Malcolm Matheson

First published in Rock Magazine in 1990, this feature introduces readers to Malcolm “HB” Matheson at a pivotal moment in Australian climbing. HB was an understated force quietly reshaping the standards at Arapiles, the Grampians and beyond. This article steps back into that era—capturing the grit, ingenuity and unlikely humility of a climber who helped redefine what Australian climbing could be.

This article was originally published in Rock Magazine in 1990. The information, route descriptions, and access details reflect the conditions and ethics of that time. Climbing areas and their access arrangements may have changed significantly since then. Please consult up-to-date local sources, land managers, or climbing access organisations before visiting any of the locations mentioned.

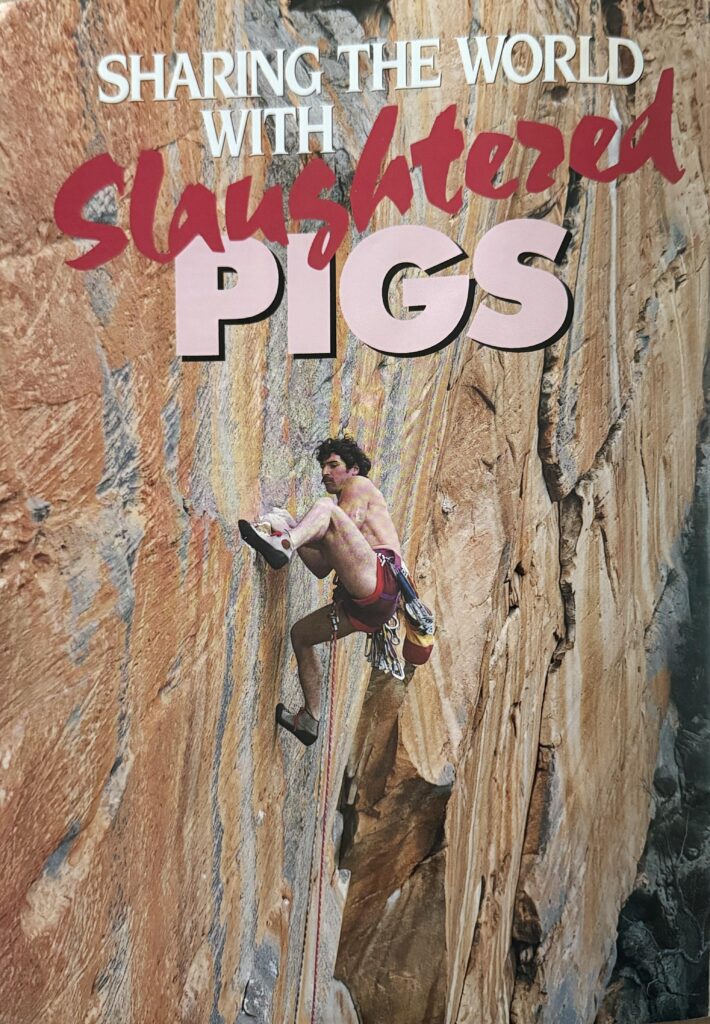

Originally Titled: Sharing the World with Slaughtered Pigs

Malcolm Matheson: not just another carcass in the meat market, if Glenn Robbins is to be believed.

A following the departure of yesteryear’s heroes for foreign shores in search of lucrative contracts, climbing in this country-so we are led to believe-has displayed all the direction of a headless chicken. This pathetic verdict is a savage blow to many competent and devoted climbers, who still dream of a day when recognition will come to liberate them from the overcrowded obscurity of the battery farm. A preoccupation with climbing performance at the expense of marketing skill has much to do with this relative obscurity. So in the name of justice and on behalf of those who are unaffected by the urge to hero-worship, I feel compelled to outline the rise of a relative unknown who has become one of the driving forces in Australian climbing.

