every rock, making it difficult to place gear in cracks. The only point on which to anchor our ropes was a large boulder sticking out of the ice. Dave gingerly weighted it to test whether it would break free, I did the same and we were both satisfied with its resilience. We set our ropes over the boulder and I went first as Dave anchored his ice-axes and clipped into the rope.

Approximately five metres down I heard an urgent shout and jerked my head up to look at Dave. My heart skipped at the strange sight above—Dave was twisted in some impossible contortion. There was no way he could balance like that; he wasn’t attached to the face of the mountain. Then I noticed that I wasn’t either. I felt my feet come away from the mountain, and then I noticed the looming boulder.

The world slowed for just a moment. The boulder seemed to float there before I realised what was about to happen. I didn’t have time to react, I fell like a rag doll backwards onto protruding rock. Dave, the boulder and I plummeted towards the world below.

I realised that we were almost certainly going to die. I reached for my ice-axe; if I didn’t self-arrest this was the end of us. We wouldn’t stop till we hit the ground, some 900 metres away and approaching rapidly. I twisted to the left, trying to get to the axe which was holstered in my climbing harness. I grabbed its head only to be knocked again by a sudden thud. I looked to my right, strangely calm after passing the point of panic. It was like watching a slow-motion film of a water slide. Dave was sliding on his back within arm’s reach of me, flopping around, then the boulder rumbled down between us. There was sliding and free fall for several more seconds. Then another look below revealed a drop into a crevasse. My last memory is of being flung at horrendous speed from the lip towards a patch of snow.

I was face down, unable to move, when I heard a chilling thud. Then silence. I didn’t know where we were, all I knew was that something bad had happened. I pushed with my hands against the snow and looked up to see Dave lying there, motionless and silent. For a second I was ready to panic—there was no pain, no reason, endorphins flooded my brain. I heard a moan. Dave! He sat up, seemingly unhurt. ‘Ro’, he murmured. I didn’t know what to say. We pulled closer to each other. ‘What happened, man?’ he asked. ‘I don’t know.’ ‘Where are we?’ ‘I don’t know.’ ‘Okay, I think I’m gonna need a minute just to get my head sorted here.’ ‘Sure’, I answered. ‘Me too.’ We hugged awkwardly and sat still.

After five minutes or so I realised that we had been climbing and thought that this might well be Mt Cook. ‘Wow!’ I thought, ‘We’re on Mt Cook.’ Things began to come back—it wasn’t that I remembered them, I just knew. As I told Dave, it all began to make sense and our predicament began to dawn on us. For 20 minutes or more we sat and talked about what had happened; how it had happened. My mind entered survival mode—remembered the weather, I wondered whether we could get to the hut. I asked Dave if he was hurt. His one complaint was that he had a sore head and was very tired. He wanted to sleep.

Dave had been knocked unconscious in the fall, his helmet was in pieces, and knowing what can happen to people with head injuries I was suddenly very alarmed. What if it was an epidural or sub-dural haematoma? I checked his vision, then the size of his pupils: they were a little dilated. Alarm bells began to ring. I almost yelled at him: ‘Dave, you can’t go to sleep. Dave, you’ve got to listen to me, this is very important. Dave, you can’t go to sleep.’

I probably didn’t have to tell him, I think he knew. Having assessed Dave, I began to examine myself for injuries. My head was okay, my legs and arms felt fine, my eyesight and coordination were perfect—my nose hurt, but I could live with a broken nose. We had to get back to the hut; the weather would come in by the end of the day and there was no way we wanted to be caught out in it. As I tried to stand, I felt pain shoot up my right leg and left ankle. My hip buckled, and I collapsed into a writhing mass in the snow.

I looked under my jacket to find a large, bulbous, purple mass across the right-hand-side of my abdomen. I couldn’t move my leg or upper body without excruciating pain. We agreed that Dave had to reach the radio at the hut and get help. He would have to solo some 800 vertical metres down to the hut over ground with reasonable avalanche danger, some short but steep down-climbing and an ice-field with considerable crevasses. I wanted to help but there was nothing I could do.

