How to deal with injuries as a rock climber

Coping with Injury

Words: Dr Kate Baecher

At some point most climbers will face an injury of some description… awkward falls, overtraining on the hangboard, or just tripping over at the crag. We’ve all been there and, frankly, it sucks. The desire to mope is high. However, the psychological component of recovery impacts not just how cranky we feel about the situation, but can ultimately influence physical recovery too. Clinical and Performance Psychologist Dr Kate Baecher examines why it’s so important to look after your mental health while your body heals from injury.

Imagine this for a moment… Climbing is your passion. You’re at the gym two or three times a week, and outdoors on the rock at every possible opportunity. Your computer browser history brings up climbing clip after clip after clip on YouTube. Your colleagues occasionally catch you staring into space and moving your arms in strange positions as you mentally rehearse a particular move. You’ve booked a holiday to Green Climber’s Home in Laos and it’s just four more weeks until you leave. Then…

BAM!

You hear a popping noise and feel a sharp pain in your finger as you pull on a crimp.

Your stomach drops. Your heart sinks. You’ve heard all the horror stories about tendons and pulleys and recovery time.

“It can’t be,” you think. “This happens to other people, not to me.”

It’s not just that you are injured and can’t do one of your favourite things. After all, a finger injury probably won’t stop you from performing the majority of your everyday tasks and functions. It’s the fact that being a climber is a large part of your identity. It’s probably also where you find friends and support. Moreover, for most climbers, climbing itself is a form of self-care and meditation.

Remove all of these, and the psychological impact is huge.

Research has shown that a significant physical injury can have a direct correlation to the development of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress. In fact, if the appropriate psychological support is not put in place early, recovery and healing time can be exacerbated due to the complex interplay between physical and psychological factors.

So what can we do to support our minds whilst our bodies are on the mend?

Grieve

Grief is a normal and healthy psychological response to loss, and an injury = loss. This loss can have many dimensions: loss of a goal, loss of capability to engage in activities that you love, loss of routine, loss of identity, and loss of the future which you’d envisioned. But here’s the thing, if you don’t grieve, you won’t process the loss, and if you don’t process the loss, you won’t move through it to a stage of acceptance during which you can start to heal.

So, allow yourself to grieve. Grief is rarely pretty, and it’s also uncomfortable. But allow yourself the space to grieve properly. And then after that? Change lanes.

Don’t slow down. Change lanes.

Accept that you are injured, but know that you don’t have to stop engaging in everything climbing-related. In fact, it’s better that you don’t. I’m not here to talk about the physical rehab (speak to the appropriate medical profession for that), but there are a few things you can do psychologically which will lessen the grief and keep you around the environment that you love, even if you have to modify what you do there.

Consider doing your physical rehab at the climbing gym, or at the same time as you’d normally climb with your mates. You might be able to belay them, you might just be a cheerleader for them. Regardless you’ll enjoy the same level of banter, beta and shared frustrations that have become part of your day-to-day life. Yes, it will be hard at first, but remaining part of your climbing crew will do wonders for your mental health AND it will force you to get out of the house, and hopefully out of your head, for a few hours a week.

Understand the difference between ‘patience’ and ‘waiting’

Often when we are injured and unable to climb in the manner that we are accustomed to, it can feel like we are simply waiting until the injury heals. Like, it’s the injury that dictates its trajectory, healing and pathways. This is only true to a small degree. If you approach your recovery with patience, you will be able to better cope with the time frames and probable false starts. Patience doesn’t mean doing nothing; it means focusing elsewhere. Maybe this is the time to develop breathwork practices, or practice slack-lining, or build up your cardio. Maybe it would be a great time to delve into reading and research (about climbing, of course). Maybe it’s time to focus on mental skills, mental rehearsal, and mindfulness.

Locus of control

As an aside, the biggest delineation between patience and waiting, lies in what we call the “locus of control”. Every person has either an internal or external locus of control. Those who demonstrate an extrinsic locus of control are more likely to attribute the injury/blame to external factors like the condition of the climb, or the belayer, or the weather conditions. Those who demonstrate an internal locus of control are more likely to look within and explore the ways in which they have contributed to their own injury. Maybe it’s because their stress levels were high and they didn’t warm up properly. Maybe it’s because they were distracted and their mind was elsewhere. What we do know about locus of control is that the version you exhibit not only has a significant impact on how you view the world, but it also has a correlation between success, coping, self-control and goal-attainment.

If you approach your recovery with an intrinsic locus of control, it means that you believe that you have a direct influence on your recovery trajectory. You believe that if you do the work, you’ll reap the benefits. And so you do do the work, and you do reap the benefits. But if your recovery is up to your physio and trainer, and you only do the work during those appointments, it is likely that your recovery will stagnate.

Dealing with unknowns and uncertainty

One of the best ways to counter the horrid feelings of facing unknowns and uncertainties is not to ignore them. Rather, write out a list of all of your worries about your injury and recovery process. By acknowledging them, not only are you respecting them and validating them, but you are honouring yourself. Those fears, insecurities and uncertainties need to be acknowledged, because then you can manage them.

Once you’ve written your list of worries and concerns, ask yourself for each one, “Can I control this?”

If yes, then develop a plan of action. If you can’t control it, ask yourself, “Can I influence this?”

If yes, then you can also write an actions list but keep in mind that you can only influence the outcome, not control it.