Malcolm Matheson, widely known by the masses as HB, achieved notoriety in the early 1980s more for his prowess as an engineer than for his climbing ability. Malcolm produced limited quantities of technical climbing equipment so advanced and precise in design, so immaculately hand-built, and yet so modestly priced, that climbers throughout the world became delirious with desire at the mere sight of these glistening pieces of titanium; particularly the thin-crack specialists for whom these camming devices were designed. Demand exceeded rate of supply to such an extent that persons noticed to be in possession of these items would find themselves besieged by punters who would offer anything, absolutely anything, in exchange for HB’s titanium, and would have to be beaten off with a big stick.

Sadly, however, Malcolm became entangled in the barbed wire of bureaucracy. The suspicion accorded locally to most things not directly connected with wheat, sheep or hay-baling, combined with the immensely laborious production procedure required to gain little or no return on investment, administered the final, crippling blow to the manufacture of titanium equipment. Yet another glowing example of the dwindling support for Australia’s enterprising youngsters, and a most regrettable situation for all concerned. Malcolm’s manufacturing skills had not always been geared towards the production of climbing equipment. In earlier days, a rather handsome, high-powered Newtonian reflector telescope made largely of PVC piping, along with various instruments of bodily torture (weightlifting apparatus) provided many hours of blissful gazing and pain of blood-curdling intensity, respectively.