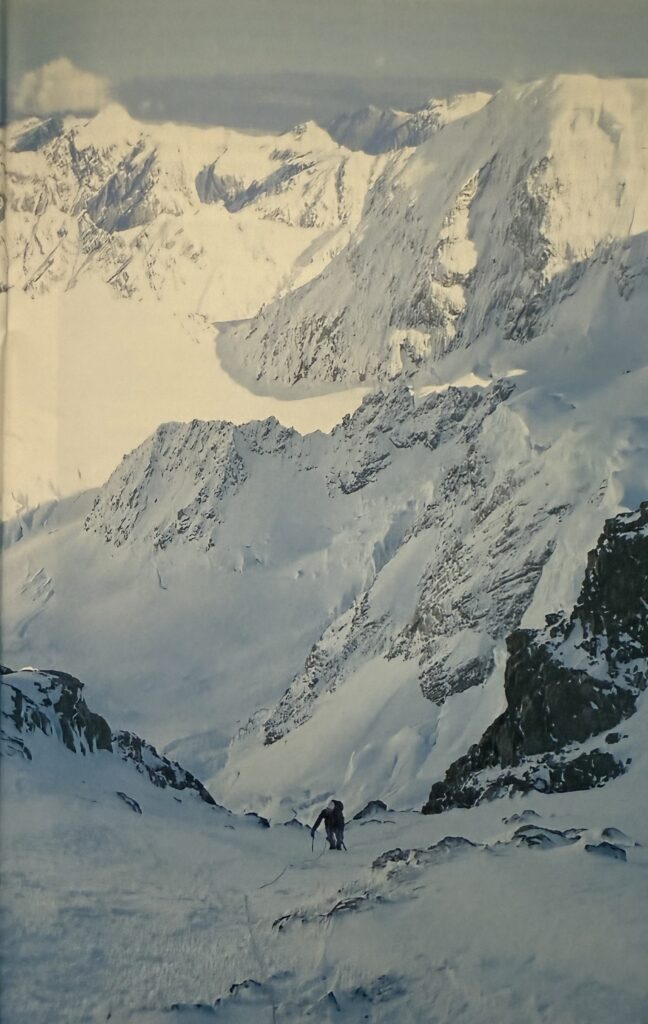

Scene of the fall: the couloir leading to Porter Col Mt Hicks Is behind on the right.

The ecstasy of an hour ago had been wrenched from me, replaced by a detached, depressed feeling as Dave turned to wave a weary goodbye. After a few minutes Dave disappeared behind a large block of ice. He reappeared later on a lower slope before finally disappearing behind the Upper Empress Shelf. He was moving very slowly; I estimated that without the accident we could have done the journey back from our position in less than an hour-and-a-half.

We needed to traverse the Upper Empress Shelf, descend the ice-field and then it was only 15 minutes round a large, rocky ridge to the hut. It was still a long way away—from where I sat it wasn’t visible and a person standing outside was only a black speck so small that you couldn’t see them move.

As I sat there, something stuck to my bottom lip; I took off my glove and put my hand to my mouth. My top lip stung a little as my fingertips probed it. Withdrawing my fingers I found that they were covered in blood. So, too, was my jacket. Blood had poured everywhere—my jacket was drenched to the waist on the inside. Blood had been trickling down my chin and into my mouth, the sweet, salty taste was everywhere. As I probed again at my mouth, I discovered that my top lip had a nasty gash starting from inside my mouth and spiralling all the way to the outside on the left-hand side of my mouth. My lip was almost severed but for a fleshy flap directly below my nose. It dangled down below my bottom lip, sticking to my face with every movement.

Two things worried me about this new discovery. The first was that Dave hadn’t noticed, and the second was that I hadn’t. If Dave hadn’t noticed it perhaps he was suffering the delayed effects of head trauma. I put this out of my mind and tried to concentrate on other things. I decided that if I hadn’t noticed this fairly large wound, there was a chance I hadn’t noticed others: it was time for a thorough check-up. I started with my head. Removing my helmet, I carefully applied pressure to my skull and neck and felt down my body checking for injuries. To my relief, my head and neck were fine. My pack’s x-shaped internal frame had supported my back wonderfully during the fall.

