Getting to know rock climber Sarah Larcombe

(This story originally featured in Vertical Life #47)

Words: Dave Barnes

Photos by: Caitlin Schokker

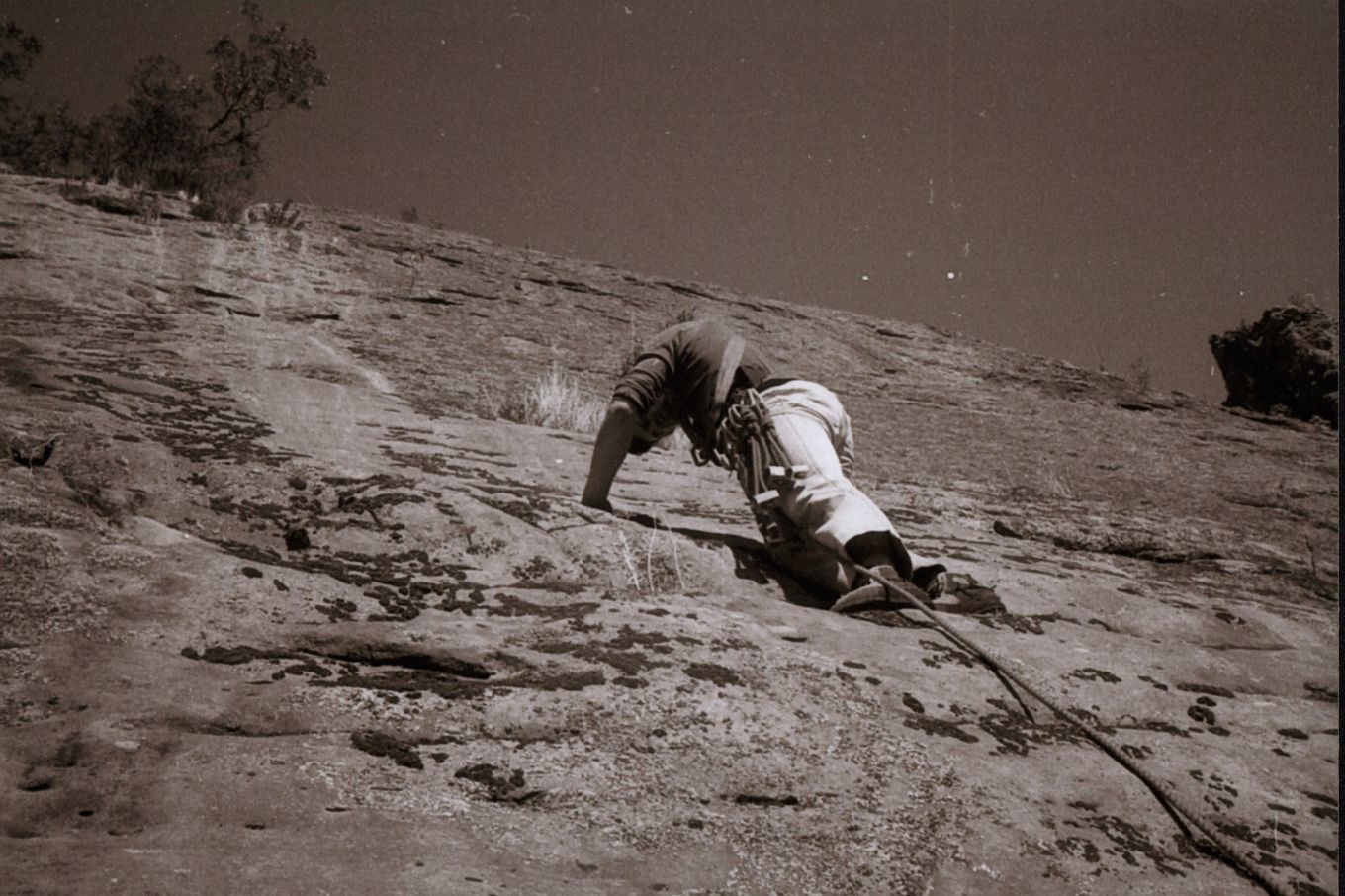

I remember as a kid flagging to reach what otherwise seemed impossible. Flagging is an aesthetic climbing technique that feels more like dancing. Watching Sarah Larcombe climb was just one long flag and each of her sequences up the wall had her able leg counterbalance her prosthesis. She just flowed; she was dancing.