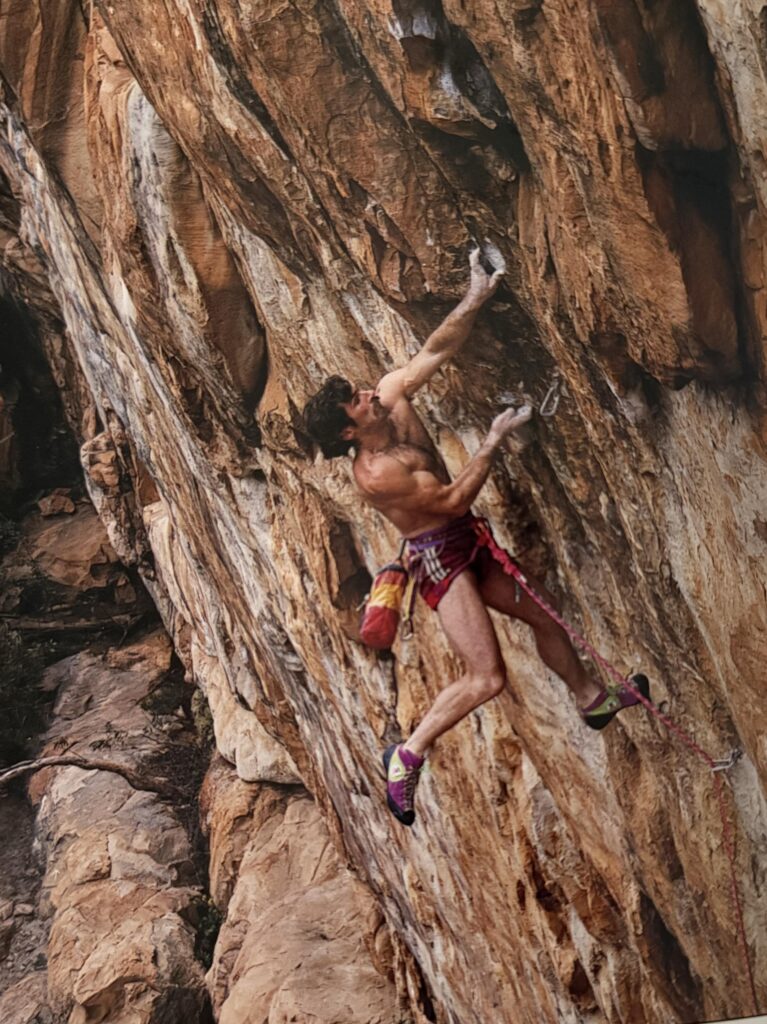

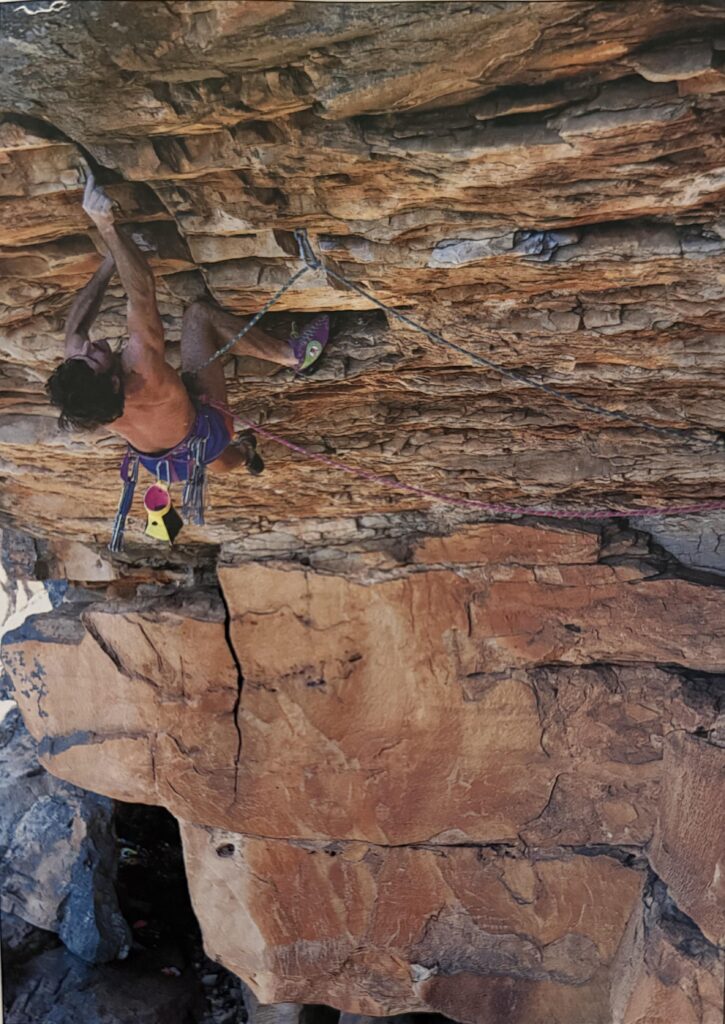

While in his early, inquisitive teenage years, Malcolm’s interest in power and energy encompassed chemical reactions of an unstable and rather explosive nature. It must be stressed that most teenage boys become obsessed either with booby traps, sharp implements or spectacular explosions at one time or another. Many a young brother or sister has been ensnared and tortured beyond all parallels to the Spanish inquisition as a direct result of an experimental stage Above, Malcolm Matheson doing what he does best-powering across roofs, this time that was afflicting an elder brother. Fortunately for his younger brother, this period of Malcolm’s life was both short-lived and relatively harmless to all but himself. Having taken his life in his own hands with these experiments, Malcolm very nearly lost both life and limb following the untimely explosion of a metal canister containing highly volatile substances, which left his right arm and hand riddled with shrapnel and the second and third fingers of his right hand permanently disfigured to resemble fleshy hooks.