As I continued I was relieved to find few other injuries. However, my legs were a bit of a worry. I took off my salopettes for a better look. A crampon spike had penetrated my gaiters and Gore-Tex pants. The wound ran deep into the side of my calf but was clean and not too painful. The rest of my leg was a different story. Down the right-hand side of my abdomen to my belly button was a purple, yellow and brown sore and swollen mess. This continued round my side, into my hip, and down the back and inside of my right thigh to just below my knee. The pain was excruciating. The leg was swollen to one-and-a-half times the thickness of my other one, forcing my left leg out to one side. I deliberately didn’t look at my ankle. I couldn’t bend down to untie the laces, and I figured that it was best to try and minimise swelling with the pressure of my boot.

I decided that things weren’t that bad. The amount of blood that had leaked from my face and torn muscles was beginning to make me feel faint. To lift my blood pressure I ate the last of my sweets and drank the last of the water—no small feat with only one-and-a-bit lips, believe me. I then dressed myself in all my clothes and sat on my foam mat. My mind wandered back to Dave—what if he took too long getting back to the hut? I had a prime view of the front that was coming in from the west, it was like watching a freight train pull slowly across its heavenly tracks. A storm in the open at this height would be lethal. I assembled my shovel and awkwardly began to dig a hole for shelter. It was painful, slow work, but after two hours I had a shelter of sorts.

The hours drifted by. I sat there silently and motionless; all I could do to try and keep myself warm was to move my forearms and hands. After an hour or so this got a little monotonous so I just let my mind wander. I thought of Dave and how he was going. Surely he’d be at the hut by now, it had been five hours since we’d hit the deck. I tried not to think about the situation negatively, and soon began to philosophise about the workings of the world. For some reason, I never really considered myself in mortal danger. Sitting in the dwindling sunlight and growing cold was quite peaceful and beautiful. The reason I had come was laid out in the view in front of me—mountain upon mountain silhouetting the Tasman Sea. If my camera hadn’t been smashed into oblivion during the fall, I would have taken at least a roll of film.

I alternated between contemplating the scenery and wondering where the hell the chopper was. Then I noticed a black dot at the bottom of the ridge, in front of the hut—it wasn’t moving but I hadn’t noticed it before. I examined it for ten minutes but it didn’t move—maybe it wasn’t Dave after all. When I looked again I thought it had moved and over the next 20 minutes the dot made its way round the ridge. Only ten minutes to the hut, and the radio inside. I was ecstatic. All I had to do was sit and wait.

Half an hour passed and there was still no sign of a rescue attempt. Then I heard the familiar whump, whump, whump of a chopper far away. It appeared from the north though, which was the wrong direction. It came closer and closer, strafing back and forward and then heading straight for me. I felt butterflies in my stomach as I began to make out details of the chopper. Around 80 metres away it paused for a moment or two, turned, paused again and then headed down the glacier away from me. What the hell was going on? This front was growing in size and gaining fast. The sun had gone and the wind was picking up. If it took any longer than an hour I’d be screwed.

I sat there, nervously awaiting my rescuers. After another 20 minutes I could hear another chopper, this time from the south—surely they were going to get me out of there. It zeroed in on me with pinpoint accuracy, levelling out and slowing as it drew closer. Faces appeared behind the glass. It circled round 90 degrees, parallel to the ridge of Mt Cook. The door swung open and somebody appeared out of the side and waved at me to lie down. I had secured all of my gear when the first helicopter came to prevent it blowing away. I lay back and covered my eyes. Where I had landed was not flat but, with Dave’s help, I had dragged myself into the sun on the edge of the bergschrund. The pilot could not land here or anywhere on the side of the mountain but he would be able to get very close. He came closer and closer, eventually hovering about 15 centimetres off the snow. The man in the chopper motioned for me to get in. All I could do was raise an arm and sit up. Someone eventually jumped out and lifted me while my arms were given a forceful but controlled tug from inside. I was on.