A cool breeze fought with the sunshine. It was a typical early-summer day in Tasmania. I was to meet Sarah Larcombe at a designated street on the outskirts of Hobart. Right on time she arrived with a photographer in tow. She had the traits of a climber, but not hard edged in any way. Making our introductions we headed to Genesis, a crag near Hobart I had been developing. Here I would find the spine for a feature on Sarah, and she would get a taste of Tassie climbing. We would both be in for a surprise.

The track was uneven, and I watched Sarah seeking foot placements between stubs of rock. While I walked like a drunken sailor, Sarah was deliberate. Sarah was born with Femur Fibula Ulna Syndrome, in brief, combinations of congenital anomalies in the bones of the thigh, lower leg and forearm. For Sarah it was limited to her right leg; she was born with a shortened femur, a club foot, and without a fibula. These could not be corrected and were not compatible with walking, so her leg was amputated at nine months of age. Sarah doesn’t dwell on it, that’s all she’s ever known.

On the walk-in she just worked through whatever obstacles impeded her and didn’t stop talking while she did.

“Accessibility hinders disabled climbers, especially in the outdoors. And there isn’t much effort being put into improving physical access to climbing areas in Australia,”

she explained. “It means most of them are off limits to a lot of adaptive climbers. I don’t expect all climbing areas to be fully accessible, but things could be a lot better than they are.”

On arrival at the cliff top, the photographer and I got organised while Sarah began sorting her gear. I noticed her titanium prosthesis. I wondered how she had adapted her technique to make use of the shiny stuff, and I was soon to find out.

The rap in was uneventful for me, but Sarah quickly noticed this was no Arapiles. Sea cliff climbing on Alumn rock is a juggling act of fragile holds and choss, while the ocean distracts you from below. After the precarious rap in, I was stoked that no rocks had hit her. At the base, gear sorted, I led off on Raiders of the Lost Faark (19) to give Sarah her first exposure to choss climbing. Sarah looked at me with raised eyebrows and a smirk. I could see her mind instantly compute how she’d nail the route.

It’s not just in climbing where Sarah’s smarts are obvious. Sarah has a PhD in infectious diseases. She moved to a research support role in 2022 in an attempt to find a job that better suited her training and travelling for climbing. It hasn’t been a straightforward solution though.

“I’m trying to figure out what I should be doing, and trying to find a better balance between work and climbing,” she explained.

Before our day out I had asked her mum for some background on Sarah. She didn’t talk about Sarah accomplishments though; her focus was on her daughter’s attitude.

“Sarah has never shied away from hard work. Sarah aims high in everything she does and rises above her circumstances achieving things that I could have only dreamed of as a mother,” she said.

Sarah adjusted her prosthesis, slipped a boot onto its metal and her other show onto her foot. Standing there she looked every bit the climber; limbs made for reach, torso ripped. And that star factor; her hair was perfect, her clothes were pristine against the dirt and choss, and her focus was sharp. I felt drab in comparison.

As she chalked up with her eyes computing the route, I asked her how she first happened upon climbing. Her story was much like your own.

“My first climbing experience, outside of maybe a school excursion or birthday party as a kid, was at La Roca Boulders in 2019. I went with my friend Jess—we were both doing our PhDs in neighbouring labs at Monash Uni,” Sarah said. “We’d talked about trying climbing and heard that there was a bouldering gym 10 minutes from campus, so we didn’t have any excuses left not to try it!”

Sarah remembers being nervous. She read the whole safety waiver because she was worried it would say something that meant she wouldn’t be able to climb because of her disability. It didn’t. That first session was an awakening.

“I wasn’t fit or strong at all, but climbing is fun even when you’re falling off things,” she said.

It was a good start and she and Jess began bouldering once or twice a week. After about a month Sarah splurged on her first pair of climbing shoes. Unfortunately in her first session wearing her new shoes, she fell and broke her left ankle. But, in her usual style, it didn’t hold her back for long.

At Genesis, Sarah cruised the first third of the climb. Each move was deliberate. I watch her legs work the climb.

Foot placement for Sarah is essential as she needs to sort a balance between flesh and steel. A royal kind of flagging.

Between climbs we chatted about the technicalities of being a climber with a prosthesis.

“Unlike a lot of amputee climbers, I actually just use my walking leg for climbing,” Sarah explained.

“Most others either use a leg with a specific climbing foot, which tends to be short and stiff, or they don’t climb with a prosthesis at all. So, there’s not a lot that goes into it for me, other than putting a climbing shoe on my prosthetic foot, which is a bit tricky.”