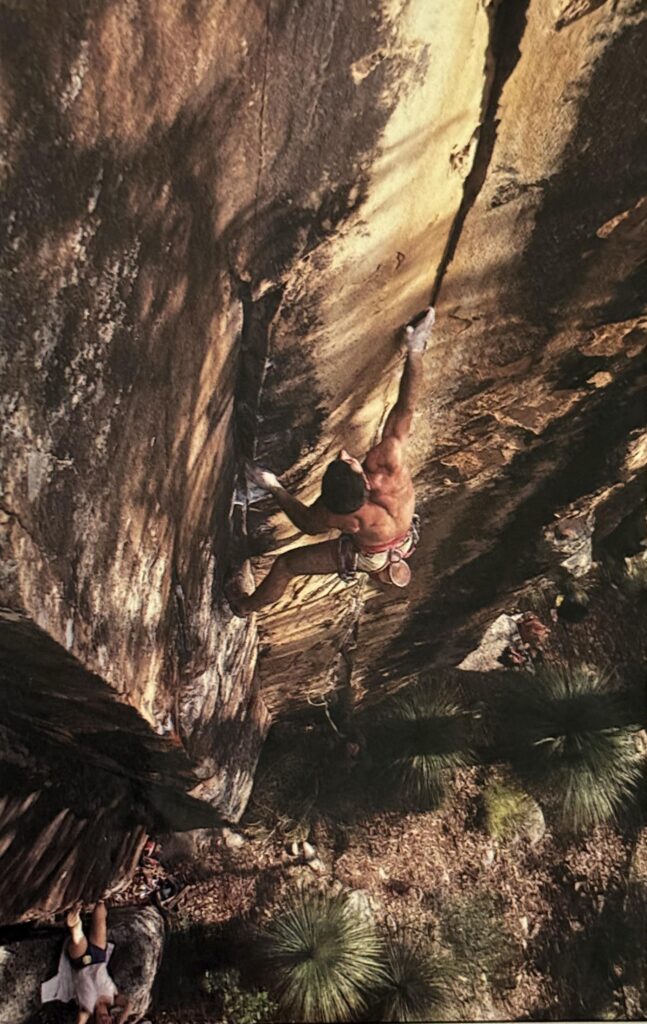

Left: Matheson showing signs of strain on the second ascent of the heinously strenuous David Or-Tiger (31), Mt Stapylton. Right: Matheson is no slouch on walls either; the first ascent of Sirocco (26), Taipan Wall, Mt Stapylton, All photos Glenn Robbins

Just recently, almost a decade after the infliction, surgeons located and removed an incredibly large fragment of metal from Malcolm’s biceps. After much struggling and slashing at the front of the muscle, the surgeons found it necessary to wade through a sinewy labyrinth from the side of the arm to retrieve the piece. Another fragment, detected by X-ray, will have to remain floating about in his hand until such time as it presents a problem. His fingers were diagnosed by specialists many years ago as being permanently and irreversibly kinked. Not one to be

discouraged by this grim prediction, Malcolm set about straightening his fingers by mechanical ingenuity and the only means available to him, the vice. Repeated attempts at tightening the vice about his fingers yielded little more than intolerable pain and the basis for climbing mythology, which has likened Malcolm to the Schwarzenegger creation, ‘the Terminator All mythological and legendary comparisons aside, Malcolm commands great respect in the limited society of climbers and associated hangers-on (myself included), where the air at times darkens with the sharpened blades of climbers hell-bent on obtaining immortality. Malcolm retains a reserved air, very much the opposite of what we have come to expect from our leading climbers. It’s just not natural. This quiet, unobtrusive disposition can only be attributed to his lifelong residence in country Victoria, where people are often so laid back that one must check to establish whether they are still breathing.

His non-consumption of alcohol or drugs and his non-participation in bizarre sexual practices have a tendency to unnerve the climbing élite. These people are to be found huddling in small groups, strange figures gesticulating wildly as they lunge about the dingy back bar-rooms of local climbing pubs, recounting the day’s flailings with a mixture of slanders and scathing half-truths. Questions like ‘How can this HB person expect to get anywhere in climbing, let alone life, without at least one of the social crutches we all rely on these days?’ or ‘Surely he must wake screaming in the night, tormented by visions of reality?’ are tossed about in less-than-polite banter.

Accounts of this man’s beginnings in climbing are colourful and varied. All sorts of tall tales and true have been presented as sworn testimony, many based upon pure fantasy, self-promotion and fame through association. After several stabs at the carcass, I decided to obtain the gist directly from the horse’s mouth. Popular belief would have it that Malcolm was thrown like a sacrificial lamb to the zealot gods of rockclimbing at the tender and impressionable age of 17, and thus ‘created’ in their very image. Were this the case, Malcolm would now be climbing in total disregard of his creators’ teachings, with an attitude of disdain and loathing towards all things shaded and aided. His unshakable faith in clean climbing practices offends against the code of conduct virtually every modern rock athlete abides by: ‘the Oinkpoint’, a whole-hog, no-holds-barred siege of walls, using anything within arm’s reach in the shameless pursuit of height and glory. Sure, everybody pulls on a piece from time to time; like masturbation and bowel movements, it’s something that everyone does but no-one wants to talk about. Some of us, however, take up the practice as a profession. Malcolm’s earliest experiments with the vertical took place in 1979. This was the beginning of the golden age of Arapiles climbing but the scene was far from the madding crowds of Arapiles, on the small sandstone walls of McKenzie Creek quarry in the outlying regions of Horsham in western Victoria. Belayed by his father or younger brother Doug, Malcolm set out to teach himself the basic movements of rockclimbing with top-roped attempts on this little quarry’s every weakness. He handcrafted a nifty camming self-belay device to be used in later, roped, solo ascents. Having exhausted the quarry’s potential, and more than likely his two belayers, Malcolm was signed up for one of the Victorian Climbing Club’s instruction weekends at Mt Arapiles. His initial training on ‘the big stuff’ was in the capable hands of Chris Baxter, now Editor of Rock, and Peter Lindorff. With a firm grip on the rudiments of protection and rope-work, Malcolm embarked upon an arduous programme of transition from bumbly to proficient athlete. To Malcolm’s undying credit, he achieved this Herculean feat within the short though vigorous period of two and a half years. An unfailing, computer-like memory for lengthy sequences of moves, the required racks and their respective placements, natural talent, dedication and strength above and beyond the call of duty are all contributing factors to his success: the very qualities which are often only grudgingly accredited to young men with country backgrounds.