The man, Andy, explained to me that the front was moving faster than they had first thought. The winds were getting too dangerous for the chopper to stay here—we had to go now. I could hear in the pilot’s voice that he was a little nervous. We pulled gently away from the side of the mountain before dropping down to a few hundred metres above the Hooker Glacier and then down the Hooker itself. Occasionally we lurched unexpectedly due to the wind, but I didn’t care. I felt so incredibly grateful to Andy and my other two rescuers.

Mt Cook Village appeared before long. We stopped and I was carried off the chopper. My right leg had stopped working altogether by this stage, it was a limp, dangling mess. A nice woman called Julie tended to me for a few minutes before there was a moment of commotion and someone appeared at the door wearing Dave’s clothes. Dave looked horrible. His left shoulder hung awkwardly forward, cradled about his diaphragm, and his hand was limp. He shuffled in incredibly slowly, taking steps no bigger than a few centimetres at a time. His neck was stiff and rigid, supporting a head I didn’t recognise. His face was swollen beyond belief—his cheeks, chin and lips bulged outward, forcing his mouth to pucker and stay open. His forehead and upper cheeks had pushed skin over his eyes to the point where he couldn’t see. Dave was effectively blind.

We were hooked up to monitors and Dave was put in a brace. He was guided onto his bed and I reached out a hand and grabbed his. It was all over. We were safe, alive and warming up. As the rain began to fall outside and the wind grew stronger it dawned on us just how close we had come to being stuck out there. I mentioned our luck to Dave but he was retching into a bucket. In ten minutes he was asleep.

Two ambulances, 200 kilometres, a few stitches, two days in hospital and a whole lot of pills and scans later we found out what was wrong with us. Dave’s spine was bruised badly, and it would take some weeks for the stiffness and pain to disappear. We had both managed to break our noses. Dave’s left shoulder had some soft-tissue damage and severe bruising and he had whiplash. I had managed to tear several muscles completely out of my leg and had an internal hole big enough to fit a hand into in my abdominal muscles. My hip was riddled with cartilage damage and, luckily, a smaller than expected amount of soft-tissue damage. My left ankle was smashed to smithereens; broken bone, ligaments and a plethora of torn tendons floated around inside.

Later that week we sat in a Youth Hostel in Timaru talking about the accident. Dave explained what had happened after he left me. From where we had landed Dave had made his way down and across the Upper Empress Shelf. This part had been reasonably easy although there was the chance of an avalanche. After that there had been a near-vertical wall of rock and ice. Dave had passed out at the top of this ice-field. He was woken by a spindrift avalanche and promptly vomited in the snow. He realised he had passed out while setting up an abseil anchor, so finished it off and abseiled down the wall to the edge of a crevasse. The particular crevasse was one we had crossed earlier by belaying ourselves down into it and then up the other side. Had Dave failed successfully to cross it he would have fallen 40 metres or so to an almost certain death. In the end, he found the narrowest part (still the best part of a metre or more wide) and took a running jump. He employed the same technique with two other crevasses before he had cleared the ice-field. It was then a slow plod to the hut. Although a fit person would have done this plod in no more than 15 minutes, Dave passed out halfway there, eventually taking more than half an hour. He described the descent as the most terrifying thing he had ever done and rightfully so; no mountaineer in his or her right mind would have wanted to solo those 800 metres.

More than a year after the accident Dave and I have almost recovered. Several months of physio and Dave was climbing again. I have now undergone surgery and a year of physio and went bouldering for the first time 11 months after the accident. We have both vowed to go back—I would like to do the Porter Col route again, but Dave wants something a little harder. Either way, we will climb Mt Cook together again.

Once again, I thank our rescuers. I also thank Dave—without these people, I would almost certainly not be here to write this article.

Other articles that may interest you:

Why Climbing Helmets Matter and How They Can Save Your Life

Rock Climbing Rescue on Tiger Wall, Arapiles and Near Miss on Balls Pyramid

Finding my feet, after a break | Macciza Macpherson

This article was originally published in Rock Magazine in 2004. The information, route descriptions, and access details reflect the conditions and ethics of that time. Climbing areas and their access arrangements may have changed significantly since then. Please consult up-to-date local sources, land managers, or climbing access organisations before visiting any of the locations mentioned.