And lastly, ask yourself, “Can I have any impact on this whatsoever?” If the answer is “no”, then you need to direct your energies into the factors that you can influence and control.

Be adaptable

There will be unexpected factors that impact your recovery trajectory. Stay adaptable and know that starting again (and again, and again) is okay. Frustrating, but completely okay.

Looking after yourself while you’re injured

Climbing is a huge part of our lives, including our wellbeing and our mindset. When we don’t have our usual access to that, the other components of our health can take a hit. If this occurs, be understanding and compassionate to yourself. Then, get up and start again. Slowly. Focus on your diet, (appropriate and gentle) exercise and sleep patterns. Talk to your mates, or even a professional. When you do get back to climbing, it will be hard, demoralising and slow. You’ll be maxing out on grades that you used to warm up on. You’ll be comparing yourself to your climbing mates who aren’t injured and haven’t had months off, so maybe you’ll probably feel pretty low for a bit. But remind yourself that a slower and more consolidated holistic recovery will be a stronger recovery, and will be less likely to cause secondary injuries.

Stress has a direct correlation to the likelihood of injury

Evidence shows that the way that we manage stressors is related to injury risk. That is, someone who has personality characteristics such as high anxiety, is experiencing high life stress, and has insufficient coping resources, is more likely to be overwhelmed by everyday stressors and react with maladaptive responses that increase their susceptibility to injury. This stress-injury relationship is at the heart of sport injury psychology and does not just impact the likelihood of getting injured, but also the trajectory of recovery from injury. Ultimately if you can address the stressors in your life, you’re less likely to be injured in the first place and you’re more likely to recover faster from injury if it does happen.

Injury in climbing is hard and returning from injury is harder still. Allow yourself to grieve, be kind to yourself, surround yourself with good people. And go slow.

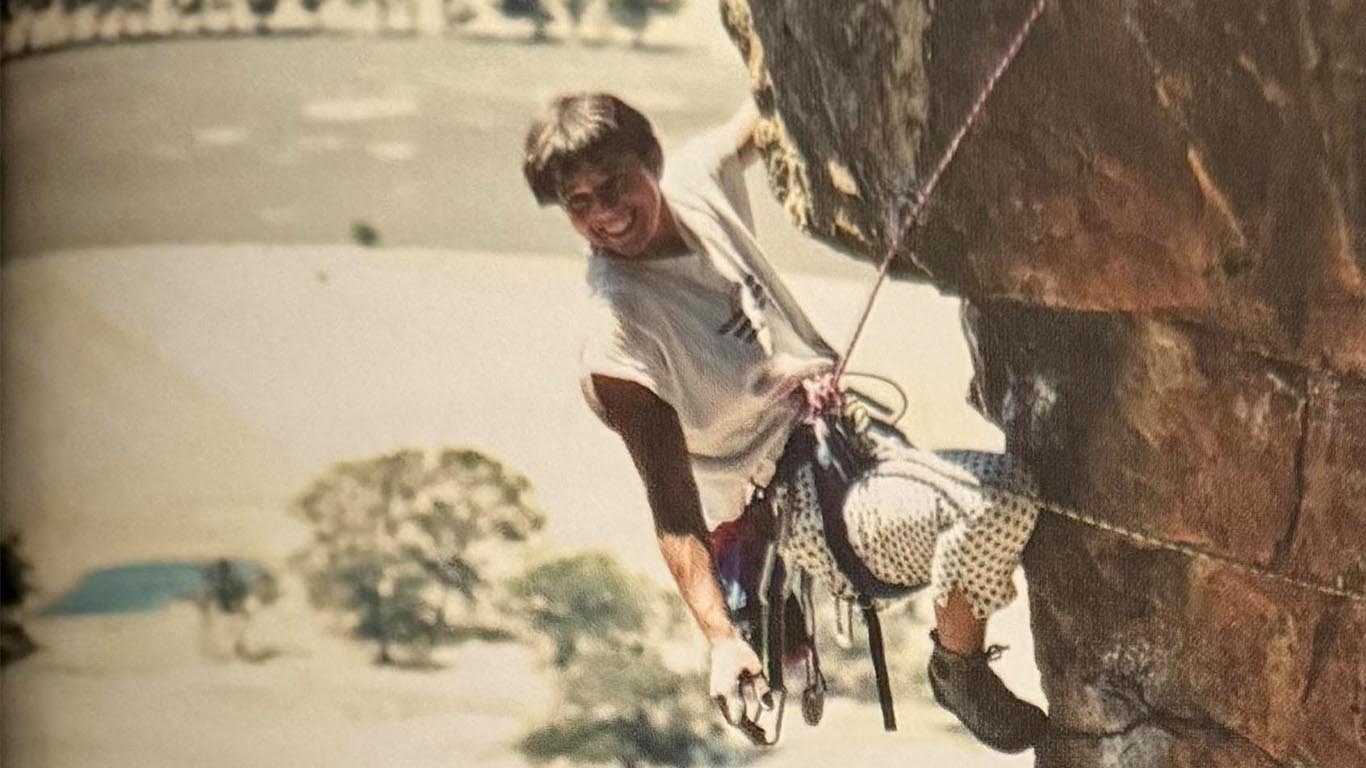

The incredible Rose Weller sending iconic Nowra line, White Ladder (33). Image by Michael Blowers.