Sarah’s disability doesn’t weigh on her—remember, she’s had this all of her life, it’s a part of her. What her body may find difficult, her resolve overcomes.

“I’m probably a bit of an overachiever, and maybe I’m subconsciously trying to subvert people’s expectations of who I should be and what I’m capable of,” Sarah said. “I grew up poor and I became the first person in my family to go to university, and I ended up with a PhD. I was born disabled, and I became a rock climber.”

Watching this young woman climb, it was apparent she was a thinking climber, and that her academic brain has transferred into measuring movement. She does not wing any move; all progress is measured as she pauses, paying particular emphasis on foot placements and pre-empting where that will leave her right leg in anticipation of the next move.

Sarah explained,

“Climbing has given me a new perspective on my body, because when I’m on the wall I’m able to do things that seem impossible on the ground.

It’s a freeing feeling, and I love the creativity of movement in climbing.”

It’s a feeling she helped introduce others to as well when she recently took a group of paraclimbers on a trip to the climbing Mecca of Arapiles.

“It was really special,” Sarah said. “For some of them it was their first time climbing outdoors, so I was really stoked to be able to introduce them to it in such an amazing place. I’m excited to see more paraclimbers in Australia getting outdoors!”

Watching her climbing I could hear in her voice and see in her body an enjoyment of problem solving. Her calm approach and thoughtfulness had her cruise the crux, clip the ring, and chat to us below about microbiology and if she brought the correct [prosthesis] leg or not.

Since that first day at the bouldering gym, Sarah has made significant leaps forward with her climbing and is a competitive climber of standing competing in every IFSC international paraclimbing competition since 2022, podiuming in each. In total, she has achieved a World Cup gold, five World Cup silver, and one World Championships silver. Her first medal (World Cup gold at Salt Lake City, 2022) was Australia’s first ever IFSC World Cup medal. She now wants to add some outdoor accomplishments to that list.

The World Champs in 2023 was the largest field she had competed in, and it was the last competition of the season after three World Cups.

“I’m glad that I managed to put in a decent performance and stayed consistent throughout the whole season. Very consistent—I came second in every IFSC competition that year,” Sarah said.

“It looks good enough on paper, but I’d like to do better this year.”

This is the signature of an athlete; You’re only as good as your next performance. The trick is believing that you can. There are a few others who believe in Sarah too. The North Face, Scarpa, Climbing Anchors, and Integral (via Wattlenest), have invested in Sarah with sponsorship and support—and she would not be able to keep smashing milestones without it.

“It takes some of the stress off my shoulders knowing I have a bit of money set aside to travel for competitions, and I’m covered for a lot of my gear needs,” she explained.

Carlie LeBreton is an accomplished route setter who got to know Sarah through the competition circuit.

“In my position it’s been great to see Sarah’s progression in helping Australia become a force in paraclimbing,” Carlie said. “I’m excited to see her apply her skills to climbing outside as she broadens her abilities and expands her adventures.”

Sarah’s sponsorships don’t cover everything, so she still works to be able to afford her training and travel costs. Being busy and tired from the workload means she feels she can’t give 100 percent to anything.

Whilst roping up for her next climb she said, “I’d really like to find a way this year to reduce my work to part time so I can make climbing—and my climbing work like my board/committee positions with ACV [Adaptive Climbing Victoria], SCA [Sport Climbing Australia], advocacy, etcetera—more of a priority.”

We moved onto our next climb; Sarah negotiated Edge of Eve (19) onsight. A committing climb navigating an arete high above the water. On some moves she could not see her feet, which made her slow as she sought solid placements, a challenge for any climber at Genesis.

With her cheeky grin she later commented that climbing there was one of her more memorable experiences. “That was my first time climbing on sea cliffs with loose rock, and I wasn’t totally prepared, but it was equal parts fun and scary,” she said.

On the way out of the crag we chatted about new routing and the pleasure of discovering new places. She spoke about her current goals of getting out more, accompanying other adaptive climbers outdoors and, of course, continuing to improve her climbing.

She spoke about wanting to use her profile to make outdoor climbing more accessible and to inspire people to look beyond any preconceived notions of what people with a disability are capable of.

Back at the vehicles we said our goodbyes and as I watched Sarah speed off—she was now late for a sponsor’s event—and I couldn’t be anything but impressed with her energy, her climbing, and her focus on advocacy and community. I have no doubt that if anyone can increase the visibility and accessibility of adaptive climbing, Sarah can.