Malcolm lived at this time with his parents in Horsham, barely an hour’s drive from Mt Arapiles. This allowed him to boulder for hours after work each evening until seriously pumped, often staggering out of the boulders in total darkness to zoom home for cooked meals and other creature comforts.

Bouldering became his forte, his passion; and in time, having many of Arapiles’ harder boulder problems totally wired, provided the vehicle for a little harmless joke. The mischievous duo of Jon Muir and Mark Moorhead formed the idea of making Malcolm’s afternoon bouldering schedule just that little bit more entertaining.

Left: Malcolm Matheson doing what he does best – powering across roofs, this time on the first ascent of Hamster Roof (26) Mt Stapylton, Grampians Right: Matheson on an early ascent of the Frog Buttress Queensland, test piece, Brown Corduroy Trousers (28) Images by Glenn Robbins

Anticipating his arriving fully pumped at the Golden Streak boulder, one of Australia’s most grappled features, Jon and Mark had greased the holds of The Golden Streak with lashings of Vaseline, and then retired at a discreet distance to witness the coming unstuck of one young Malcolm Matheson. Appearing round the corner of the boulder in full rippling bulk,

with his upper body resembling a flesh-toned glad-bag full of hamsters, Malcolm sidled up to the offending problem. Straining to contain their squeals of excitement until they were blue in the face, Jon and Mark watched, first with bug-eyed expectancy and then with disbelief. Malcolm remained in company with the rock, confidently cranking through the finishing moves, seeming not to notice anything out of the ordinary. Accounts of the pair’s anguish and torment will no doubt become legendary.

Believing himself to be chronically weak, Malcolm has broadened his outlook on training to incorporate the spasmodic pumping of iron, fingerboard and weighty lumps of automobile. Malcolm’s car is his real source of deep and abiding passion, while the fingerboard, once proudly displayed in the living room of his present dwelling, stands as a worn memorial to the young, torn from climbing by their tendons. Malcolm’s weight-training programmes have now taken on such gruesome and frantic intensity as to require an assistant (the dungeon-master’s accomplice), who runs about changing weights and adjusting the racks and instruments of Malcolm’s self-inflicted torture.

Having come to terms with possessing fat little fingers and a body more appropriately built for bricklaying, and having become somewhat besotted with climbing, Malcolm could no longer withstand the urge to move into the Pines-Arapiles’ favoured campsite and the climbing community’s dumping ground for broken hearts and misfits and closer to the action. He found himself sharing a camp with the élite, his jeans and baseball cap looking quite out of

place against a backdrop of lurid Lycra, dyed hair and pseudo-punk garb. A starling amongst peacocks. All hell would break loose in the evenings, as Malcolm prepared his meals after a long day on the crags. The drugged lentil set looked on in fear while enormous chunks of vegetable matter were hurled from a great distance into the wok at the centre of the fire.

Unsuspecting possums, scuttling about in search of food scraps, were relocated in the same manner. In the mornings I cringed as these peacocks in all their finery scratched about in the dirt, strutting their stuff, vibrating wildly in what would appear to be an intricate mating dance, all to attract a belay mate for the day’s flailing and wailing. Poor Malcolm didn’t quite look the part, but he seemed quite content with just being there.

Until now, Malcolm’s own climbing attire can only be described as dull, his one and only extravagance being a pair of lurid green and pink ropes. Glamorous appearance is of no concern to Malcolm and is left to the flamboyant, anorexic weirdos; a pair of tattered shorts held together by chalk and cold sweat suffices at present. Recently, though, I have noticed him, running fat little fingers over objects of vibrant colour, keen-eyed with desire. Oh yes, one day in the very distant future I can see myself squeezing him into a pair of Lycra tights; both of us may well die in the process.

Climbing on the ugly side of vertical has become Malcolm’s speciality; oversized arms and brutal style his trademarks in this new age of Australian climbing. Whereas in America, over four consecutive trips he displayed an incredible talent for jamming his pork-sausage-like fingers into the tenuous seams and cracks of test pieces at Joshua Tree and Yosemite. In California, his spectacular ascents of Joshua Tree’s Acid Crack and Yosemite’s Hangdog Flier, Rostrum Roof, Cosmic Debris, Fish Crack and Crimson Cringe seemed to devastate the Americans, who tend to believe that they and only they are the masters of this style of climbing. The realization that someone could be so accomplished and yet so modest and affable seemed to leave them speechless; perhaps for the first time in their lives.

Returning to Australia with this remarkable ability to stuff obscene amounts of flesh into ridiculously small crevices, Malcolm hurled himself upon Victoria’s crags in a flurry of arms and legs. The dream of classic new routes at Arapiles had by now become a faded memory, driving him into the outlying Grampians Range. Walls of indescribable beauty lie therein and for years have remained the object of secret, unrequited longing.

Areas such as Mt Stapylton and its Taipan Wall, once climbed back in the days of aid, have been found to contain the crucial lines in the next chapter of Australian climbing. Nicaragua (grade 30), the first of these lines to fall, will also be remembered as the most significant, established at a grade never before climbed in Australia outside Arapiles. A severely overhanging seam on Sandinista Wall, Mt Stapylton, it was climbed with all natural protection-a rare quality in a climb of this difficulty. After a great deal of deliberation, Malcolm later added Contra Arms Pump, at the same grade, to the same wall. Just round the corner, on the steepest and most intimidating section of Taipan Wall, stands Serpentine (31), the highest point in, Australian climbing achievement. In establishing this route, Malcolm shattered yet another misconception: that Australian climbers must perpetually flounder at grade 30.

With the annual onset of winter’s gloom in the Grampians, found Malcolm packing his little camming devices and rocketing up the inland highways behind the wheel of his Torana-his pride and joy. Wide-eyed and numbed by Midnight Oil at a million decibels, he arrive at Jivaro, Queensland, named for its dense rainforest after a little-known head-hunting tribe of South America. Ferocious mosquitoes and gigantic skeletal spiders set a fearsome backdrop for one of Queensland’s hardest routes, Schwarzenegger (29).

Photographs will never do justice to this climb. The atmosphere of the cave whose roof it takes and the objective dangers-mosquitoes, wriggling beasties and stinging trees-give a sensation akin to horror. The climb lacks all aesthetic beauty, respite or positive holds; every facet of its grotesque ceiling slopes alarmingly.

The tactics employed to climb Schwarzenegger have something of the grotesque grace of sumo wrestling. After more than a decade of dedicated climbing and training, Malcolm has the strength and physique to match. Any butcher would be proud to have Malcolm’s upper body grace the meat rack in his cool room, sharing the world with slaughtered pigs. With a large percentage of Australia’s hardest routes to his credit, I cannot comprehend why the rewards and

recognition seemingly thrust upon past leaders in the field have been withheld beyond this man’s reach.

Over the last two years, some commercial support has come Malcolm’s way in the form of harnesses, ropes and hardware from an importer of climbing equipment. This is not to be interpreted as selling out to the powers of capitalism. For someone who has put as much into rockclimbing as Malcolm Matheson, we are talking survival.